Old But Gold - Documentary on Begum Akhtar

Zikr us Parivash ka

zikr us parī-vash kā aur phir bayāñ apnā

ban gayā raqīb āḳhir thā jo rāz-dāñ apnā

The translation of these two lines read as follows:

The splendour of her beauty and the manner I narrate

So my rival he's become, who was my confidant to date

These are the first two lines of a famous ghazal by Mirza Ghalib sung by Begum Akhtar and now, it is the title of an hour-long documentary on the Queen of Ghazals, Begum Akhtar directed by Nirmal Chunder. Zikr Us Parivash Ka won the 2016 National Award for Best Biographical/Historical Reconstruction. The film also won the Best Camera Award, IDSFFK, Kerala and Jury Award, IFFS, Shimla.

Nirmal Chunder is a dedicated documentary filmmaker whose earlier film Moti Baug based on the life of Vidya Dutt, a farmer living in the state's Pauri Garhwal region. The film was nominated for the Oscars. Nirmal Chunder has been making documentaries for two decades but his name became prominent mainly after Moti Baug made the rounds of several festivals and was nominated for awards as well.

There have been other documentaries on Begum Akhtar. But this one is the best mainly because it reaches far beyond the established parameters of a biographical documentary because it is almost a poem on celluloid rooted in a visually rich and melodious tribute to perhaps the most outstanding expert in the rendering of ghazals, thumris and dadras in the history of music in India and perhaps, beyond. ,

Produced by Sahitya Akademi, Zikr Us Parivash Ka, Chunder says that since the production house gave him a free hand to make the film in his own way, he decided that he would not make the film a simple biography but make it differently. “I took it as a challenge as the demand was to make a film on an internationally renowned performing artist who was no more and who I had not met in real life. I personally have no take on the film or about which genre it belongs to because the film is MY film but the reaction of the audience decides which genre they decide it belongs to. I am personally a great admirer of the ghazal form of music so this opened the windows wider for me when I set upon the research which was very demanding indeed,” says Chunder.

Saleem Kidwai helped him greatly during the process of his research. Kidwai was a Professor of History at Ramjas College, University of Delhi until 1993 and thereafter, an independent scholar who passed away last year.“Saleem Ji was a mountain of information of Kathak dance, on Muslim culture and of course, on Begum Akhtar,” informs Chunder.

The film opens on a frontal visual of the great Ayodhya Palace which invests the film with the ambience of forgotten history. “I wished to capture the historical fact that Begum Akhtar was a very widely travelled courtesan that took me to travel widely across the main places she lived and sang in from Faizabad to Lucknow, through Faizabad where she was born, Lucknow, then Calcutta and Bombay and Delhi. So, we travelled right across the country not just to visit the places but to internalise the ambience within which she grew up and her evolution as one of the finest singers in the country,” explains Chunder.

