The Mao-Lisa Smile

Memories from the Dada-Abu era

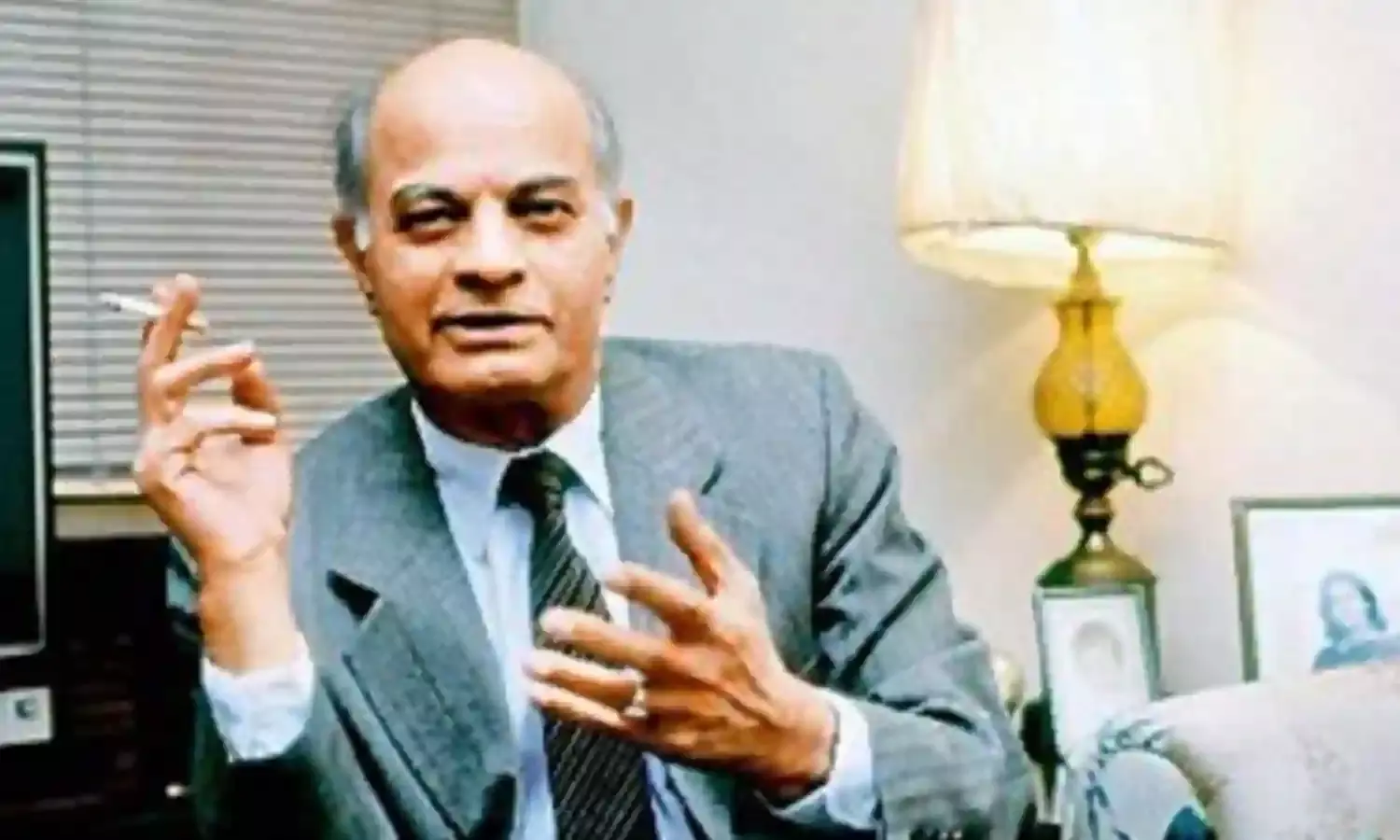

The passing away of Subhash Chakravarty last month has not been much noticed because Subhash or Dada, as some of us called him, as a long time chief of Bureau of ‘The Times of India’ did not have the exposure of, say, a Kuldip Nayar. More than his readers, fellow journalists would remember him. He was more of a newshound than a popular writer.

Editors got hooked on him because of the vast quantities of information he furnished for the editor to process. When N. J. Nanporia, the most erudite of editors, moved from The Times of India to ‘The Statesman’, his unofficial but regular “tipster” was Dada rather than his counterpart who was on the paper's staff.

