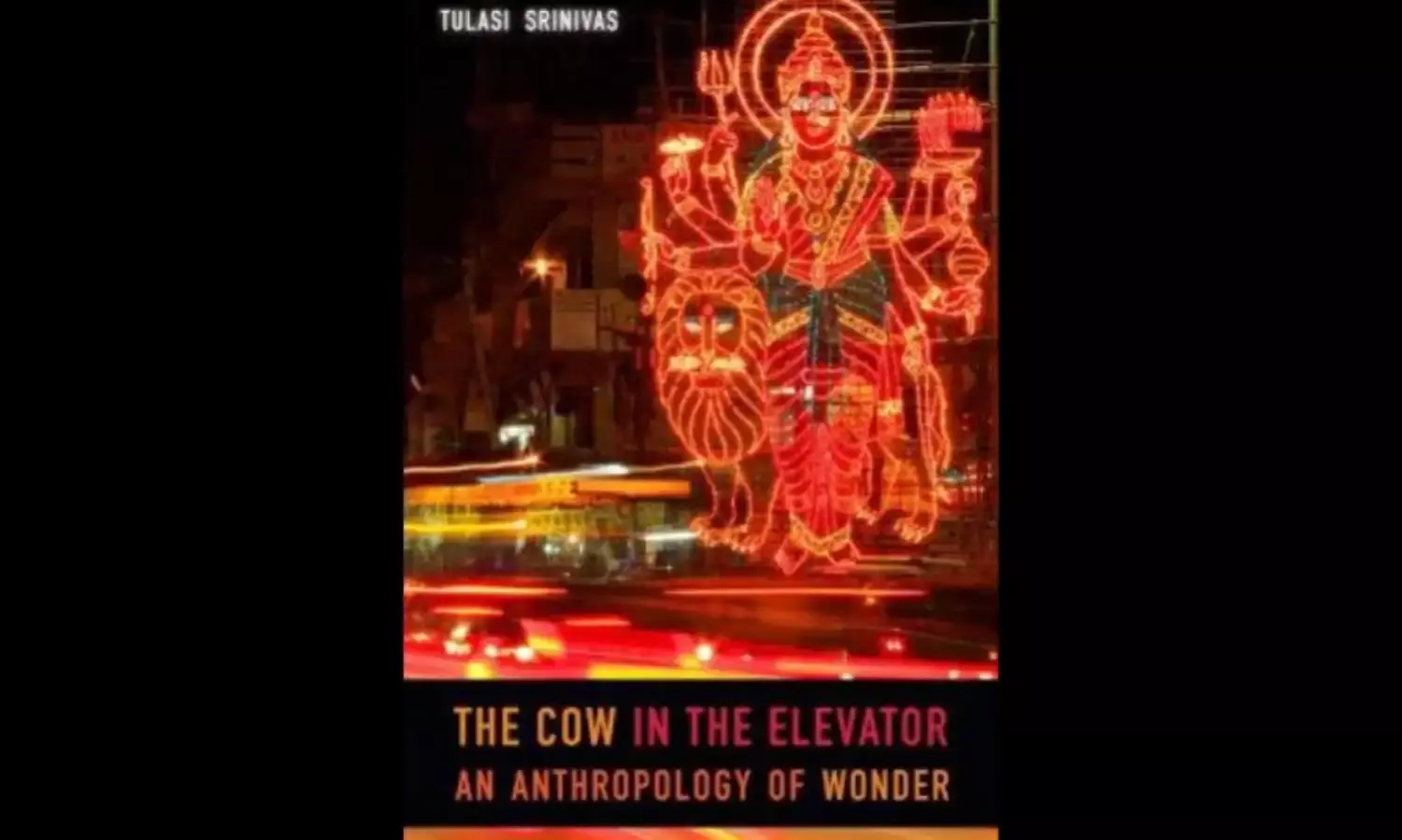

“The Cow in The Elevator”

Book Review of Tulasi Srinivas’ 'The Cow in The Elevator';

If you are an anthropologist, it is very likely that you have chanced upon the work of Tulasi Srinivas. I first read Winged Faith when I was a curious observer of guru movements, Curried Cultures for an anthropology conference, and a smorgasbord of her papers thereafter. COWEL (as Duke calls it) teased me into questioning what Srinivas has so beautifully and chillingly thought through for decades—wonder as an ethical practice.