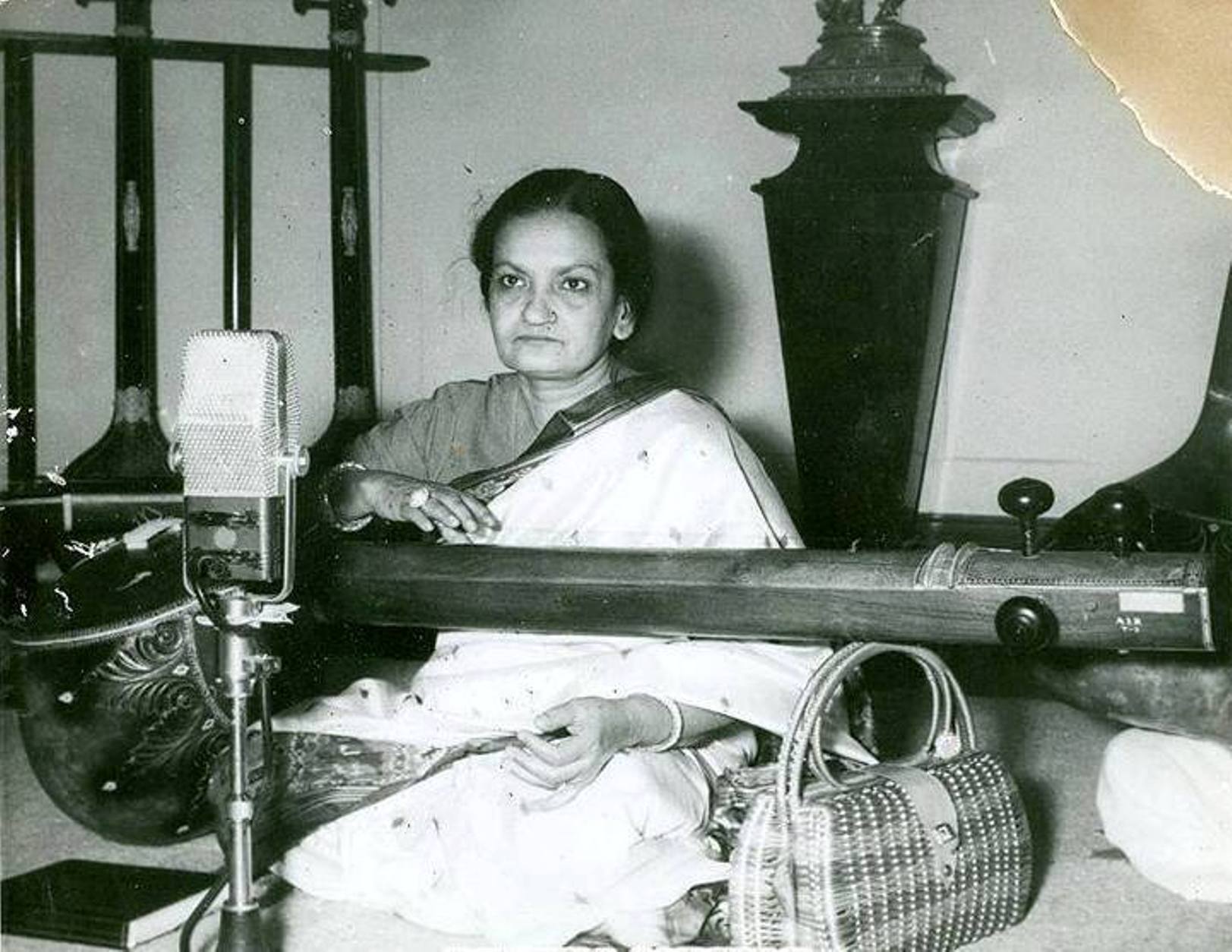

Begum Akhtar ‘s mother Mushtari Bai, a courtesan herself who was a consort of Asghar Hussain, a young lawyer, but was abandoned by him and Mushtari Bai brought up her daughter single-handedly, working very hard to give her daughter the finest education in music. They moved first to Gaya and then to Calcutta for her training in music. The film is replete with lovely Black-and-White photographs of the mother and daughter together which spells out the close bonding between them. It also has archival clippings of the singer talking in the office of the AIR thanking her fans and listeners for giving her the respect and recognition for her music.

Chunder has widened the horizon of the film by using music flush with the voice and songs sung by Begum Akhtar flooding the sound track as the main language and weaving in every form of visual art such as panning shots of Nature, trees, forests, river waters, ancient paintings, old photographs, film clips, and even around three beautifully executed Kathak performances by Ruchi Khare, interviews with eminent people who knew her well such as Pandit Arvnd Parekh who taught her the sitar for two-and-a-half years dotted often with the voice-over of Begum Akhtar narrating incidents from her life., then her favourite disciple Shanti Hiranand, who refers to her guru as “ammi” recalling how pain was an integral part of Akhtari Begum’s music. “She would cry inconsolably while she sang and it took me some time that these bouts of weeping were actually the backbone of her music.

