Staging ‘Unpalatable Truths’

Chetana, a Kolkata based theatre group, is bringing Marathi theatre to the Bengali audience

The best part of contemporary theatre performances in the country is that theatre performers, directors, and playwrights have begun to bank on translated adaptations of plays originally written in a regional language. Instead of plays written in their respective mother tongues, or universal classics like works of William Shakespeare, theatre groups here are picking plays in Marathi, for example, and staging it in Bengali with their own interpretations, playing-around with the characters, plots and contemporary setting.

Chetana, a Kolkata based theatre group, was first formed in 1972 by Arun Mukhopdhyay in the heyday of group theatre. It is now trying to revive old hits of this group and also stage plays translated or adapted from other Indian languages to Bengali.

The group is also reviving its old plays like ‘Jagannath, Marich Sangbad’ and so on. The performances are electric, the sound-track imaginative, the beautiful music and outstanding set design is drawing full houses for each show.

The original play in Marathi titled ‘Sathecha Kay Karaycha’ (What is to be done with Sathe) was authored by the noted playwright Rajiv Naik. The title, translated in Bengali, is called ‘Opriyo Shotto’ meaning, ‘Unpalatable Truths’.

I think the Bengali theatre audience is watching a Rajeev Naik translation for the first time in Kolkata. Director Suman Mukhopadhyay, the elder son of Arun Mukhopadhyay, has directed the play while Ujjal Chatterjee has translated it in Bengali, possibly from the English translation done by Shanta Gokhale whose three English translations of Naik’s plays have already been published. ‘Sathecha Kay Karaycha’ is one of them.

It is a universal play which cuts across time, space, language and gender. Following the story of Abhay, an ad film maker and his wife Salma, an English lecturer. The play questions the constant conflict between recognition and contentment.

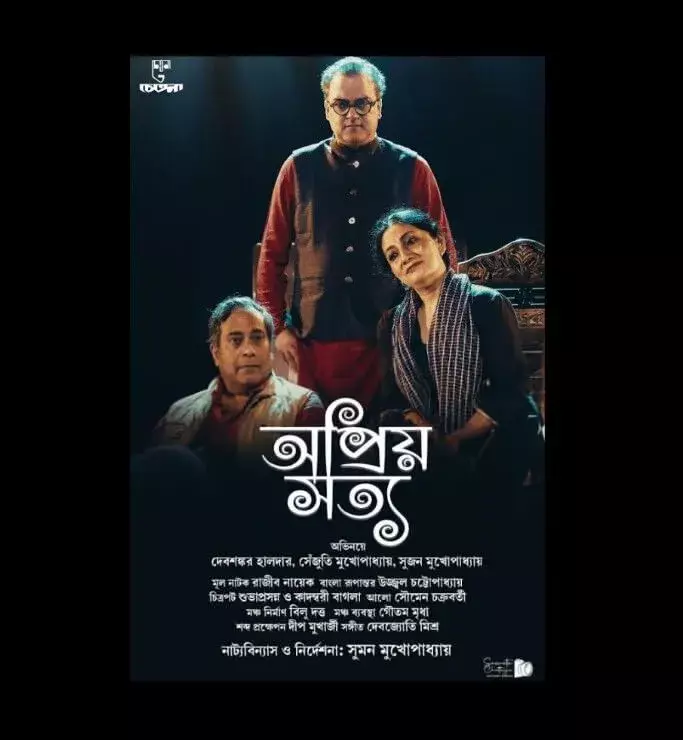

The play deals with the anxiety of its male protagonist Abhay (Debsankar Haldar) a successful ad filmmaker who is constantly dogged by feelings of diffidence, and uncertainty. He also nurses a ‘creative envy’ for Satya Nandi (Sujan Mukhopadhyay) who is acknowledged as an outstanding off-mainstream filmmaker, unbending on his principle of not commercialising his films. Though his utterances sound hollow despite their high-brow philosophy, Nandi continues to haunt Abhay’s life through the play.

Abhay’s wife Salma (Senjuti Mukherjee) is a lecturer of English in a local college, she becomes a shoulder to cry on, his sounding board, life partner and intellectual companion. But she has problems with her own college politics. She seems disturbed by them yet does not air her inner thoughts as much as Abhay does.

In Naik’s original performance, this intellectual filmmaker of art films does not appear on the stage at all. But Suman Mukhopadhyay, in this play, gives concrete shape to the character with a costume befitting his intellectual pretensions. He dons a long, white, kurta, a shawl thrown across his shoulders and a long pony tail hanging down his back.

The audience is left to interpret this parallel character and discover whether this man is for real, or whether he is the imaginary alter-ego of Abhay.

Abhay constantly feels threatened, never mind his success in his field, never mind his wife Salma who points out his drawbacks as well as offers him solace. She explains that since he has excelled in his chosen field, why must he be haunted by the ‘celebrityness’ of Satya Nandi.

Looked at from a different perspective, Satya may well be a concept for the ‘ideal’ which poses difficult questions of identity for Abhay. According to Naik, the playwright, even weeping may be indulged in organically or spontaneously, without a trigger. So, Abhay weeps in the play and we do not know why.

Salma, reading out to Abhay from Chaucer’s ‘Canterbury Tales’ for his “unique” ad film concept, also breaks into tears seated on her writing table without reason.

The narrative is often punctured with the sudden appearance of Satya Nandy, the “great director”. He steps in grandly, sits on a decorative armchair, and sometimes just strides across the proscenium mouthing bytes that are pretentious but sound intellectual.

Abhay says that stories need not follow the established and accepted sequence of a beginning, a middle and an end and can be narrated in any which way.

‘Unpalatable Truths’ also does not follow a linear storyline. In fact, it does not have what we commonly understand as “a story.” This makes the performance non-linear and character-driven.

The demands on the three performing actors are tremendous but veterans that they are, they offer a scintillatingly magical performance. They make ideal use of the proscenium space, furniture, property, white board at the back of the stage where Salma generally writes what she is talking about while Abhay wipes out things written. Is it an expression of expressing and then erasing?

The actors use their entire body for their roles, moving across the proscenium as if they belong to it, dancing, prancing, singing and everything that stands for “living.”

The music by Debjyoti Misra vacillates between loud ad jingles, Hindi film songs, and soft, Bengali numbers fitting into the lifestyles of the characters and the mood they are in at a given moment. Bilu Dutta’s art direction and the lighting by Soumen Chakraborty are both imaginative and innovative, enriching the performance without being loud.

However, the main flaw in the entire play is the heavy dosage of intellectual references drawn from famous writers, poets, filmmakers, and artists. It is not audience friendly and tends to intrude into the main narrative and the characters’ stories.

Debsankar Haldar as Abhay, Senjuti Mukherjee as Salma and Sujan Mukherjee as Satya (Sathe in the original) are performances you carry with you outside the theatre.

This adaptation of a Marathi play for a Bengali audience is a trend that widens the horizons of Indian theatre. It invites audiences to discover the richness of regional plays presented in their own mother tongue. Hats off to Chetana, director Suman Mukhopadhyay and his team.