Counting Caste: Rethinking Majority and Minority

Breaking the caste census deadlock

A two-day conference hosted by Oxford University called ‘Counting Caste: Breaking the Caste Census Deadlock’ began with a keynote address by Sonajharia Minz, scholar and Adivasi rights activist, who is vice-chancellor of the Sido Kanhu Murmu University in Dumka.

Minz invited the panelists and audience to ask, what is development? And with the example of the Millennium Development and Sustainable Development Goals promoted by the United Nations asked, “Are these goals unrelated to the caste census?”

One of the first vice-chancellors of an Indian university from an Indigenous background, Minz took the example of Tamil Nadu, which has a 1% Adivasi population. If the development and economic indicators are working fine for the remaining 99%, is it acceptable to us that they are not working for the Adivasis? “This is the kind of qualitative question I am looking to ask. And not looking for quantitative answers.”

The first panel, titled ‘Rethinking Majority and Minority in India: The Question of Caste Census’ was moderated by Asha Singh, who teaches gender studies at the CSSSC in Kolkata, and comprised journalist and editor Dilip Mandal, DMK MP Kanimozhi Karunanidhi, sociologist Satish Deshpande, and trans rights activist Grace Banu.

Asha Singh, whose research is on “the category of Other Backward Classes and its limitations and possibilities, especially concerning gender,” began by saying that “the need for a caste census is well established in our minds.”

She said a census must include every individual, is never complete without publication and dissemination, is a public document, and only the state possesses the capacities for such an exercise.

Of the various census categories used in the colonial period, she said the “Upper Caste allies of the colonizer were surprised to find out the rest weren’t willing to accept their notions of hierarchy.”

And described the void in contemporary India, where “in the absence of modern integers for concrete politics, we hark back to mythical times,” making arguments “which can’t be disputed in any intelligible fashion.”

Dilip Mandal argued that it is no accident that Independent India has never had a caste census in the public domain, and that when it is conducted it must be part of the decadal census under the Census Act.

“I suspect there must be someone in the country who doesn’t want the reality of caste demography to emerge. So who is it who is not ready to reveal the certainties or uncertainties of such an exercise?”

“Such census exercises are not strange to other countries – race and other demographic categories; India collects data on religion, language, gender, kacha/pakka house – but caste has been some sort of enigma for policymakers, they just don’t want to have caste data.”

Mandal emphasised that “caste enumeration not a novelty in india. Since 1878 (1881 was the first synchronised census) caste was included in every census before independence, and it is common practice to enumerate the diversity of socioeconomic disparities and all the other factors in society.”

As an example he observed that the “Modi government this time has released the 20th livestock census, we have those figures, we’ll know the numbers of cows, goats, pigs, yaks, camels, horses - almost all other domesticated animals.”

“Why is the government collecting these data? To frame policies. Policies should be based on data, it gives deep insight actually, and statistical data helps the government inform its policy – but this is not the case with Indian citizens, they are not counted with all categories.”

He said the identity of the census enumerators also remains a mystery, although the United Nations model census “suggests collecting comprehensive details for all communities and for census collectors - which is not happening in the case of India.”

Mandal pointed out that the caste blind spot is selective. “We do always collect data pertaining to SC and ST, and religion, language, all that, but we don’t collect data for certain categories, that is especially OBCs and oppressor caste, upper caste, raised caste, Savarna caste…”

On the need for these data, he said that our fundamental rights in Article 16-4 of the Constitution for instance require the state to give backward classes reservation in state services, provided they are not adequately represented.

To know whether they are adequately represented “we need two sets of data: their total number, and their representation in certain services or jobs… without these two we can’t say if it’s underrepresented or overrepresented. So you can understand what sort of problems we are going to have and are facing because of not having caste enumeration.”

Mandal described the recent political history of the caste census in India.

“This issue came up early in ’77-78 and the demand for a caste census came to the fore during the Mandal commission report. The introductory chapter says we are depending on the 1931 census, and we will have such problems in future also, so we are suggesting and recommending that in the next census the Government of India should conduct a caste census. This is part of the Mandal commission report.”

