'Vital that Governments Understand the Experiences of Rape Survivors': Report

Faulty laws and implementation increase women's vulnerability to sexual violence;

Despite the high prevalence of sexual violence in south Asia, the response of the criminal justice system in various countries has been found to be severely lacking. A new report reveals that laws on rape in six Asian countries, including India, are insufficient and often pose greater barriers to survivors’ access to justice.

The report—released by Equality Now, an international human rights organisation and Dignity Alliance International—analyses laws in India, Bangladesh, Nepal, the Maldives, Sri Lanka and Bhutan to identify problems faced by women and girls attempting to access the criminal justice system.

Taking a “survivor-centric approach”, the researchers held discussions with survivors, activists, lawyers and other stakeholders and found that protection gaps in laws and implementation failures of existing policies increase women’s vulnerability to sexual violence. They point to long delays in investigations, intrusive unscientific medical examinations, low conviction rates, and added pressure on survivors to “compromise” as some of the major hurdles.

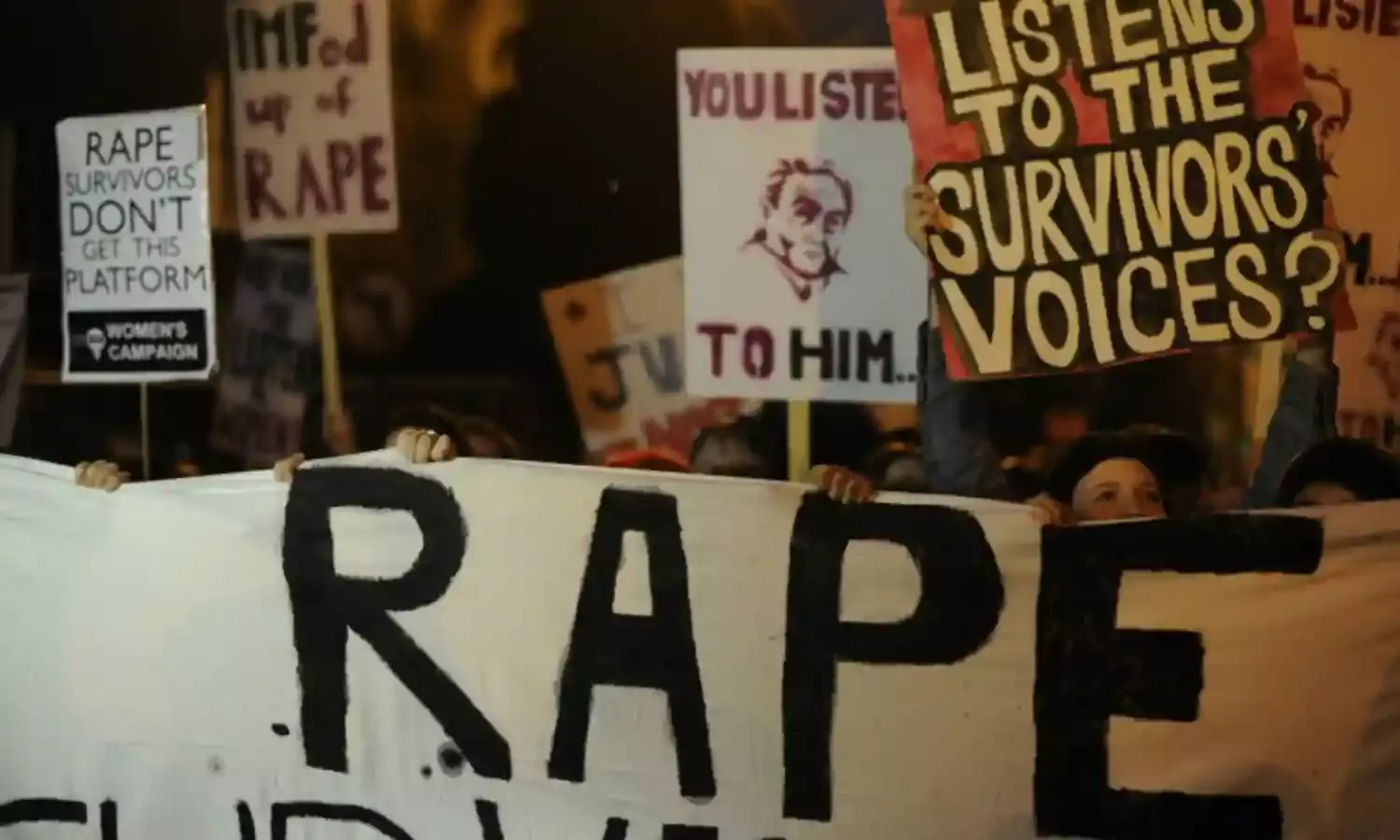

“Despite the widespread public protests against sexual violence which have occurred across South Asia in recent years, including the high-profile outcry over the Hathras gangrape case in India, governments across the region have still largely failed to implement meaningful, systemic reforms to address challenges within criminal justice systems faced by survivors,” said Divya Srinivasan, a human rights lawyer and South Asia Consultant at Equality Now, and a lead author of the recently released report.

“In addition to analysing gaps in rape laws, during our report research we heard directly from rape survivors about the various obstacles faced and the dire reality is that for the vast majority there is little hope of accessing justice,” Srinivasan told The Citizen.

Admittedly, the report only deals with cases pertaining to women and girls. It acknowledges that men experience sexual violence and that such cases go largely unreported, especially as existing legal provisions do not provide sufficient remedy to transgender or adult male rape survivors. However, the researchers approached the issue of access to justice from the understanding that sexual violence disproportionately affects females.

Quoting statistics from the National Crime Records Bureau, the report states that India’s cases stood at 32,033 in 2019, down from 33,356 in 2018. However, it also highlights that this number is not necessarily indicative of the prevalence of sexual violence, as most cases remain unreported. Livemint’s analysis of the National Family Health Survey 2015-16 data revealed that around 99.1% of cases go unreported in the country.

