Uttar Pradesh (UP), the country's most populous and poorest state is caught in a raging storm over language.

Urdu has been denounced as a language of fanatic Muslim clerics in the state assembly by none other than Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath. The CM made it clear that he has no time for Urdu.

Today the proceedings of the assembly are allowed in Awadhi, Bhojpuri, Braj, Bundeli, as well as in English. However the CM lashed out at the leader of opposition Akhilesh Yadav when it was suggested that Urdu should be included in the list of languages allowed expression in the state assembly.

Those who know better were quick to point out that Urdu is not the language of a religion. It was born on the streets of different parts of the country and in the lap of ordinary citizens. A long list of names of non-Muslims was quoted including that of Pandit Ratan Nath Sarshar, Munshi Jwala Prasada Barq, Munshi Premchand, Tirbhun Nath Aijir, Firaq Gorakhpuri and Gopi Chand Narang who had spent a lifetime working in Urdu.

Urdu is loved as a language of passion, poetry and patriotism.

In a conversation with The Citizen, the London-based author Noor Zaheer compared language to a river.

Quoting a Kenyan saying, Zaheer said that a river survives if it flows but it lives when refreshed by tributaries. What an apt description of the difference between surviving and living. A language is comparable to a river as it gushes down often to formulate itself, at other times it detours to overcome obstructions, placid, and solemn, allowing space for expansion of thought, running into whirlpools to churn ideas and philosophy. Any living language is continuously flowing, its users exploring its journey, making their own contribution to what might be called a personal trek but what remains essentially the voyage of the language like a river.

The seed of Urdu was sown in the country by the Indian literati that was weary of using Persian to express powerful emotions. Comfort lay in the use of local dialects and vocabulary, metaphors and idioms exchanged with loved ones in the family.

Besides literature penned in Urdu had resonated with the local population at large. The lure was to use a language that could be understood and appreciated across the country, and not just by the literati.

Delhi had suffered political unrest throughout the 18th century, making people flee eastwards in large numbers. Awadh was a haven of peace at that time. The craving for azadi by the rulers of Lucknow from Delhi made them eventually secede quietly. There was no violence involved in the breakaway of Lucknow from Delhi, a city preoccupied with defending itself from attacks by Persian and Afghan warriors.

Meanwhile the independent kingdom of Awadh came into its own, generating its own revenue and free of the shackles of Delhi politics and linguistic constraints. The peaceful coup by the rulers of Lucknow became part of the collective psyche of the population. That healthy rebellion became a way of life and seeped into every aspect of life from cuisine, clothing, music, dance, language and poetry. Space was found for numerous trials and tests and creativity was encouraged. Soon the novelty of imagination and ingenuity were absorbed into the cultural structure of the entire region.

The new found freedom patronized by the rulers benefitted the Urdu language most. The strength of the Lucknow rulers was the relationship that they had forged with the local population of Rajput, Kayastha and Khatri. Together the friendships helped the economy to boom and cultural activities to thrive.

Urdu had opened itself to the dialects spoken in the surrounding regions of Lucknow. Proverbs and idioms in the dialects of Awadhi, Purabi, Khadi Boli, Braj Bhasha and Bhojpuri flowed into Urdu as did the appreciation of the rhyming couplet doha and the quatrain verse of chaupai both ancient and important forms of expression of Hindi poetry. The fearless encounter between different cultures also roped in legends, myths, parables and fables that laid the foundation of Urdu prose.

The language which blossomed in Lucknow bred cultural integration across religions, caste, class and gender. In a very short span of time, Urdu developed a freedom of expression that is found only in the free-flowing language of the masses. Lucknow became the melting pot that valued spirituality as much as sensuality. Perhaps the most insightful example of fusion of the physical with the mystical is the evolution of the performing arts. Kathak, Thumri, Dadra, Chaiti and most specifically Qawwali, that had been in existence since the 14th century from the time of Amir Khusro, now came into its own in Lucknow.

As Lucknow catapulted in the 19th century into a world class capital city, Urdu no longer remained just a literary activity. It became a way of life of all citizens. It was a tool to gain manners, an instrument to practice etiquette, a device to indulge in spirituality and a weapon to cut the rival to the core with an imaginative use of words woven into verse.

For both the prince and the pauper, the courtesan and the chef, affluent shop owners and roadside vendors, street singers and eunuchs had together contributed to build a community where aesthetics was appreciated and repartee rewarded.

There was a time when the rulers of Lucknow had made sure that life in Lucknow was not just lived but it was celebrated. The inclusive and open way of life had helped the Urdu language and poetry to bloom like an endless season of Spring. Zaheer pointed out that in the last decade or so she has come across writers of other languages imbibing the formats of meter and verse of Urdu into their own language of expression.