“The government had the opportunity to conduct a caste census in 2001, it was possible, because Deve Gowda in ’98 passed a Cabinet resolution that in the next Census caste will be enumerated. Then Vajpayee in 2001 decided not to have it, when Advani was home minister, they just did not follow the Cabinet note of the Deve Gowda government.

“So BJP has some problem with caste census: this will be for the second time that they are scuttling it. Though the Congress has its own share of problems, because the next opportunity was in 2011… Lalu, DMK, even Mulayam and Sharad Yadav, they all supported caste census and a consensus was there in Parliament, and Manmohan Singh made a commitment on the floor of the House that in 2011 caste will be enumerated.

“But the PM played his own game, he was chair of the Group of Ministers and he decided to conduct it separately, not under the Census Act of 1948. So after that the special Socio Economic and Caste Census of 2011 was exercised with frugality, and after spending 4,893 crores we don’t have any data related to SECC 2011.

“One fine morning in 2015 Arun Jaitley as law minister organised a press conference to say the SECC is not providing any reliable data, and there are 9 million mistakes in the data, so he formed an expert group under the chair of Arvind Panagariya… but Panagariya left the government in 2016 after demonetisation and rejoined his teaching job, so we don’t have any data after spending 5,000 crores on SECC.

“This is the brief history of census and caste census which we still haven’t conducted yet. And in 2019, remembering, Rajnath Singh, then home minister, promised that OBC census will be done but that was because of the OBC vote actually, and Modi was pitching himself as an OBC leader, but now his government is saying that caste enumeration is not under their consideration.”

“We are relying on 90 year old data to formulate policies at this juncture, and if we miss this year it will be 100 year old data, and it will cause so many problems,” Mandal explained. “We in India have numerous policies based on caste so it’s always better to have caste data.”

“I don’t understand what is the problem and why certain classes of people are afraid of it. What sort of data are we expecting, what uncertainties are they afraid of?”

He concluded with the problem of castelessness, suggesting that the Indian state is not conducting a caste census because of “castelessness and caste blindness, and how the Upper Castes actually use castelessness as strategy and tactics to hide the hegemonic structure. So I am leaving that part to Satish Deshpande because he is the expert and started the dicussion on this topic.”

In the absence of accurate caste data, said Mandal, the Union and State governments are making grants of public money for “OBC development” and other redistributive measures, without knowing the number or economic status of OBCs and other groups.

There is also the “problem of many social groups asking for OBC status”, which is given or denied without knowing whether the community is over or underrepresented.

Even the quota for Economically Weaker Sections instituted by the Modi government lacks empirical backing, he said, to the unfair advantage of the non-SC, non-ST, non-OBC beneficiaries.

“Why is the EWS quota of 10% not 12% or 7%? In many states the category might even be 3% or 2%… but still they are getting 10% in many of the states.”

Mandal emphasised that the caste census “should be the same as the decadal census, and under the Census Act”, and that the “states can’t do a census because it’s in the Union List in the 7th Schedule. So states can do caste surveys but can’t conduct a caste census. That’s on the Union government.”

DMK MP Kanimozhi Karunanidhi began by saying that a caste census has been “the demand of the DMK and many UPA constituents for a very long time… maybe the numbers they saw was not a very happy one so it was not made public.”

“We hear arguments that it might rekindle caste feeling, people might use it politically, but we cannot hide that caste plays a major role, like religion,” in India. “And gender bias is there, we cannot hide from these things.”

“There is nothing that happens without caste. The candidates even for local body elections, sadly the fact is you cannot decide your candidates without considering which caste the majority of people living there belong to. No party can give out a list of office bearers without considering which caste, what representation, who’s being left out and who included, this is the sad truth,” she said.

Kanimozhi defined the “so-called upper castes” as “the castes which do not part with power.”

She drew a parallel with the women’s reservation bill, “that is supported by everybody but has never been passed by Parliament. Nobody wants to give a powerful space to women, political power and decision making opportunities, we do not want women to be part of such an important debate.”

