The Disappearance of Saroj Dutta

A scathing documentary, now released on an OTT platform;

Sadly, people link the disappearance of the irrepressible, gutsy journalist-cum-revolutionary Saroj Dutta, with Uttam Kumar’s running away to Bombay, to hide from any repercussions by those who knew he was witness to Dutta’s merciless killing. Dutta’s body was never found. The first and perhaps only documentary on Saroj Dutta titled Saroj Dutta and His Times (2018) has just been released online. It can be watched worldwide on a pay-per-view basis on Movie Saints.com.

The film was jointly directed by Kasturi Basu and Mitali Biswas. Kasturi Basu is a filmmaker, social activist, science researcher, occasional writer and editor based in Kolkata. She is a physicist, an alumnus of Jadavpur University, University of Cambridge, and Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey. Basu is a founder-member and film movement activist with the Kolkata People’s Film Collective and co-editor of Pratirodher Cinema, a magazine on cinema and counterculture.

Saroj Dutta and His Times is her first documentary. Mitali Biswas is a social activist and has worked as a freelance journalist (1998-99). She was on the editorial board of Protibidhan, a magazine dedicated to women’s movements. The third person helming the project is Dwaipayan Banerjee who wrote the script, did the research and was an associate editor of the film. He is an independent documentary filmmaker, activist, editor and researcher, based in Kolkata. He is an alumnus of Presidency College and Calcutta University.

The team decided to make a feature-length documentary not only on this great man but also, the political-historical context through which Saroj Dutta journeyed. It reaches beyond being a biographical documentary through defining the history to which the man belonged.

Saroj Dutta was a poet, a journalist, an excellent translator, a revolutionary and an iconoclast. Few of those born after 1971 have even heard his name, much less, the kind of political journalism he gave birth to. He was always standing beside those who were being tortured, marginalised, abused and oppressed for reasons that were never explained because the reasons did not exist.

In 1971, Saroj Dutta disappeared from the city of Calcutta. His was a copybook case of forced disappearance amidst widespread State repression on communist rebels during the Congress Rule in the State. A secret killing that has since become part of the urban folklore, a crime the State denies till date. His virulent pen rejected warnings and threats that came because of his fearless columns. Threats that led to his disappearance.

Kasturi, who was not born when this happened, says, “what intrigued us the most was the complete absence of (non-fiction) moving images that recorded this very important period in our history. No documentation, no raw footage, except a bit in Louis Malle’s Calcutta 1969 exists in the public domain covering this period in history. This is strange because cameras were prolifically used to cover incidents and events. Fiction films had many references to the Naxalbari uprising but they were almost completely centered on a romanticized version of urban, educated youngsters from elite colleges of Kolkata or New Delhi.

As if the Naxalbari Movement was all about an urban adventure! None of them even tried to get into the rural roots of Naxalbari, the long-standing, agrarian question and the peasants’ heroic rebellion that evolved into a powerful, political movement questioning an exploitative State and society in really radical ways. Not one film depicts how the Naxalbari Movement made radical critiques of middle-class icons and talked about bringing subaltern issues and peasant icons to the forefront. Our film is aimed at filling in these yawning blanks in a segment of the history of West Bengal.”

Why choose Saroj Dutta over other Naxalite ideologues and icons? “His life story reads like pages pulled out of a thriller, only, this was real life. His killing was spectacular in its brutality. It was part of urban folklore, with a star like Uttam Kumar having witnessed it. Other than Charu Majumdar, Dutta was the only top tier leader of the Naxalbari movement who was abducted and killed, and declared ‘missing’. His killing was not due to fiery public speeches or instigation.

His only weapon was his razor-sharp, fearless pen that never stopped putting on paper what he felt was wrong with the party he once proudly belonged to – the CPI which later became the CPI (M). Here was a man who took bullets for wielding his only weapon – the pen! In that sense he is in the league of revolutionary poets/journalists like Victor Jara, Federico Garcia Lorca or Julius Fučík who were well-known public intellectuals assassinated for their communist political beliefs. So, his story is an intriguing one to tell,” say the three.

The film tries to tell a complex story of those times. It goes beyond one man’s story and becomes the story of a historical period of which S.D. was a passionate chronicler. The film uses some of his immortal poetry and some of his translations of poets Chen Yi (My Address to Death in its Face), Patrice Lumumba (Dawn in the Heart of Africa) and Nikola Vatsarov (To the Hungry Children).

