West Bengal Still Relies On Its Public Health System

R. G. Kar Medical College rape has exposed a deep rot

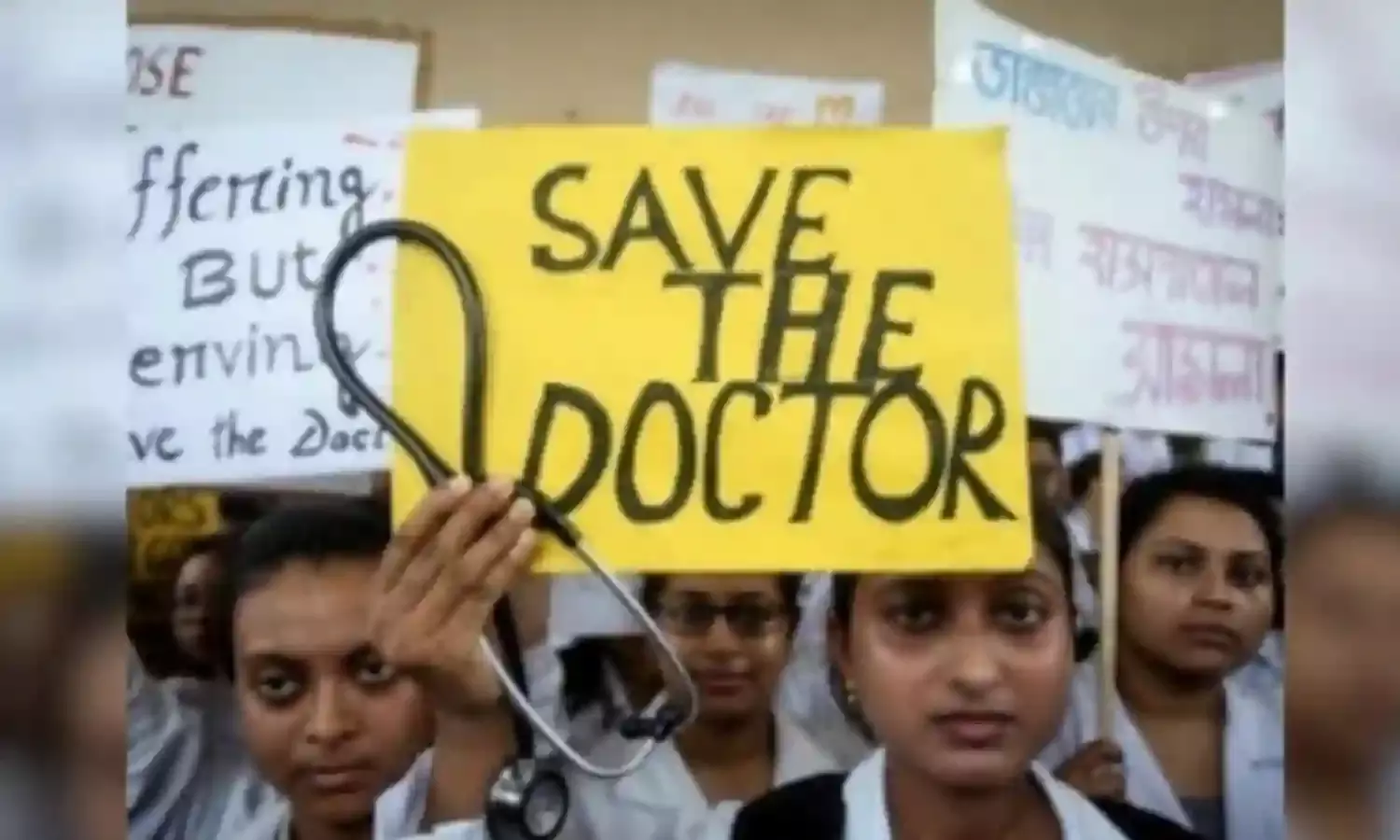

The past month has been extremely distressing for the people of West Bengal. They woke up to the news of the gruesome murder and rape of a young female post-graduate medical student on duty on the morning of August 9. Since then, disturbing details of alleged institutionalised corruption at R. G. Kar Medical College surfaced, exposing the governance issues in medical education as well as the public health sector.

Ironically, public health service, which should concern all, is the least talked about subject and, consequently, receives low priority in public policy. That way, the recent spotlight on infrastructural issues, shortage of physicians, and especially the working conditions of resident doctors is encouraging.

However, the resident doctors have been on strike for more than a month, and the unintended consequence of this is that this has disrupted the public health service provisioning significantly.

According to the state, hundreds of thousands of patients have been denied treatment, particularly in medical colleges and district hospitals. Besides, there have been several reported deaths due to non-receipt of care.

