NEET Injustice, And The Net Of Deceit

The massive government machinery has failed

Thrasymachus in Plato’s ‘Republic’ says to Socrates, “I proclaim that justice is nothing else than the interest of the stronger”. Socrates, after an elaborate dialogue with Thrasymachus and his supporters, asked whether medicine considers the interest of itself or the body.

And then expands by stating that no physician “in so far as he is a physician, considers his own good in what he prescribes, but the good of the patient”. Plato writes that, through persuasion and logic, Socrates could ultimately convince Thrasymachus that “injustice can never be more profitable than justice”.

The question that has become extremely critical in our public discourse is whether Thrasymachus or Socrates is right, in their respective claims over justice.

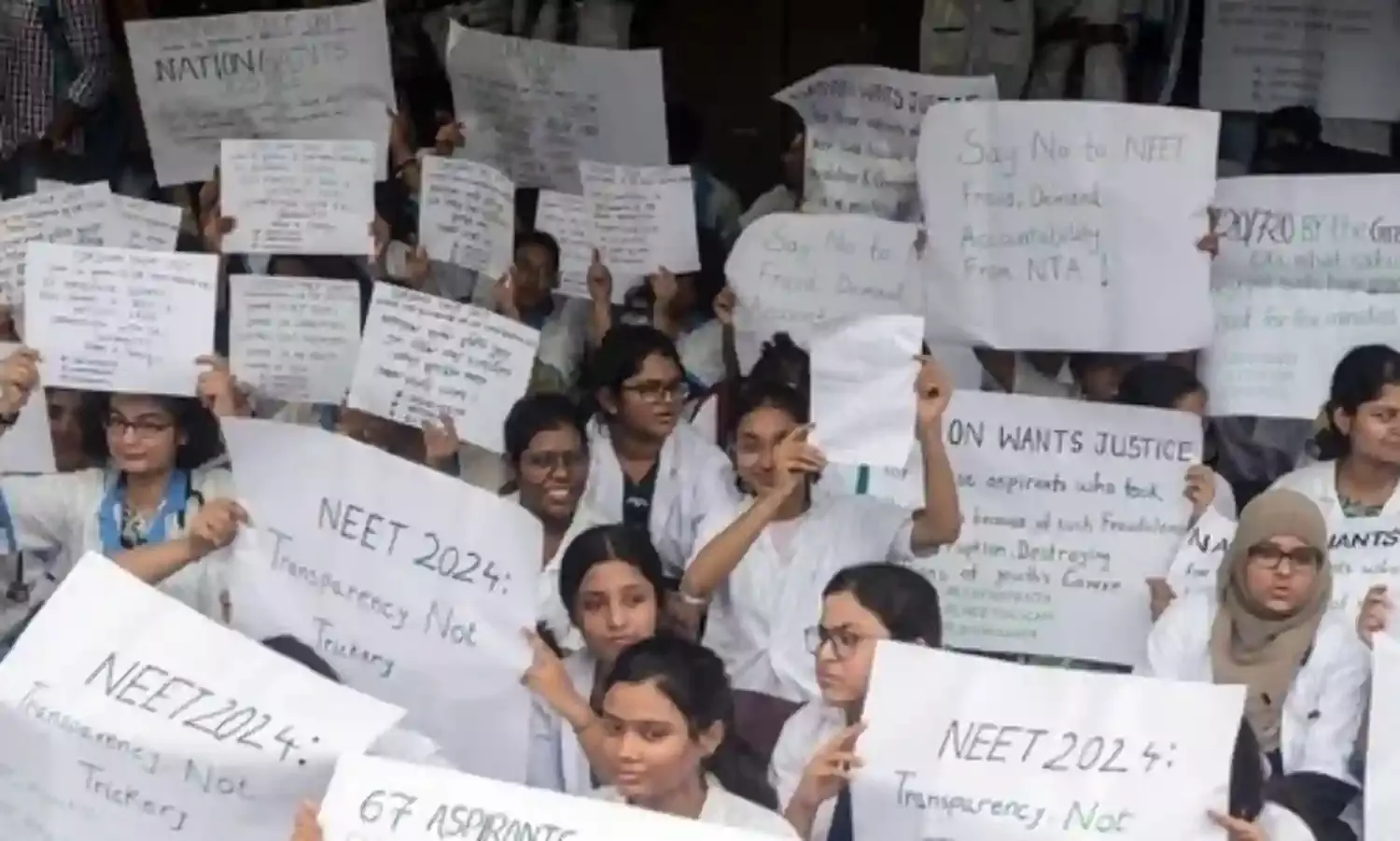

A massive government machinery has failed to deliver a clean and efficient public examination successively. Corrupt practices have flourished and the interests of the stronger have prevailed.