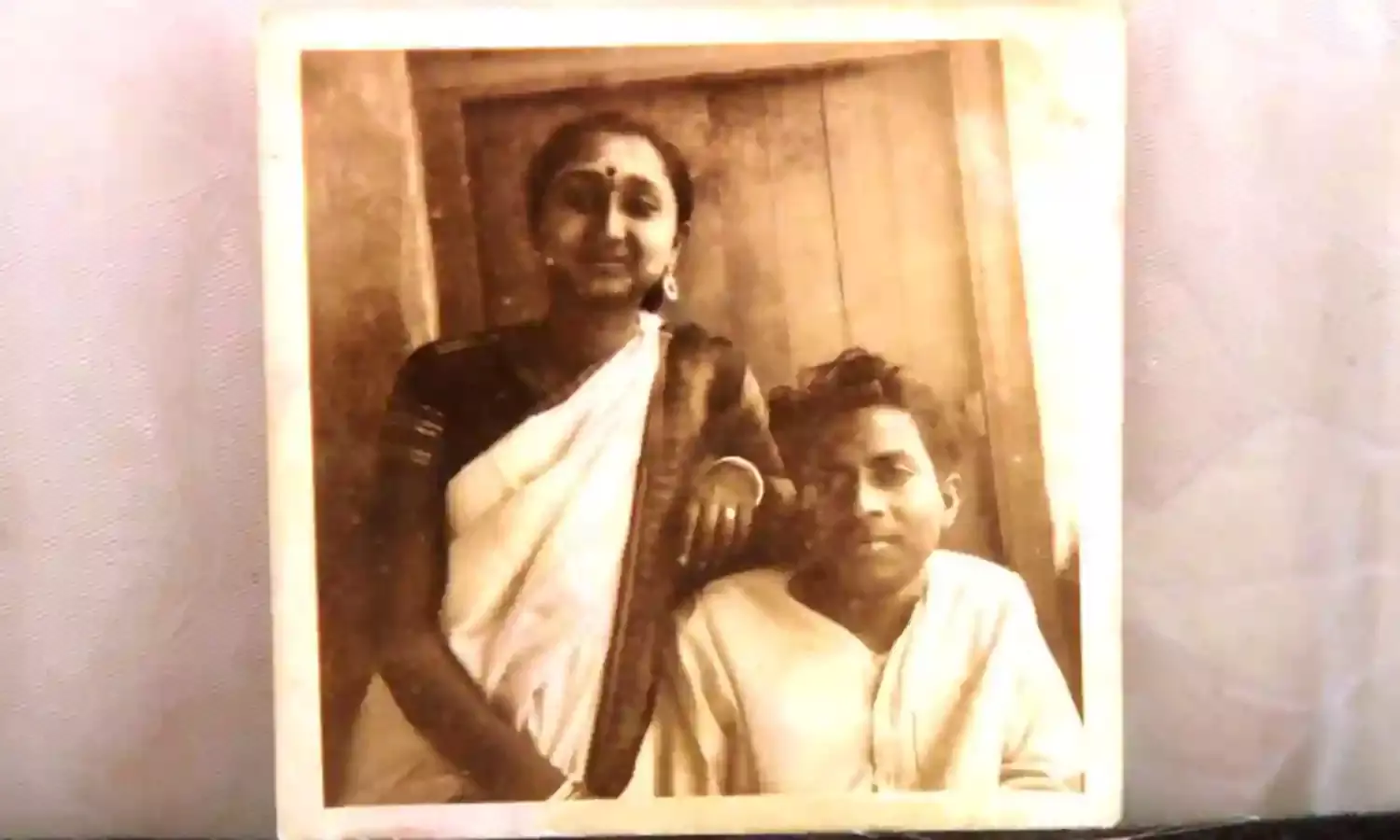

Imaginative aesthetics used by the filmmakers include the superimposition of the yellowed pages of newspapers in which Saroj Dutta wrote, over the visual images of the person writing. The directors’ interaction with people close to Saroj Dutta, including his wife, then in her 80s, is occasionally dotted with a voice-over narrating the story of a unique life that vanished from the face of the earth.

Saroj Dutta began as a journalist with Amrita Bazar Patrika. This was followed by Parichay, a journal published by undivided CPI, Swadhinata, the mouthpiece of the undivided CPI before it split in 1964, Desh-Hitoishi, the mouthpiece of the CPI (M) till the Naxalbari uprising in 1967 and Deshabrati, mouthpiece of the CPI (ML). He also contributed to Liberation, the English mouthpiece of the CPI (ML) and other Bengali journals like Arani and Agrani.

The songs are chosen as markers of immortalized numbers that sparked the Naxalbari movement. Alongside songs composed by cultural activists such as Ajit Pandey, Dilip Bagchi, Pratul Mukhopadhyay, Subbarao Panigrahi, one can also hear the long lost songs written and composed by peasant activists. Activists such comrade Shirril Oraon, who was semi-paralysed while the film was being shot but sang Bangla, Hindi, Nepali, Sadri and Jharkhandi songs.

The songs of Rongili Biswas that were used in Utpal Dutt’s play Teer on the Naxalbari uprising have been used written by Sukra Oraon and Kalu Singh. “We chose these brilliantly political and indigenous songs alongside a couple of known songs to enrich the politics of iconoclasm and reclaim people’s icons which is a motif that keeps recurring throughout the film,” said Basu.

The directors created a strategic sound design that crosses national borders and assumes international significance. These are: sounds from Peking Radio which Indians would eagerly listen to during the heyday of the Naxalbari movement. The directors have juxtaposed the soundscape on to the archival footage of newspapers and newsreels. Every single frame, sequence, interview, images of Bengali newspapers for which Saroj Dutta used his razor-sharp pen to instill in the young the fire to rise against injustice and brutal violation of human rights, gives the film its rich form in harmony with the content. Old photographs of the family and Dutta at different stages of his life dot the space.

The directors and the screenwriter have inter-woven the three narratives effectively, both as a dramatic strategy as well as an aesthetic exercise to make the 115-minute footage interesting and exciting. The three narratives are: Saroj Dutta’s personal journey with his evolution leading to his killing; the peasant uprising in Naxalbari, and the urban uprising of students and youth in Kolkata.

These narratives are threaded through a contextualization of lines from Dutta’s poetry, and editorial writings superimposed over the interviews, songs that organically evolved from the peasants of Tebhaga, Telangana and Naxalbari movements, and archival footage of newspaper clippings and newsreels of world events drawn from China, Vietnam, France and the Congo which left a deep impression and resonances in the Naxalbari movement rising in India.

This is truly a film for the archives, a documented record of the political history of West Bengal during the 1970s against the story of a true crusader, whose dead body was never found.