Chaalchitra Ekhon - An Apt Tribute To Mrinal Sen

The film is Anjan Dutt’s centenary tribute to his mentor

“Script, direction, gimmicks, that is Kunal Sen,” this was said by Kunal Sen portraying director Mrinal Sen (Anjan Dutt) during an interview in a scene of ‘Chaalchitra Ekhon (Kaleidoscope Now)’. The film is Dutt’s centenary tribute to his mentor, friend and guide Mrinal Sen.

This is not a remake or a contemporary version of Mrinal Sen’s original film ‘Chaalchitra (Kaleidoscope)’ released in 1981. It is a cinematic journey through Dutt nostalgia. He had begun his career in films as the protagonist in Sen’s original version of this film.

This film is an incredibly brilliant tribute to Sen as we knew him – totally unpredictable, erratic, irrational and eccentric. Yet warm and friendly.

The film is a faithful representation of these very qualities of the great director whose easy accessibility to all, keeps him alive in the memory of all those who knew him over a span of time.

Director-actor Dutt who is also a lyricist, a noted singer, and actor reveals his remarkable memory of his debut film ‘Chaalchitra’. More than marking his debut as an actor at a critical period of his life, Dutt’s work in the film which brought him in contact with a director he failed to make sense of, changed the map of the rest of his life.

He made his debut in the film during a phase of depression, when his life was going nowhere, his theatre group had broken down and his wife silently bore the financial burden of his family with a young child to take care of.

He hated Calcutta, and was preparing to take up a job in theatre in Berlin. So, he was more shocked than surprised when ‘Kunal Sen’, as he is named in the film, asked him to be the protagonist of his film ‘Chaalchitro’.

This placed the young man with large eyes in the horns of a dilemma. He discovered that he had to act in a film which had neither script, nor dialogue and where the director followed his actors with his cameraman anywhere in the city, from inside a car with the director seated in the window, or, seated in the open dickey of a car while Ranjan (Saaon Chakraborty) walked along the road, or took a ride in a tram car, or, to prepare himself for the job in Berlin.

Surprisingly, this young man, in spite of becoming the ‘discovery’ of a great director like Kunal Sen, is not happy with this new responsibility, and with a director he has nothing in common with, specially in terms of ideological and political convictions which are polar opposites of the ones his director is known for.

Mrinal Sen’s original film ‘Chaalchitra is about an unemployed but intelligent young man seeking a job as a journalist in a local paper. The editor gives him a hard deadline of producing a newsy but intimate story of his own middle-class milieu within two days.

He first tries to build a story around the smoke emitting from the earthen ovens used by the wives in his neighbourhood which disturbs the neighbours but there is no alternative. The editor does not find this interesting so he tries to look for another story.

He keeps on interviewing street beggars, a fake god man and others, finally zeroing on the slippery courtyard of the low middle-class housing complex he lives in with his mother. Every single day, one or another woman slips on the slippery compound but no one is interested in getting it cleaned.

Then, one fine day, all the younger members of the housing complex get together and begin to clean the compound of its mush. He thinks about this collective action and decides to go into action himself.

When I watched the original film a few years ago, I could never have imagined that the director Mrinal Sen made the film minus a script, written dialogue and a workable screenplay.

Dutt’s film gives us a wonderful insight into this strange manner of filmmaking by a whimsical director who smokes like a chimney, who says “Excellent” or “Cut” after almost every single shot while the actor remains either confused or angry with himself as much as with the director.

This pushes me to explore the idea of categorising both ‘Chaalchitra’ and its tribute ‘Chaalchitra Ekhon’ within what is known as ‘Third Cinema’.

What is “Third Cinema”? This offers a unique insight into a completely different way of filmmaking which few of us are familiar with. This was first propounded by the two Argentinian scholars Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino in their 1969 essay ‘Towards a Third Cinema’.

The essay tried to shed light on counter-hegemonic efforts created under hitherto unknown conceptions like “Imperfect Cinema”, “Guerilla Cinema” “Camera as Gun”, “Aesthetics of Hunger” and “Aesthetics of Liberation.”

Originating in the 1960s and 70s, in Latin America, Africa, and Asia, Third Cinema represents a departure from the mainstream (First Cinema) and auteurist (Second Cinema).

It focuses on films as tools for political and social change. It rejects commercial and entertainment objectives, emphasising collective, guerrilla-style filmmaking and themes of anti-colonialism, class struggle, and cultural identity.