“Underreporting of sexual violence and abuse is a major problem throughout South Asia,” Srinivasan explained. “Victim-blaming attitudes still remain extremely prevalent, whether from women's own families, community members, or even amongst justice system officials. The stigma faced by survivors and the fear of being blamed for their rape are some of the major factors contributing to either delayed reporting of cases by survivors, non-reporting of rape cases to the police, or survivors deciding to drop the criminal case after it has been filed.”

The report further highlights that non-reporting is highest among women from socially excluded communities as they face intersectional discrimination based not only on their sex, but also their caste, ethnicity, tribal or religious identities.

When it comes to protection gaps in laws, the report flags the limited legal definitions of sexual violence in two out of the six surveyed countries. Even in India, which is considered to have a relatively accommodating definition of rape, laws continue to frame sexual assault as a crime of morality by using terms such as “outraging” or “insulting” the “modesty of a woman.”

“A major gap in India’s rape laws is the failure to provide protection to victims of marital rape,” stated Srinivasan. Despite women's rights organisations demanding the legal recognition of marital rape, four of the six countries studied continue to permit marital rape of spouses over 18, the report claims.

In India a 2017 Supreme Court judgement criminalised marital rape of minors between 15 to 18 years of age. However, marital rape of adult women is still legal, making India one of 36 countries that have yet to criminalise this act of violence.

“Ensuring that marital rape is criminalised would make justice more accessible for all women, irrespective of marital status. It could also send a powerful signal that a woman always has the right to choose whether and with whom she has sexual relations,” Srinivasan said.

All six countries reported instances of victim-blaming and discriminatory attitudes towards survivors. Deep-seated gender biases further affect the impartiality of the investigation. The report reveals instances of violence from officials, as in the case of one survivor from India who said, “I was slapped twice by the SP (Superintendent of Police) on my cheek, blaming me that it was my fault and I was lying.”

In India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Nepal, police officials were commonly found refusing to file complaints or delaying the registration of an FIR. Long delays were reported in conducting the medical examination and trial as well.

