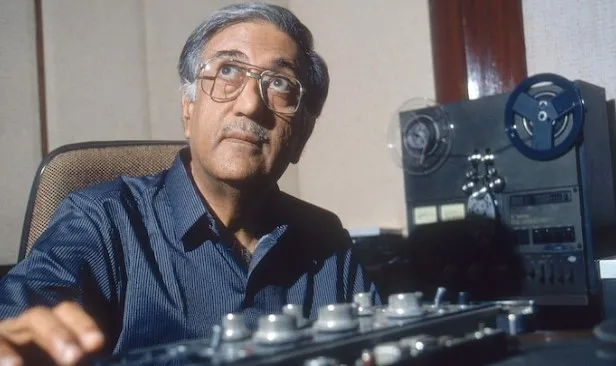

The Life And Times Of Ameen Sayani

When sound shaped our subliminal subconscious

Since there were no moving images in the 1960s, except in cinema halls, the open-to-sky courtyard of my small town home in Saharanpur in Western Uttar Pradesh, with a huge guava and jackfruit tree, and a sprawling, leafy tree which would scatter little, white, shiuli flowers like twinkling stars on the ground, was almost always resonant with a synthesis of lilting, melodious sound, or news and announcements in familiar voices. Sound, not image, shaped our subliminal subconscious. From early morning till midnight, when, inside the mosquito net and under the cosmic galaxy, we would sleep peacefully, like children protected from all the tragedies and evil of the world.

It was the sound of the radio. We had a huge Murphy radio with a tiny, luminescent glass window on the top-right, and we thought there was someone inside this big friendly box who was creating all the lovely voices, sound and music. I still have the radio with me, a precious family inheritance I have claimed from my childhood, which has taken me zigzag through a million corridors of known and unknown history, wars, tragedies, victories, life and death, tears and joy, excitement and suspense, and the magical songs and memories of yesteryears. Small was indeed beautiful.

Ameen Sayani (1932 to 2024), as an ever-lasting and evergreen memory, was undoubtedly one of them, with his velvet-sunshine voice of eternal friendship and uplifting romance. “‘Behno aur bhaiyon, jee haan, main hoon aapka dost, Ameen Sayani’!” At 8 pm sharp on Radio Ceylon. Every Wednesday.

Binaca Geet Mala. With the top ten songs of the week. Week after week, the entire nation remained glued to the radio, or, later, the transistor. That was the one hour every week which filled us with dreams and fantasies, reassured by the golden narrative of this great broadcaster and legend.

Sayani began his stint with Radio Ceylon in 1951. He was earlier a voice-over artist. This programme was broadcast for a record number of years: from 1952 to 1994, and continued in the early 2000s as well.

The programme began with a 30-minute slot, quickly became popular, and was a weekly rage in the 1950s, and after. It later became ‘Cibaca Geetmala’, since the Binaca toothpaste company wanted a change in its brand name. And, yet, in popular consciousness, it always remained as the etched memory of the original: ‘Binaca Geetmala’, with some of the finest songs of the era aired on Wednesday night. It later became integral as a hugely popular radio programme in Vividh Bharti and All India Radio (AIR) as well.

Ironically, the 1950s was also a time in Indian politics when B. V. Keskar reigned as the Information and Broadcasting Minister in Jawaharlal Nehru’s cabinet (1952 to 1962). In an absurd irony, and as an example of elitist puritanism, Keskar banished film music from AIR. Hence, AIR only ran classical music day in and day out.

Why Nehru, a symbol of modernity and non-dogmatic openness, allowed such prudish and conservative behaviour, remains an enigma. Indeed, in the following years, if an eminent person died, especially a politician, it would broadcast mournful classical music for three days. Keskar’s banishment of film music, in a certain inverted sense, also led to the huge popularity of Binaca Geetmala, since he had no control over Radio Ceylon.

This was also the era, with its lineage in the freedom movement, when the most brilliant songs were being written and composed in Hindi cinema. The Left-led Progressive Writers Association (with Munshi Premchand as its first president) and Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) had brought the highest realm of creative and aesthetic values inside ordinary homes, market places and roadside tea stalls, village squares and chaupals under a peepal tree, in railway trains and stations through the use of radio and transistors.

