How Votes Were Counted

How a national achievement has been overturned

I am proud of my country for two reasons. For the Indian brand of indigenous secularism, the rare spectacle of ordinary families living side by side for centuries, sharing their faiths, food habits and festivals. And for the homegrown election apparatus, not derived from colonial masters, that we have created to run a democracy, when we were catapulted into the modern world.

The tragedy of the last decade is the calculated destruction of both our national achievements by a cynical government and its captive institutions, leaving many like me lost and unhappy.

The founding fathers gave us an independent constitutional body, the Election Commission of India (ECI) to hold free and fair elections. The United States has no such agency. Unfortunately, the ruling party has now planted its agents in the institution and forced it to forget its mission.

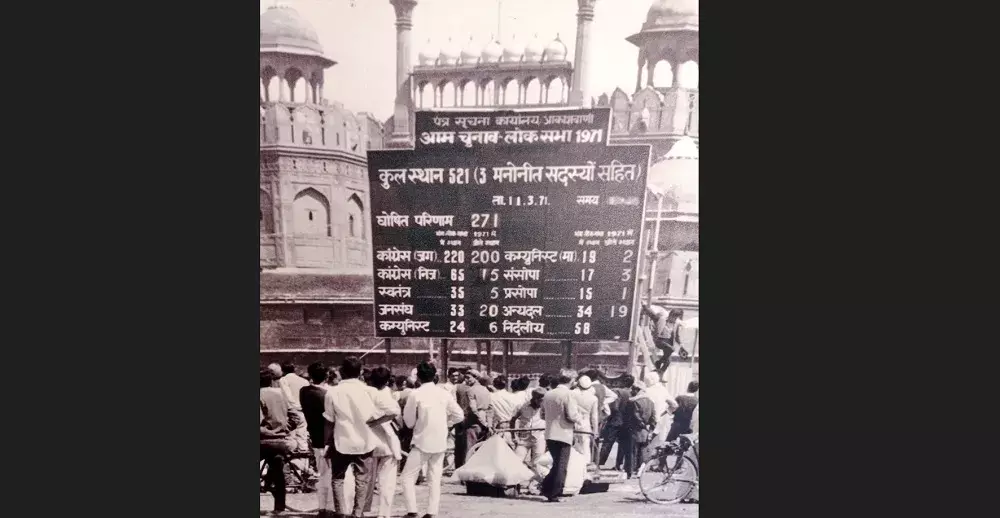

Every good practice developed to hold elections in the country since independence has been wiped out in recent years. To its eternal disgrace, the ECI has stopped the release of essential statistics, which it routinely released in the past-figures of votes cast and counted in Parliamentary and State Assembly constituencies.

The Supreme Court too, going against its own hoary traditions, has refused to safeguard democracy.

But, voters are up in arms, questioning the massive variations in ECI figures released at different dates, as in those put out recently in Maharashtra and Haryana. They have no faith in the reliability of electronic voting machines (EVMs)-they want results to be validated by a count of the paper slips (voter verifiable paper audit trail-VVPATs) generated while voting.

The State has even illegally imposed a curfew to prevent one village from holding a fresh election using paper ballots to reassure itself about the accuracy of the vote count. Have we all forgotten that democracy dies when citizens lose faith in elections?

The studied silence of the ECI on electoral data discrepancies mystifies persons like me, who have themselves held, supervised and stood for elections. Many civil servants who started working in the early 1970s could not function as Returning Officers (ROs) and conduct elections during their first postings as Sub-Collectors or Assistant Commissioners, because Prime Minister Indira Gandhi had suspended elections after declaring a national emergency in 1975.

Our first election experience came after the Emergency was lifted in 1977. I got my chance only in 1979, when the Janata Party lost power in the Centre and Parliamentary elections were announced.

As the first woman Deputy Commissioner (District Collector) of Karnataka, I was in the spotlight, since many of the officials around me did not think that a woman could do the job. I was marooned on the fringes of the State at a district headquarters without STD facilities, with a team of novices and a sprinkling of experienced officials. I remember being nervous, but, like many fellow citizens, who assist periodically in this great exercise, I was determined to be professional and objective. We all knew how much depended on us. We also knew that failure would wreck our careers.

Since then, I have several times supervised elections within and outside Karnataka and even participated in them as a candidate. Some things have changed over the years. EVMs have replaced paper ballots, teams of observers are mobilised to oversee elections and data is transmitted instantaneously on the net. But, the broad contours of election work have not altered.