This is because “there are forces today which have become very very powerful. Not overnight, they have been there and entrenched and very powerful, and behind the scenes and not in the limelight. So powerful, they can stop, change, stall policies and processes which will actually bring justice to the majority in this country which deserve it.”

“Without this census we can never understand what the truth is or the distance which we need to cover.”

Delhi University sociologist Satish Deshpande began with the words majority and minority. Besides their numerical or proportional sense, of “different kinds of maniness or fewness”, he said they had come to acquire further political connotations, such that not every kind of fewness leads to minoritisation, and vice versa.

According to him this meant that these words were “at the end of their semantic journey.”

Calling the majority that which has a “claim to or actual possession of different kinds of capital, if you like,” Deshpande proposed to look at the census as a collective self-portrait, and caste as a web of distributional relations.

“The caste census is going to be an important step towards the annihilation of caste, a destination that has eluded us so far,” he said. “The state’s being caste blind has not worked at all, in fact it has worked in favour of the reproduction of caste inequalities in modernised, even harder to get rid of, even more stubborn forms.”

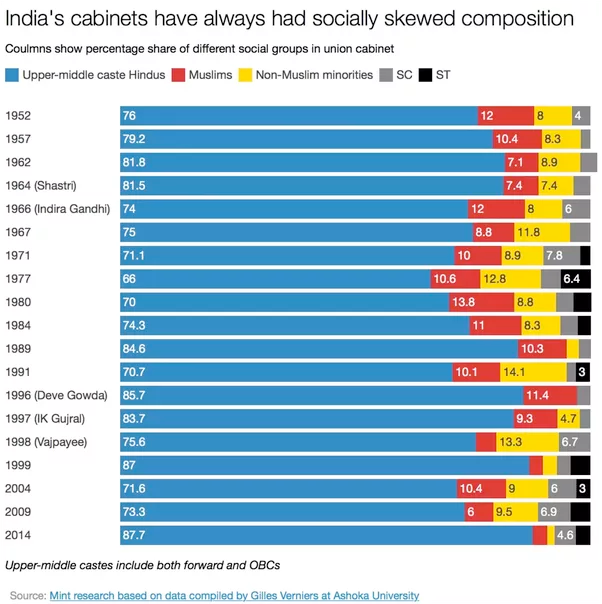

Deshpande observed that the “dominant common sense has presented it effectively that caste only means Lower Castes, like gender truncated to women and so on.” This “helps to make Upper Castes as castes invisible in our society - and so their disproportionate share over national resources is also invisibilised.”

“The journey towards transcending of caste will have to pass through caste, that is to say will have to count caste, recognise the many inequalities that flow from it, the very sucessful ways in which it has managed to reproduce, how caste hierarchies have managed to reproduce themselves,” he said.

Therefore it is important, “before we arrive at that destination”, to talk more about caste, acknowledge its presence, count it wherever it is relevant. This is preferable to “silence, a policy the state has followed for a long time. And we’ve seen what that has produced: the claim to castelessness in certain contexts has been the most disabling of things in our fight against caste inequalities.”

“How to get people to acknowledge their caste?” Deshpande asked.

He replied that it doesn’t mean that you acknowledge casteism, but that “you are a historical product of a particular system - not that you subscribe to it necessarily, or that you benefit from it today - the point is to recognise social origins, the continuing significance of caste - particularly for those who are enabled precisely by the benefits of caste to feel the luxury of feeling that they have no caste.”

He said that only people of some castes have that luxury today, and there is no better way for everyone to begin acknowledging that they “have caste” than to do it in a census, a collective self-portrait.

He described the “enormous amount of effort goes into handling the raw data regarding work - it is similar for languages, religion, a lot of raw data, thousands of religions that people say they practise, and the over 17,000 languages spoken in India… but most of all the enormously complex occupational data or work data is handled successfully ultimately by the Census.”

He said the digital technologies available today mean that “it is possible to count caste, the developmental reasons are important, how it will help us in understanding the distribution of national resources, where different communities stand, and adjusting our development programmes.”