If one were to look closely at Dutt’s nostalgic trip into the making of the original film, or, the original film which inspired this film, then it would be right to categorise these two films as ‘Third Cinema’.

One has no clue whether Dutt had a written script to work from as on screen, it comes across as an “imperfect” film-in-the-making whose director and technical team are not the least bothered about form, content, dialogue and even actors other than Sawon Chakraborty (who plays the original Anjan Dutt) who appears confused about his director, technical crew, the production manager’s (Subhashish Mukherjee in a brilliant cameo) passion about the distribution of food during lunch break during shoots and so on.

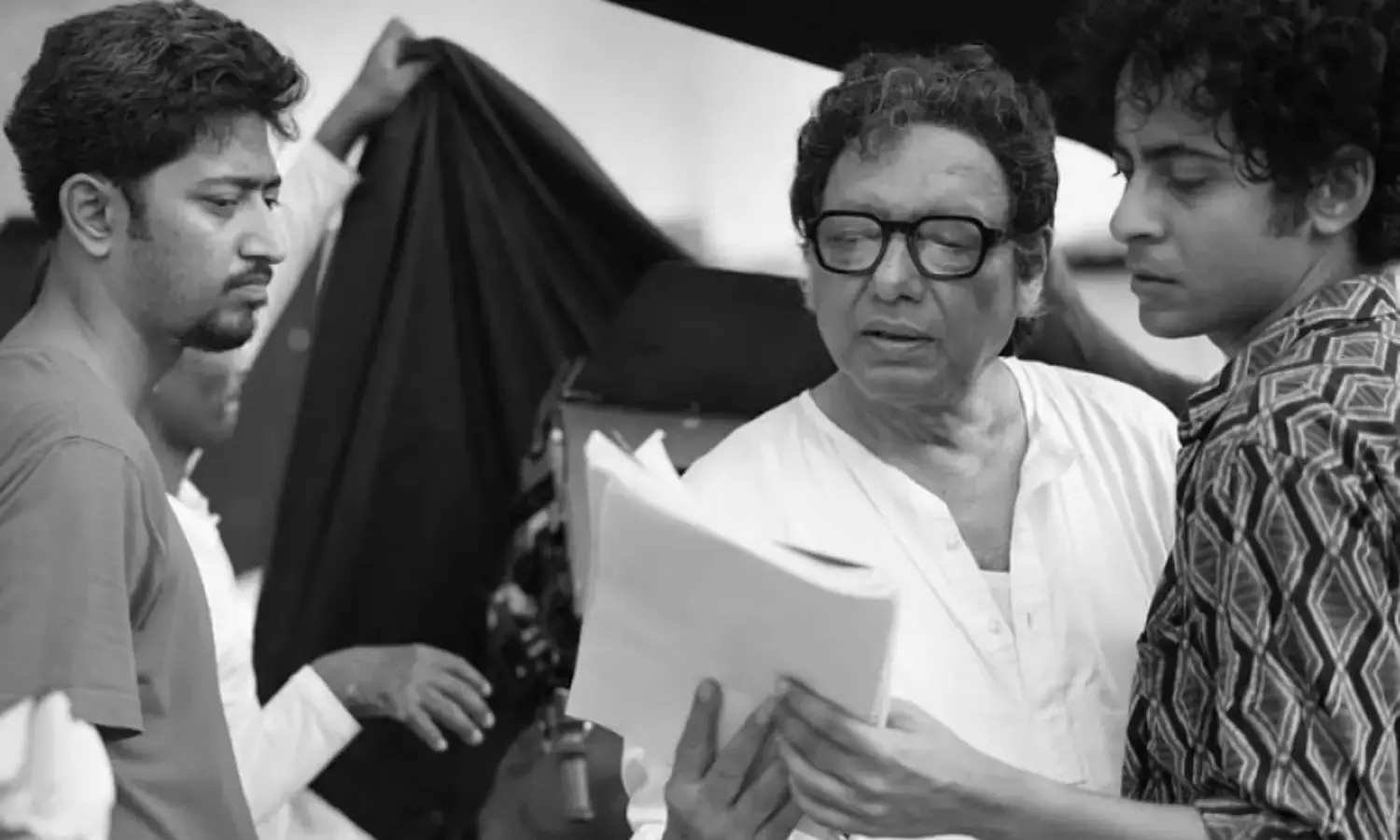

Dutt who plays Kunal Sen (Mrinal Sen), has taken extra care in getting across the minutest details about his 40 years of bonding with the director. This includes the wig which looks a bit put-on though, black-framed glasses, prosthetics on the face to make the character look as close as possible to the original Sen. Add to this the sparkling white pyjamas and kurtas that were his trademark.