By 1979, time-tested routines and procedures had been put in place to hold elections. Teams of officials drawn from different departments were organized, trained, mustered, equipped with polling material and personal supplies and despatched to polling booths in the eleven talukas of Uttara Kannada (Karwar) district, which were organized into the eight Assembly constituencies, that were part of the Parliamentary constituency for which I was the Returning Officer. Assistant Commissioners and Tahsildars were also appointed as Assistant Returning Officers (AROs) for each Assembly constituency to assist me.

On polling day, after voting ended, the Presiding Officer of each booth collated data about the number of ballots handed out to voters, spoilt ballots and tendered votes (disputed votes cast by those who find that votes have already been cast in their name by other persons). These had to add up to the number of ballots that (s)he had collected from the office of the Returning Officer while taking charge of her polling booth and her team. They had also to tally with the total number of voters, whose names had been identified on the marked voters’ list used at the booth.

These signed documents and ballot boxes, sealed in the presence of the agents of candidates, were taken to the ARO’s office. The Presiding Officer was not allowed to go home without reconciling her data and handing over the boxes and documents. AROs immediately passed on figures of the votes cast in their Assembly segment to the RO, placed the sealed boxes in the strong room and put police personnel in charge of security before going home.

The R O verified figures and totals for each Assembly segment, added figures of postal ballots received in her office (these were securely kept by the R O’s second-in-command) and transmitted the information to the Chief Electoral Officer at the State capital before going home. Since my headquarters phone had no STD, data was collected and sent on the police wireless. The CEO and her staff too did not leave office without obtaining data from all constituencies, reporting it to the ECI and releasing it to the press and public.

Even with the primitive facilities available in the late 1970s, actual figures of votes cast were always available a few hours after voting. Why is the ECI finding it impossible to give them now?

Clearly the Commission, which claims that replacement of paper ballots by EVMs has vastly improved efficiency, is confessing that the quality of data has deteriorated. Presiding Officers still use marked voters’ lists, when EVMs are handed out to voters and confirm that they are operated. Has the ECI dropped the requirement for Presiding Officers to tally and reconcile polling booth data and report it up the line to the ARO, RO and CEO?

There is something very rotten in Nirvachan Sadan, when it refuses to publish the number of votes cast in a constituency and replaces the figure with voting percentages that are repeatedly changed, several times after an election.

In the 1970s, CEOs were focused on completing the counting of votes as quickly as possible after Election Day to ensure that ballot boxes were not tampered with in strong rooms. Now that the election process is often staggered over several rounds and weeks, this is no longer a priority.

We began the counting process for the 1979 election early in the day, checking seals on boxes, taking them out of strong rooms and emptying them at counting tables, where votes were counted by hand in the presence of the counting agents appointed by candidates, under the supervision of AROs and the RO. As each round of counting was completed, interim results were sent to the CEO for public release.

When all boxes had been counted, the ARO in charge of a room prepared a final tally of the votes gained by each candidate and invalid or spoiled votes. The total had to agree both with the total number of votes cast on election day and the totals recorded for each ballot box and polling booth. Postal ballots were counted by the RO. These numbers were then added up and reported to the CEO. No official drafted for election duty, including the RO was permitted to leave the building till these tasks were done.

I remember this vividly, because the report to be sent from my office was delayed for some time in 1979, when the ARO of the headquarters Assembly constituency could not reconcile his figures and was forced to do a recount. We used no handheld calculators or PCs then, but we declared the winner before midnight on counting day.

The more we saw countries around the world struggling with the conduct of elections, the greater our pride in our own well-honed procedures. A joke circulating in Karnataka offices during the contested Bush versus Gore Presidential election was that an Indian Election Sheristedar (Superintendent) could be exported to the US to clean up its counting techniques. We cannot make any such boast today.

The chaos reigning in the ECI indicates that it has lost or deliberately abandoned best practices learned after decades of experimentation and experience. Voters, political parties and candidates have a right to know why. But, the ECI is not budging. It will not disclose whether it has diluted age old standards when it has a vastly improved and automatised system. It is stifling doubt and dissent, when it could mend its ways and respond to complaints.

Much of the current cynicism would be allayed if it returned to the old practice of announcing the numbers of votes cast on election day and allowed EVM data to be validated by counting VVPATs when figures do not tally. This would also give it a reality check on the extent of error to be expected during a normal election.

By hiding its head in the sand, it is inviting suspicion and speculation and holding the country up to contempt around the world.

Renuka Viswanathan retired from the Indian Administrative Service. The views expressed here are the writer’s own.