Their lyrics and music, eternally alive and pulsating till today, would be in every lips, with the songs of Mohammad Rafi, Shamshad Begum, Noorjahan, K. L. Sehgal and Pankaj Mallick, Geeta Dutt, Lata Mangeshkar, Asha Bhonsle, Talat Mehmood, Hemant Mukherjee, Manna Dey and Kishore Kumar, on radio. The greatest lyricist and musicians belonged to this era: Sahir Ludhianvi, Kaifi Azmi, Majrooh Sultanpuri, Madan Mohan, S. D. Burman, Naushad, O. P. Nayyar, Khayyaam, Shankar Jaikishen, among others. It was radio which made them integral to a nation’s deepest and most intimate essence in the post-independence era.

Radio Ceylon also had another great programme. Early morning old and vintage songs from 7.30 am to 8 am. The last song was always that of K. L. Saigal, and that is how, we would know, that now is the time to run fast, or cycle faster, because it is time for school! That is how, also, as kids, we learnt the beauty and purity of these singers, especially with Saigal saab, with his voice dripping with liquid intoxication and deep pathos, one of the most popular singers of his time. Mukesh sang his first song in life, in Saigal-style, a classic: ‘Dil jalta hain to jalne de…’

Born in 1932, Ameen Sayani’s roots were located in a culturally rich and refined family, trained in literature and the values of the freedom struggle. His mother, Kulsum Sayani, edited a fortnightly journal, ‘Rehber’, which, significantly, was inspired by Mahatma Gandhi.

It was also used as a tool of education and meant to spread enlightenment among the adult population of India. It was published in Urdu, Hindi and Gujarati. She was an active participant in the freedom movement, and worked for social reforms. She ran a school in Bombay to spread literacy among women. Her father was a personal physician of Gandhi. His brother, Hamid Sayani, was a big name in English broadcasting.

In a letter written from Panchgani (July 16, 1945), signed as Gandhi, the Mahatma wrote to her:

“Beti Kusum,

To whom should I write? And yet, how can I say ‘No’ to you? This is my message: I like the mission of Rehbar to unite Hindi and Urdu. May it succeed.”

Ameen Sayani’s life and times as a broadcaster is incredible. At one time, he would be doing 30 radio programmes in a week. He has given audio for, or produced, over 54,000 radio programmes and 19,000 spots/jingles since 1951. ‘Binaca Geetmala’ was conceived and crafted by him. This hugely popular programme in India and Pakistan also found its way across other radio channels in India and abroad: Red FM, Radio City, Big FM, Hum FM, UAE, Spice Radio, US, and the BBC. All India Radio, after the puritanical phase of Keskar, was forced to air it as one of its top programmes on Vividh Bharti in 1989.

Indeed, this was the era when the AIR Urdu Service was equally popular across India. Its programme ‘Akhbaro ki Rai’, broadcast at a fixed time, a matter-of-fact narration of current affairs and analysis in various newspapers, was keenly listened to across homes and roadside tea-stalls.

‘Taamil-e-Irshad’, a popular song show on audience-request, ran post-dinner, late in the night, and some of the finest songs of the era filled the night landscape of small towns and cities. From vintage songs in Dev Anand and Dilip Kumar’s films, Salil Chaudhury’s synthesis of western-classical and Indian folk music, songs from ‘Mother India, Mughal-e-Azam, Baiju Baawra, Pakeeza’, to R. D. Burman’s modern pop songs, this programme was the eternal sleeping pill which put the listeners to a sweet sleep in the night.

Besides, there were legendary news-readers like Devkinandan Pandey and Surojit Sengupta, household names those days. The radio commentary of hockey and cricket by legends like Jasdev Singh and Melville de Mello created a imagined playground where we could actually ‘see’ everything vividly – with the voice-narrative of the commentators, often reaching a crescendo or an anti-climax, when a certain goal would be missed, or a crucial catch would be dropped. Some of the greatest cricket innings and hockey matches were played on radio.

Amidst all this, stood out Ameen Sayani, with his endearing voice of friendship and refinement. His departure at the age of 91 reminds us yet again of the infinite loss of the great, magical romance of radio, which can never be replaced by any mass media, digital, audio-visual or otherwise, in this lifetime, or ever after.