Chunder is helped along the way by Ranjan Palit, one of the best cinematographers in India, who took creative and innovative care in allowing his camera to almost caress the locations he visited with his camera, ranging from the plush decorated place of the Ayodhya Palace through the faded walls of empty rooms, stained glass windows that had seen better days that tell us a great deal about the person who grew and evolved over time through them.

Chunder’s incredible research across all sources - media, archives, old recordings, letters, diaries, still photographs, movie clips, interviews, paintings, including a small diary in which she wrote down the telephone numbers of her friends and acquaintances and the first name in the diary is of Indira Gandhi makes the film one for the archives. Kidwai-ji also kept in his precious collection, recorded cassettes of her songs and the camera captures him fondly picking up a cassette and looking at it fondly.

Chunder has also fictionalised Begum Akhtar’s classical training as a child when she recalls that she would often run away because she did not like a particular raaga under Ustad Ata Mohammad Khan of Patiala Gharana and he once got very angry because she was not getting the raaga.

Begum Akhtar, then a little girl in pigtails, coaxed and cajoled and asked to be forgiven till he agreed. In Calcutta, she trained for three years under Ustad Wahid Khan of the Kirana Gharana. “I benefitted from his guidance and learnt from the devotion he taught me with,” she says.

A.K. Ghosh, owner of the Megaphone Company established in 1910 that began recording in 1930, says, “Many prominent artists have recorded for us. Begum Akhtar also did some recordings but her early songs were not very popular. Finally she recorded the number Deewana Banana Hai To Deewana Bana De which was a runaway hit and then her earlier songs also became popular and she never ever looked back.” The camera then cuts to a close-up of the jacket of the recording of the same song. By the mid-1930s, she emerged as a rising star in Calcutta, both on stage and in films and the shift to Bombay was imminent.

Vignettes of her life are described through graphics placed on the frame quite strategically that do not hinder the visuals. But Chunder skilfully steers away from the tragedies of her personal life and focusses on her growth as a singer repeating again and again, her slow but steady shift from being called Akhtari Bai Faizabadi, identified as a courtesan and the daughter of one, to Begum Akhtari when she got married to Akhtari Ahmed Abbasi in 1944, a barrister who studied at Oxford but did not object to her practising music.

But she restricted her music to public performances and stopped singing at private functions or mehfils as they were called then. She then stopped performing entirely because she must have felt that marriage did not demand a public performer in the family. She reportedly went into depression and came back into public life after five long years which not only rid her of her depression but also brought her back with a wider base in her voice and greater maturity in her performance.

Pran Neville, a scholar in the history and evolution of courtesans, Chunder says, “very kindly lent me his book Nautch Girls Of India: Dancers, Singers, Playmates (1996) and gave me permission to use the reproductions of a series of beautiful paintings of courtesans from the book and I used them prominently in the film when the camera lingers and wanders these women across the position of courtesans.” Shruti Sadolikar Katkar, a noted practitioner of Hindustani classical music says, “the contribution of tawa’ifs to our cultural and musical tradition is enormous.

They were trained in classical music and thereby, ensured its preservation. Many male musicians such as the tabla and sarangi players were supported by the tawa’ifs.” She goes on to add, “In concerts around 1912, these women could only perform while standing. They were not allowed to sit on the dias. Today, women like me who are practising and earning a livelihood through singing, can relate to the sorrow and the humiliation they must have felt. They must have felt that they are practitioners of a divine art but cannot sit while performing. Society has been very unjust to them. Begum Akhtar and her contemporaries were the last major tawa’ifs in our history.” This underscores that Begum Akhtar is culturally and historically very crucial.“ Says Saleem Kidwai in the film, “She epitomises the journey of a tawa’if who could reach only this far and no further.”

Though this film was made in 2014 and drew attention only after awards started pouring in, its historical and musical relevance makes it universal in every sense – time, language, culture, history and music.