“But to my mind the decisive argument is that we have to get every Indian to acknowledge a historical embeddedness in caste. We must not allow any Indian to say that they have no relationship to caste. Even if they are given the option of saying that they have no caste, this option should be solicited: they should be asked the question of what their caste is.”

This option he said is unavailable to most people anyway. “To the vast majority, the world is continually telling them what caste they are.”

The last speaker was Grace Banu, a Dalit and Trans rights activist, whose discussion of the “double oppression of caste and gender” was followed by responses from the panelists.

Banu described the growing category of non-cisgender, non-binary people recognised in official India, as the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act of 2019 as well as the Supreme Court’s Nalsar judgment in 2014 (recognising a “third gender”) together include sociocultural communities and intersex people, besides transgender and transsexual human beings.

While the 2011 Census counted 4,87,803 Indians of the “other” gender, she said, that number is inaccurate and an undercount, because in 2011 very few people recognised that genders are not binary, and sex is not gender.

“In 2011 we faced too much transphobia and discrimination, so in that census they considered all trans people in the male category. That is a completely transphobic ideology… so many trans people are there but we didn’t have a proper census.”

“Now we are in 2022, there is so much more visibility, trans people came out, etc. The Kenyan census counted intersex people in 2019. Our census officials should at least consult the trans and intersex community before any kind of census.”

“But where is the gender sensitive training of the enumerators?” she asked. “People having casteism and transphobia - how do we create a sensitive training for them, and give the training to those kind of people?”

Banu questioned the focus on majority and minority when there are so many people who simply aren’t counted, by a transphobic state manned by cisgender personnel.

“How are we the majority or minority when we don’t even exist on any of your data? Most government and research data continue to be binary - public health, higher education statistics, labour force data - continues to be a binary kind of data, it completely excludes trans persons data.”

Similarly the university discourse has focused exclusively on trans bodies, rendering it useless to trans people.

“The research community is completely transphobic. Their research always focuses on the body and never opens the larger socioeconomic debate. All the research people are all cis people and they all want to know about my body and where I am coming from and all that kind of data – other than that it doesnt give anything of impact to the trans community.”

For this reason the caste census could only be seen as a starting point, in “revealing a process of recognising and identifying newer marginalities. Caste census is not a debate, it’s the starting point of a process. It’s identifying a newly marginalised community of people like intersex community people.”

And just as caste society is scared of the caste census because of the word reservation, said Banu, trans society is confronted with “horizontal reservation.”

“Another word for trans society to be scared of, horizontal reservation. The Union government is willing to put all trans people in OBCs… but this is completely against the reservation policy and completely against equality.”

Despite years of educational efforts, Banu said that Indian officialdom still does not understand what to do with trans people. She described how in Tamil Nadu after the Nalsar judgment, the state government gave trans people with caste certificates the right to access those reservations. “But people without caste certificates, you are automatically considered MBCs,” or most backward classes.

She pointed to the gazette notification “showing so many caste lists, in that MBC 36b or c should be transgender, eunuch, tirunangai, aravanis… For those people it’s a gender identity but they could be casteless.”

“This kind of diplomatic and critical knowledge people are there, and they don’t know about how to pronounce the trans people, how to handle trans people, how do we give the rights to the trans people – they don’t know in officialdom also – we have been educating them for so many years!”

Of the “trans friendly” DMK government in Tamil Nadu, Banu said that the State and Union governments ought to focus on rights-based schemes. “Welfare schemes are more important for oppressed communities… but rights also means education, employment, reservation rights, for participating in public space.”

This is important because of the “double oppression in the name of caste and gender.”

“Every day we are facing both kinds of oppression… so with vertical reservation like male > female > trans, but horizontal in the name of gender and caste. We need to give separate reservations for trans people.”

“So one new solution is to participate all trans persons in public space, the larger level space. We are demanding horizontal reservation, separate for the trans community, because only when we have human rights will all the trans community participate in education, employment, public space, political space, everything.”