The same goes for the director’s body language, seated on his arm chair with his feet flung out in front, his constant smoking with a cigarette dangling from his lips and last but never the least, the way he directs each scene with shouts of ‘cut it’ and ‘hochhena’ (not happening) and “excellent” in the most eccentric of ways never mind if his team goes bonkers over his eccentricity. But Dutt here is quite used to it.

This is Dutt’s most outstanding performance as an actor in a film, and that is saying something as he has always been a brilliant actor. Bidipta Chakraborty as his wife (Gita in real life) is convincing in a cameo while Suprobhat Das as the cameraman J. K. Madhavan (cinematography legend K. K. Mahajan) is shown not only enjoying his daily dose of you-know-what but also pushing the young Ranjan to follow suit.

The devotion and loyalty of Sen’s crew to their eccentric director has to be seen to be believed. Director Sekhar Das as Utpal Dutt in a single scene tells Sen to give the young boy a break and then, without waiting for Sen’s permission, shouts “lights off” just like that.

Chakraborty throws up a very expressive performance with his large eyes brimming over with tears, with anger, with frustration, with a sense of being rejected in his debut performance. One finds it strange that Ranjan Dutt’s wife has been sidetracked with a single scene and described in absentia by Ranjan.

The film is filled with beautiful moments you carry with you beyond the auditorium. In a scene shot inside a tram car in which Ranjan is commuting, which is being shot, the director tells him to chew the ticket and then swallow it! Ranjan swallows it at once with some difficulty.

Soon however, Sen forgets that he had asked the actor to swallow the ticket, turns around in the tramcar and asks him to throw it out! Someone points out that he had told Ranjan to swallow the ticket. Why? No one knows, including perhaps the director himself.

In one sequence, Ranjan takes the screenplay of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s ‘Oedipus Rex’ from Kunal Sen’s bookshelf, which the latter then signs and gives to Ranjan.

The generation gap between the two men – in terms of age, experience, theatrical ideology and political convictions are distanced as they should be, of course, to begin with. Ranjan, a ‘today’ generation young man believes in individualism and not collectivism.

He is deeply influenced by the works of Jean Paul Sartre, Peter Weiss and Bertolt Brecht while, though Sen does not say this in so many words, is a Marxist who, looking at his very grass rooted lifestyle, reveals this. In the end however, Ranjan chooses not to go to Berlin and to stay back in Calcutta which he has grown to love.

In another shot, while Sen is on the terrace of his flat, which happens quite often, a tearful Ranjan suddenly walks in from the door and comes and hugs him tightly. It is a touching scene especially because it is preceded by the young actor not quite happy with the way his director is presenting him and preparing him for his performance.

For him, the journey from intellectual theatre based on the life of Marquis de Sade to a film directed by an internationally renowned director he is not quite impressed with, brings out the actor-director relationship to the fore quite powerfully.

The film works out a fine balance with an imaginative yet realistic blend of form and content, of narrative and action and of dialogue and editing. The music (Neel Dutt) brings about a lyricism in this very non-musical film and blends into the narrative quite well as it is understated and subtle and positioned well.

The cinematography takes on with a dominance of yellows and browns, beiges and rusts perhaps to capture the “period” flavour of the original film. The production design of Sen’s home with a balcony that looks out to the traffic-filled streets below, the place where Ranjan is directing his theatre actors is both realistic and adds to the visual quality of the film, scaling down any glamour that might have stepped in. Mahajan’s understanding the vibes of his director is now a part of known history though he predeceased Sen by several years.

Sen is once quoted to have said, “The people must react. To be able to react in the most revolutionary manner is magnificent. Since the people are not allowed to choose between life and death, only by choosing death can they choose life.”

This marks an apt closure to this review of a great film on a great master, a greater human being, produced, directed and enacted by another great actor-singer-lyricist-filmmaker, Anjan Dutt. Kudos for a beautiful, and more importantly, unforgettable film.