However, these numbers have been vehemently contested by the striking docs, and the stalemate is continued. Perhaps a look at the current stock of West Bengal’s human resources for health, in particular the physicians, would be helpful to get some clarity on the actual situation.

According to the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW)’s data, West Bengal had 77664 registered doctors (Allopathic) as of 31st December 2020. However, assuming that 27% (based on an estimate from a study) of them had either died, retired, stopped practising, or emigrated, only 56695 allopathic physicians could be considered to be currently available for service.

Like in other states, the majority of allopathic physicians either have independent practice or are attached to private hospitals. As per the MOHFW, only 8074 allopathic doctors (excluding dentists) were with the government in 2020.

Hence, the strike of junior doctors numbering 7200 (as quoted by different sources) would understandably affect the public health service system, particularly the provisioning of tertiary care through medical colleges and district hospitals.

Also, deaths represent extreme health outcomes, and therefore, relying only on mortality indicators would not reveal the actual health consequences of treatment denials and delays.

Let me now say a few words about the health service system and overall health situation in West Bengal. Though the health care system has become highly commercialised like the rest of India, public health facilities are still heavily utilised by the people in Bengal.

When you visit a public hospital, you will notice a constant flow of people entering and exiting the facility, with queues of patients before clinical departments. This is the usual scene. In fact, West Bengal leads in the utilisation of inpatient services from government facilities across India.

According to the latest health survey (2017-18) conducted by the National Statistical Office, public hospitals account for nearly 70% of hospitalizations (excluding childbirth) in West Bengal, a much higher proportion than in Kerala (38%), Tamil Nadu (50%), Gujarat (31%), Maharashtra (22%), Uttar Pradesh (27%), Bihar (38%), and many other states.

Additionally, public health facilities treated almost 30% of the ailments that did not require hospitalization. When these data are broken down by social and economic status, it is revealed that while people from across castes and classes rely on government health facilities, those from rural (74%), poorer (79%), and tribal families (89%) depend almost entirely on public hospitals for inpatient care.

While West Bengal hasn't performed well economically in recent decades, it has made significant strides in the social sector, particularly in health. One way to evaluate the state's performance is through its health outcomes, such as mortality indicators.

These indicators not only reflect economic and social inequalities but also provide valuable insights into the effectiveness of health interventions. In West Bengal, the infant mortality rate (IMR) decreased from 48 per thousand live births in the 2000s to 19 in 2020.

This places West Bengal behind only Kerala (6), Tamil Nadu (13), Maharashtra (16), and Punjab (18) in terms of both IMR and life expectancy at birth. Notably, the decline in IMR during the same period has been faster than in wealthier states like Gujarat, where it dropped to 23 from 50 per thousand live births.

It is important to note that West Bengal is not only poorer than many states but also more populous. Yet, fewer parents in Bengal experience the loss of a child, and, on average, Bengalis live longer than most Indians.

This substantial reduction in child mortality, in part, was achieved through near-universal immunization of children aged 12-23 months against common childhood illnesses and institutional deliveries. The reduction in mortality, as well as increased school attendance among girls, has led to a remarkable decline in fertility.

The total fertility rate (TFR), which indicates the average number of children per woman, shows that West Bengal has experienced a larger decline in TFR compared to many other states in the last 15 years. In fact, according to the National Family Health Survey (2019-21), West Bengal has the lowest TFR in the country at 1.6.

The evidence from the household consumption expenditure survey (2022-23) corroborates that West Bengal performed well in achieving the health-related SDG goal, namely SDG 3.2 which focuses on universal health coverage. Unlike other states, West Bengal did not adopt the national Ayushman Bharat Yojana but instead introduced its own social health insurance program called Swasthya Sathi.

The survey revealed that almost three-fourths of households had at least one member covered under the state-sponsored health scheme in 2022-23, which placed West Bengal ahead of other states in achieving universal population coverage for hospital care.

In contrast, only one in five households are covered by Ayushman Bharat Yojana. More importantly, Swasthya Sathi performed better in ensuring access to hospital care for the beneficiaries compared to Ayushman Bharat Yojana.

Clearly, the state has made substantial progress towards the ultimate goal of good health at low cost in recent decades, and it will do better if sincere efforts are made to address the systemic issues brought to light by the current crisis.

Addressing these concerns would also greatly help in restoring the people's confidence in the state’s health service system.

Dr. Soumitra Ghosh, is Associate Professor and Chairperson Centre for Health Policy, Planning and Management, School of Health Systems Studies, Tata Institute of Social Sciences. Views expressed are the writer’s own.