Banu emphasised “focusing on welfare measures, but at the same time you should focus on our rights, because we want to live in society dignified lives, and we are also taxpayers of this country. More than 70 years our community people are doing begging and sex work, but we’ve paid our tax, in this so called democratic country, but we didn’t even get our rights: education, employment, reservation opportunities.”

Only with reservation opportunities would a caste census emerge, she said, calling it “the only solution to create a safe space for all communities’ trans people to participate.

“Jai Bhim, Jai Periyar, Jai Fatima, Jai Savitri.”

Dilip Mandal responded by emphasising the difference between caste surveys conducted by state governments and a caste census by the union.

“You can be tried for giving wrong data, and the enumerator can be legally somethinged for providing wrong data under the Census Act. States can do so, their enumerators have local expertise, but it needs to be under the decadal census for data to have sanctity under the Census Act.”

“Why are they afraid?” asked Asha Singh.

Satish Deshpande said “I can start,” and concluded that performing a caste census would be difficult for a variety of reasons.

Singh replied that some castes are already counted in every Census. “With SCs and STs there is always some amount of caste data in the Census, but it is OBCs and Upper Castes who are not counted. But what about the quality of information? We have minimal information on SCs, STs, trans people too – on the quality and content of information collected, how do we make the state accountable?”

Dilip Mandal agreed that “the purpose of a census is much more than headcount only, not just some numbers. And with new technology like artificial intelligence and big data analytics, if we correlate those 42 questions, you can have many sorts of data in real time. It’s not like when the Census was done in 28 days and tabulation etc took 5–6 years.”

“Now as the technology is there, and this time by conducting it on tablets and digitally (says the Census commissioner) it is not difficult to get all those correlations, about economic activity and sociocultural aspects, and migration and all those demographic data.”

“I think it’s more about having the intention to do it as it was done. But the data will be there for aggregation and correlation, I don’t think there will be a big problem… Even if I see the 1931 or ’21 Census, you can go and see in the library, you’ll find that those correlations have been done during the British period.

“So like you have data about Bombay state, that how many Brahmins have stated that English is their primary language – we have that type of data, so it’s not that difficult to have it in 2022 – it’s more about intention. How many trans persons are in which occupation, they live in what sort of houses, these correlations can be made, it’s not that difficult.”

Grace Banu concluded the discussion by talking about “data for dignity, not just distributional justice.”

“When the 2011 Census happens the government doesn’t even mention our gender identity. They put male, female and others, and they put the name 1, 2 and 9. So in Tamil Nadu when we say 9 it’s an abusive word for trans people… And after we raised the issues and we raised our oppression, they changed to 1, 2, 3… male first, female second, and transgenders third category. And now they’re saying based on the Nalsar judgement we are considering all trans people in the third gender category. Most states put trans in third gender.

“So when we say this thing gender, who is in the first gender? Do you have any Act, any clarification why you are the first gender and you are the second, and I am the third gender? So every time, why do you cis people have the decision authority over our rights? I have the right to say what is my identity. But always you people are giving the label, and I have to take it, because oh, you are doing it for me, and it’s a useful thing. But it’s not at all!

“You should know what is an ally. You are not our leaders. We don’t want leaders, we want representatives. So you should listen: what is our demand? This is our demand: the enumerators should know what is trans person, what is transphobic? How do we handle trans people?

“Your cis people thoughts – thinking of trans people as male – your thoughts are imposing us. We need sensitisation to enumerators on how to handle and how to pronoun the trans people. Every person should know and ask what is their pronoun? How do we mention them? So those kind of trainings the enumerators should have.”

“It’s like an excludedness that has happened to us. So all the time it’s people who are having transphobia and the caste system - only casteist people and transphobic people who are doing the census. So the government should give a sensitising work to them.

“Because it’s not our work, we are super tired, every day we have to educate all people. We have to educate patriarchal society, and within our own community we are having caste discrimination… People are thinking that trans people don’t have a religion, but it’s there in our community, caste is there in our community. Within our own community we are facing caste oppression, and we are facing gender oppression from civil society. So we need to consider that point of view.”

Asha Singh. “It shouldn’t be the burden of trans people alone. It should be the burden of state and civil society.”

Part 2 follows