India imposes a time limit of 60 days for filing a chargesheet in cases of sexual violence. It also has the strictest time limit of 60 days for conducting rape trials. However, the stakeholders interviewed stated that this timeline was almost never followed. A 2017 study on rape trials found that simply recording the rape survivor’s statement took 8.5 months on average. In 2019, some 89.5% of rape cases were still pending trial at the end of the year.

Similarly, while Indian law requires the medical examination to be conducted within 24 hours of receiving the complaint, one survivor stated that it was not conducted till four days after her complaint was filed.

In many countries studied, including India, the traumatising “two-finger test” is still being used as part of the medical examination. The test, which requires the examiner to insert two fingers into the vagina to check whether the hymen is broken, was banned by the Supreme Court in 2013. However, survivors claim to have undergone the test despite the ban.

“Many survivors of sexual violence face a further ordeal when dealing with the criminal justice system. Impunity for offenders must be addressed, and the response of police and prosecutors to sexual violence cases needs to be drastically improved. This includes better police accountability, improving implementation of victim and witness protection schemes, and improving access to support services for survivors,” Srinivasan told The Citizen.

“Action needs to be taken against medical professionals who continue to perform the two-finger test, and community intervention in cases of sexual violence should be limited,” she added.

There is also a severe problem of corruption, which was found to be most acute in India and Bangladesh. Survivors are forced to pay bribes in order to have their complaint registered. In many cases the police demanded this bribe themselves, the report claims. Often, the police filed counter-cases or criminal allegations against the survivors, believed to be the result of bribes or pressure from the perpetrators.

Even healthcare professionals have been accused of taking bribes to falsify results of the medical examination in favour of the perpetrator.

The added pressure to enter into extra-legal settlements with the perpetrator is another major issue in India, Bangladesh and Nepal. The report states that 60% of the 22 survivors interviewed said they were pressured by the perpetrator, his family or community members not to file the complaint or to drop the case completely.

“When it comes to access to justice, the frequency at which survivors are pressured and threatened by accused persons, their families and community members (including panchayats), and thereby forced into compromises is extremely alarming,” Srinivasan stated.

“It is also concerning that justice system officials, including police officers, prosecutors and judges, often encourage such extra-legal settlements,” she said, adding that India must follow in Nepal’s footsteps to address the problem of compromise in cases of rape.

Nepal passed an ordinance in December 2020 imposing a sentence of three years’ imprisonment and a fine for those who force mediation or reconciliation between rape victims and perpetrators, or their families, Srinivasan explained. Individuals holding public office who try to mediate face more stringent penalties.

While fast-track courts have been set up in India, the report claims these have done little to speed up the process of trial, while many Indian states have chosen not to set up fast-track courts at all. Where fast-track courts do exist, crime statistics show that over 80% of trials took over a year to complete, and nearly half took over three years.

Low conviction rates further erode trust in the criminal justice system. The conviction rate for sexual violence cases in India was 27.1% in 2019. The report also makes a case against the death penalty, introduced by India in 2018 in cases of rape of children under the age of twelve. “Given the extremely low conviction rates in rape cases, what is important is the certainty of punishment, not the brutality of it,” the report states.

The researchers also consider what justice means from the perspective of survivors. They found that survivors’ idea of justice includes speedy trials, increased sensitivity and accountability from the system, timely procedures, conviction of perpetrators, and changing the victim-blaming attitudes of society.

The researchers further recommend addressing the protection gaps in laws, improving police responses and prosecution procedures, and ensuring survivor-friendly medical examinations as means of strengthening the legal provisions and implementation mechanisms in these countries.

They also suggest various ways to design holistic interventions, such as allocating more funds for sexual violence prevention and response programmes, improving data collection on reporting and convictions, and increasing efforts to align justice to a survivor-centric approach.

According to Srinivasan, an integrated approach is key to addressing the gaps in the criminal justice system.

“The recommendations in our report about changes which governments need to make are based on the realities faced by women and girls who have been raped,” she said. “In order to make the improvements urgently needed to end impunity for rapists, it is vital that governments understand and acknowledge the experiences of survivors.”