“It is not surprising to come across a ghazal in Marathi, Gujarati or Tamil in contemporary poetry. The most recent addition has been ghazals in Sanskrit,” she said.

Recalling an incident from her childhood, Zaheer said that during one of the ten-year census collections a volunteer had asked her parents if their mother tongue was Hindi or Urdu.

Her father the well-known freedom fighter and author Sajjad Zaheer replied Awadhi, while her equally famous author-mother Razia, spontaneously said Marwari. The strong bond and commitment of the two important writers of Urdu could not bypass their love for the dialects, the tributaries that had enriched the river of Urdu.

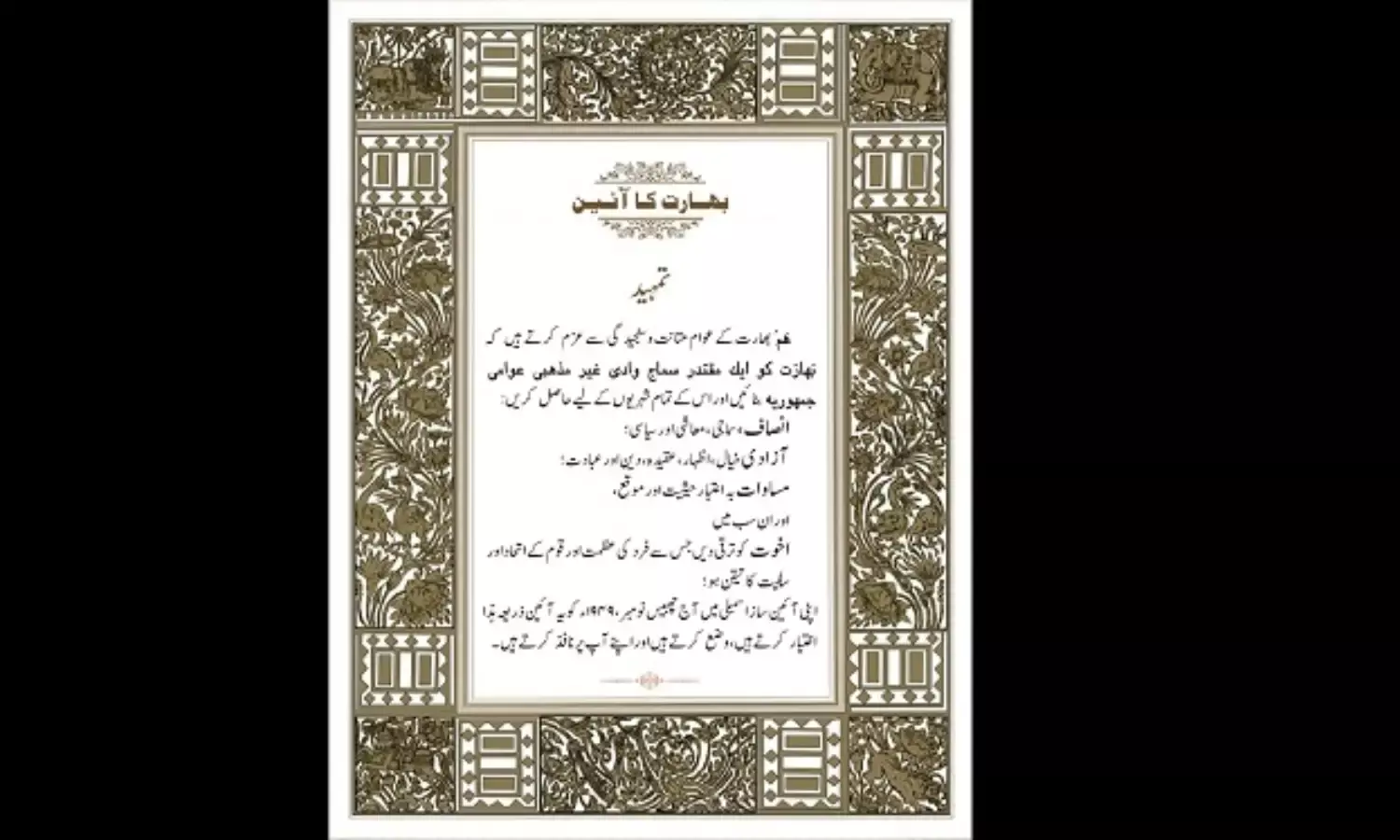

Therefore, Milord it is most incorrect to sieve Urdu away from the local dialects of Awadhi and Bhojpuri or from the people on the street. Worse is to ghettoize the language into the arms of one religious community as Urdu is the love of all Indians.

Mehru Jaffer is a writer and author. The views expressed here are the writer’s own.