The man who could walk unannounced into the offices of the most powerful in the land, was also extremely lonely in his private life. His extraordinary access to politicians like Pranab Mukherjee could be explained in parochial terms too, he could not conceal his Bengali chauvinism.

In this he was not dissimilar to the late Abu Abraham. A superb cartoonist, Abu was also a Malayali chauvinist, a tendency which erupted every time he touched on “north Indian culture”.

Dada and Abu have crept into memory simultaneously because they link up in different ways with a China story gestating in my mind.

Among the many remarkable cartoons the late Abu Abraham sketched, the one he prided most was of Mao Zedong walking up to an Indian diplomat, Brajesh Mishra, smiling mysteriously, eye contact and all. The enigmatic smile, at a time when relations between two nations were in a “chill” phase, became the subject of continuous discussion and punditry. Abu’s caption of the cartoon were words of inspiration: “Mao-Lisa”.

The Mao-Lisa smile may well have been one of the ingredients in K. R. Narayanan was named ambassador to Beijing in 1976 after a 14 year lapse. The date of Narayanan’s appointment overlapped with the Emergency.

When Indira Gandhi was routed in 1977 and Morarji Desai became Prime Minister, the Ministry of External Affairs fell to the lot of Atal Behari Vajpayee. The office he occupied near South Block’s main staircase was exactly the one that Pandit Nehru occupied as Prime Minister.

“I am about to occupy the chair on which Pandit Nehru sat.” Vajpayee was full of emotion.

Among his earlier visits as Minister for External Affairs, Vajpayee and his cerebral Foreign Secretary, Jagat Mehta, embarked on, was to China, in February, 1979.

N. Ram, Dada and I were part of a small team of journalists invited to accompany the delegation. Dada was never short on tips on chopsticks at the Great Hall of the Peoples, the essential protocol of climbing the Great Wall, with an empty bladder. In February’s biting cold there would otherwise be that embarrassing search for a toilet.

One big advantage of having Dada by our side was actually quite priceless. Since he called up his editor, Girilal Jain twice a day we were regularly updated on how our stories were faring.

The Editor’s approval of the drift of one’s stories was clear from the display given to what one was writing. It was all very satisfactory until one reached Hangzhou, the great cultural centre.

After a memorable banquet by the local party chief, we retired to our rooms in an exquisite hotel. This was usually the time for Dada to walk to the press room for his confabulation with his editor.

Such was Dada’s demeanour that it appeared to those who were listening to the conversation that Dada was actually scolding his editor. That was his style.

This particular conversation with Girilal Jain ended dramatically. Dada let the handset dangle by the spiral cord, rather like the climax of Dial M for Murder. He ran toward Jagat Mehta’s room and began banging on the door. “Jagat, open the door” he thundered ominously, “China has invaded Vietnam”.

It was feared from the first day of Vajpayee’s visit that Deng Xiaoping might actually do what he verbally threatened: “teach Vietnam a lesson.” Some action was expected after Vietnam occupied Kampuchea and removed the Khmer Rouge supported by China.

Considering that the Indian Foreign Minister was in Beijing on something of an epoch making visit, military action against Vietnam without as much as taking the visitor into confidence was construed an insult. What compounded the insult was the fact that the Foreign Minister of Yugoslavia who was in Beijing at the same time, was kept in the loop.

What took place in Vajpayee suite that night was something of a somber variant of a pajama party. Vajpayee’s mind was made up. He cut short the visit and returned home via Hong Kong.

This was Chinese behaviour at a time when Deng’s four modernisations had barely been announced as state policy. China, like India then, was a poor, developing country.

Did China deliberately insult Vajpayee? I would say no. The element of secrecy with India was dictated by India’s deep relations with the Soviet Union. Vietnam at this stage was largely in the Soviet camp.

What Vajpayee’s successor, Narendra Modi is coping with is China rising to the height of Gulliver, challenging not India, but the US, India’s patron. Circumstances of a changing global order have placed India on a sweet spot, wooed by both sides. In this situation, India’s commitment to strategic autonomy is credible.

This credibility has to be sustained by managing the autonomy of action without ever looking like the leaning tower of Pisa.

Village ‘Nats’ walk on ropes tightly held by two poles. A fall, if ever, is after all only before a small village audience. A high wire act before a global audience, the one India embarked on demands exceptional agility.

Just because we are satisfied with the optics of the US visit, we cannot let our guard down. Our slipping into a virtual mode for SCO will have the world scrutinise the shift. Strategic autonomy as a policy will have to be sustainable. As a trick it will be found out.