Indeed, the book seduces one into thinking that wonder is borne from the intimate connections between religion and the outer self, and her claim that wonder is in everything that gleams reflects in her eloquent, in-depth, and ethnographic account of the book's main character—Bangalore.

Incredibly textured with Srinivas' quirky and complex narrative of her and her fellow travellers' escapades, and her funnily dry scholasticism, it holds its promise as a guide to the religious realities of the neighbourhood of Malleshwaram as well as a cartography of the city's social history.

Srinivas notes that the technocratic affluent adjust to fast-paced lives by negotiating their religious responsibilities as devotees of god. In their quest to understand the modern world, they take part in temple practices to bolster their faith in Hinduism whilst simultaneously challenging themselves to excel in their professional lives at home and abroad.

This reminds one of Smriti Srinivas' earlier work on Bangalore, but COWEL is the latest version that acutely and accurately documents the crumbling context of a city of traffic jams, endless waiting, religious festivals, and a crucial component of Karnataka politics: the tensions and cultural realities of the Tamil diaspora. Much is said of the "boomtown bourgeoisie" and how they receive their prasadam (sacred offering). Their appetite for the high life is construed as the very nature of this nauseating and dangerous city.

The idea of waiting as expounded by Srinivas deserves a special mention as she devotes an entire section to it. Nancy Scheper Hughes herself wrote in the 90s that "watchful waiting is what all anthropologists are best-trained to do." Srinivas is a 'waiter' in this book, constantly grappling with the materiality of Hindu temple life in one of the city's oldest and orthodox spaces, and receives the darshan (sacred seeing) of the Lord only to realise that the Lord has gone animatronic.

Flashlight Divinity could have been an alternative title; but suffice it to say, COWEL is a delectable and eminently readable book where "deities jump fences and priests ride in helicopters" (as the blurb on the back cover magically and succinctly puts it).

Let's face it—Srinivas is neither a seeker of liberation from the cycle of birth and death (Sanskrit: moksha) nor a flag-waving rationalist. Her homies, or informants, have been the priests of a Malleshwaram temple who have afforded her a perspective that has made her aware of the problems of creaturely life. She demonstrates that if wonder fails the imagination, much is left to be desired in the world today.

The end is rather touching, for the chief priest whom Srinivas has conversated with for so long, dies in a traffic-related incident. She is quick to mesmerise the reader by offering a nuanced, assiduous, and creative rendition of wonder that reads somewhat like the Lalitha Sahasranama authored by Amanda Jean Lucia, Lawrence Babb and Karl Marx, dissecting her own autobiography along the way, forcing her to contend with the notion that she was in a deeply ancient zone where her modern raiment was ridiculed as not upper-caste enough. By whom? The male priests and the women folk who thronged the inner sanctum.

The juxtaposition of the ethical is wedded to the title (given to her by fellow yankee anthropologist Kirin Narayan) where the cow (representing nostalgia, the past and even desire) is hauled into a space without consent, into a mode of transportation mostly seen as belonging to humans and dogs, where a boundary is created between who enters the elevator and who cannot. Srinivas' reading of the temple is that like the function of the elevator in which not everybody is welcomed, the elevator denies entry too. Her fierce critique of caste comes out at a time when it is most needed.

COWEL serves as a useful guide to explore the inner entrapments of Srinivas' intellectual mind focused on a city on the edge of an infrastructural precipice, and which she knows not only adjusts to the different linguistic communities of India but also to its own plethora of caste, gender, and class divides.

Whilst the book can be a dictionary's nightmare to some, it certainly has a sexy title and a sexier lens through which globalisation, neoliberalism, and technology are implicated in the everyday and habitual universes of experience and capitalist spirituality. It was hard not to devour it in one go.

Like all books, it has a great ending that touches the head and heart, making it readable not only for heavy-duty academics but also for children who are interested in South Asian heritage.

I warmly recommend it as a gift for your loved ones this Independence Day. As India turns 71, its netas need a wakeup call. You could either read the book to know what Srinivas thinks of Modi's atavistic longings, or to gape at her non-academic citation (she quotes Obama), or to simply marvel at the maze of thought that has gone into writing it. I did all three, and enjoyed the climax thoroughly.

(Dhruv Ramnath is pursuing a Master of Arts in Social Anthropology at the School of Oriental and African Studies)