Innumerable students have spent money, time and energy preparing for the gruelling NEET and NET tests only to find that their efforts have gone to waste. In a democracy, the idea of merit holds great prestige.

One is supposed to be rewarded for meritorious conduct not only by being provided with a job or some material prize but also by laying down a level playing field. A student who cannot get a pass in that exam can always be told that the opportunity for success or failure is equally true for all students appearing in that exam.

Much like the doctrine of isonomia (equality before the law), the idea of being equal in the arena of merit is the cornerstone of a democratic examination system.

The legitimacy of a democratic state lies in its ability to convince its citizens that the public space has not been cornered by the influential and the rich by their ability to clinch private deals and therefore get access to the limited resources that society has to offer.

The discourse of merit and meritocracy claims that learning and skills are widely distributed across the population. No one has an exclusive claim to a certain position because one is born supposedly with extraordinary talent.

Democracy allegedly demolishes the idea of powers derived from birth (status) and replaces them with abilities learnt in due course of time by formal and informal processes (socialisation). One of the ways that the democratic polity ensures that this idea of merit finds pride of place is by making prized and scarce social goods available through a system of legal rationality.

When the edifice of the legal-rational is eroded the foundational basis of the democratic state is dented as instead of discrimination by achievement (or lack of it) it becomes discrimination by other means.

One of the most significant ‘other means’ is the use of money power, a global theme made prominent and critical with the advent of neoliberalism. Neoliberalism’s mantra is that money can buy anything, and the market is the best allocator of values and resources.

This economic dogma has a sociological impact – it creates persons who are only interested in themselves, their mobility, their advancement at any cost and the incessant drive to consume more and more. The scams that we are witnessing now are a mere reflection of this sociopathy that has inebriated the middle and upper-middle classes for whom the race must be won at any cost.

The abdication of the State from welfare has many supporters who feel that welfare and positive discrimination are all about giving fish for free to those left out instead of teaching them how to fish. The Right Wing riding on this smart but vacuous rhetoric misses the point completely and constructs a hubris that debilitates freedom for the vast majority.

Or to put it differently, why is it that the majority of the people are left without the wherewithal to buy their fish? The answer of course is obvious save for those who are blinded by their ideological prism.

Yet, one must acknowledge that those who are blinded are blinded by privilege which does not allow them to accept that their class may not have merit. It is this social myopia that produces the tutorial factories that are tasked to produce ‘merit’.

India is unique in that it has now been able to construct entire townships whose economy depends on the multitude of teaching shops, churning out merit for their eventual journey to the institutions of higher education where they would be further embellished with yet more hubris for themselves.

The NEET and NET scams are testimony of the ability of neoliberalism and late capitalism to capture spaces (or attempts to capture spaces) with money power. These scams are not episodic instances of evil but a systemic challenge to the very idea of education, good citizenry, a democratic polity and in the end, of prime concern, justice.

Ironically, the foundations of liberalism are not being shaken by the onslaught of the left-radical revolutionaries but by the very people who ideologically swore by the principles of liberty and freedom.

What a scam such as what we have witnessed does, one may argue, is that it provides the student with a feeling that one can buy one’s way through education and that which brings satisfaction and pleasure as an end is ethical. This deontological argument that the end justifies the means plays the intellectual sidekick to the rapacious and dangerous mainstream thinking of the right.

It is also not an accident that these scams are breaking when a right-wing populist party is in government. Despite the rhetoric of sanatan dharma and the supposed following of ancient and venerated ethics as its lodestar, the BJP and their patrons have through their economic and social policies encouraged the young and their parents to eschew the very ethics and public morality that the ancient religious texts would have enjoined them to follow.

Those left out by this system know that given a chance they too could have cracked a difficult gatekeeping exam or done better in life except that the state and its managers have compromised with honesty and killed the very essence of healthy competition.

The marginalised are aware that those who are at the top are in most cases catapulted to it by the wealth and status of their parents. This then must produce alienation and extreme apathy toward the system, which is not a good sign for a country that aspires to be a robust economy, a teacher to the entire world and an important political player.

If the manufactured rot in the higher education sector cannot be stopped, we may have to agree with Thrasymachus that “… justice is nothing else than the interest of the stronger”. If that is what the BJP and the Indian prime minister desires, then they have no moral right in the comity of nations.

One can only hope that with a large Opposition in the Parliament, the voices of those who think that justice matters would be championed, and young students assured that their future is not in the hands of those who are insensitive, unjust and deceitful.

SURAJIT C MUKHOPADHYAY is Dean of Social Sciences, Sister Nivedita University, Kolkata. views expressed are the writer’s own.