Note Ban Plays Out, Voters Want Business not Communalism in Rohillkhand

#TCVotes:The upper castes vote BJP but together the SP'BSP will be hard to beat

NAJIBABAD, UTTAR PRADESH: Near the foothills of the Himalayas in a quiet corner of western Uttar Pradesh lies the region popularly known as Rohillkhand. About 200 kilometres northeast of Delhi and to the Ganga’s east, Rohillkhand is known for its highly skilled craftsmen and for the cultivation of sugarcane.

The craftsmen here perform a variety of fine work that includes wood carving, darning and metalwork. In rural areas sugarcane and mustard are grown extensively while mango groves cover other large parts of the countryside.

But both farmers and craftsmen are deeply disappointed by the policies of the government that have plunged them into a crisis. Two flagship decisions announced with much fanfare – the currency ban and the Goods and Services Tax – have hit all sections of the people here hard, with businesses yet to recover from the twin blows, even though two years have already passed.

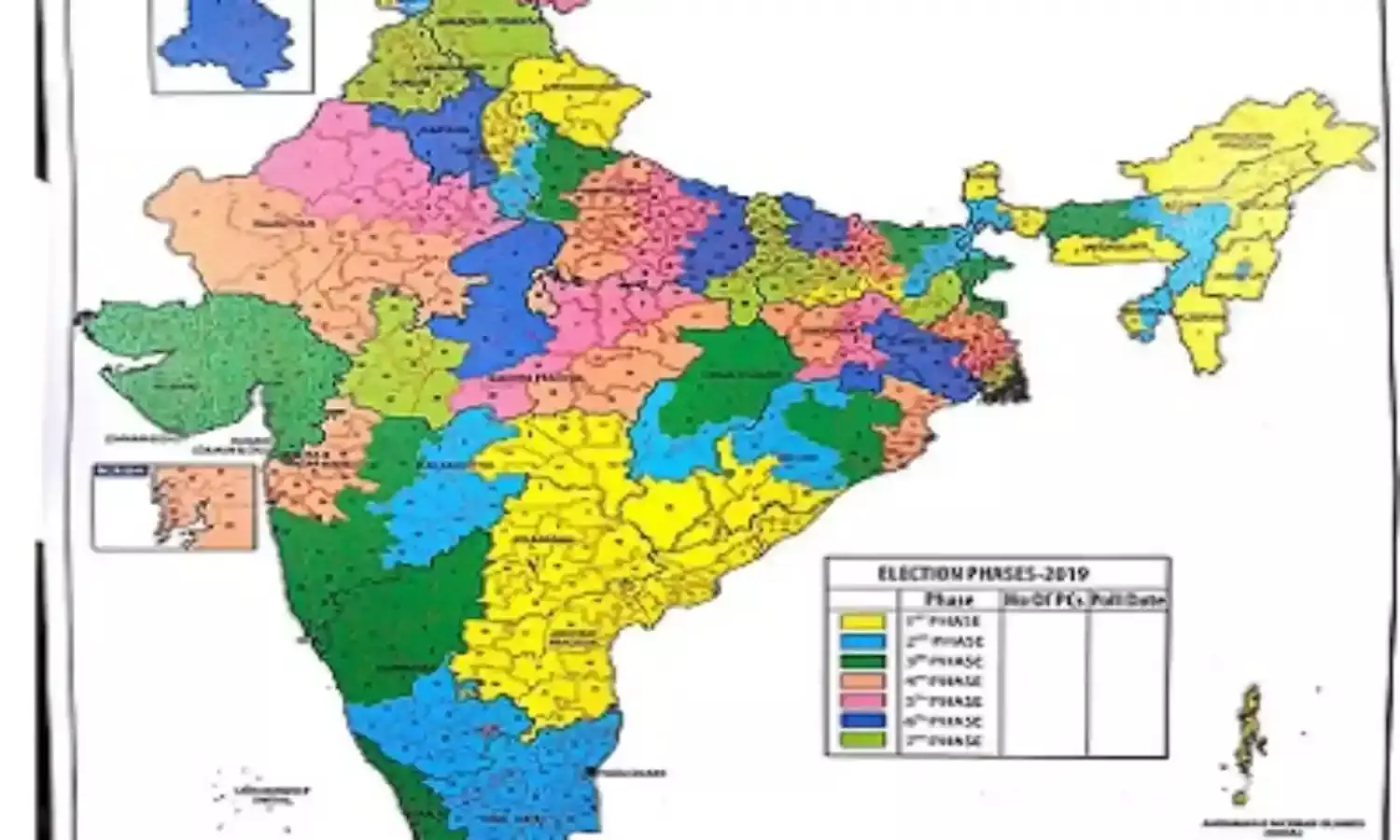

This area of Uttar Pradesh could pose a problem for the ruling coalition in the run up to the 2019 Lok Sabha elections; more so as the Bahujan Samaj Party and the Samajwadi Party have decided to join hands in the state. In 2014 the division of the anti-BJP vote played a crucial role in the good performance of the BJP. Both the SP and the BSP have a sizeable presence here and could together prove to be an insurmountable hurdle for the BJP.

*

Rohillkhand acquired its name from the Rohilla Afghans who settled near the Himalayan foothills on the invitation of an 18th century Mughal emperor, apparently to control the turbulent Rajputs of the area.

A fort called Patthargarh, with a storied history from colonial times, still exists about four kilometres east of the town centre. Its 20-foot high and 15-foot thick stone walls, with imposing gates to east and west, enclose a huge ground and a pond but not a single building. Most weekends find the ground filled with many teams of youngsters playing ‘gulli-danda’, played with a stick (danda) and a specially shaped small spindle-like wooden gulli that is used instead of a ball.

The carefree youngsters, who play for prize money of as much as Rs.2000, obtain their gullis from the skilled wood carvers of Najibabad who shape it from four-inch pieces of wood and sell them at Rs.8 per spindle. The local innovative spirit is clearly in evidence in the way these carvers go about their work. Using an electric motor and a belt, the small wooden pieces are spun horizontally at high speed while the workmen use chisels of various shapes to carve out the spindle shape from rectangular wooden blocks.

It takes these workmen barely five to seven minutes to produce a single piece, as the buyers wait eagerly outside.

*

Their little workshop near the railway tracks is close to the Shah Moghul locality of Najibabad, where shops and houses jostle together along narrow winding lanes. Here at the workshop of Faraz Mohammad, who specialises in the production of wooden curtain-rod ends, two workers are using mechanical drills to cut threads into the small wooden pieces while two others screw them on together and pack them into polythene packets.

The raw pieces are carved at one workshop while the polishing is done at another. The raw pieces, packed in empty fertiliser sacks, are left at the workshop by rickshaw pullers who also take them back.

It’s Friday and soon the workers, all of whom are Muslim, will make their way to the afternoon prayer at the mosque. But it is also pay day, and Mohammad is counting out the cash and handing it over to the workers for whom it is a half day.

“I paid out about 1.5 lakh rupees today,” Mohammad tells us after the payments are over. So how did he cope with the BJP government’s note ban declared in November 2016?

Mohammad, a descendant of the Multani brotherhood of carpenters and carvers, shows only sorrow. “We passed through very difficult times… Cash was so scarce. Me and my family waited in queues outside the banks but we could not pay our workers in full. It was not possible for me to borrow the money from elsewhere because no one had any… But I could not let these workers starve, so I paid them whatever I could.”

Mohammad could not afford to lose his workers or his entire business would have fallen apart, with no prospects of revival even in the distant future.

*

Multani craftsmen are present in larger numbers in the neighbouring township of Nagina, a centre of wood carving in the region. Artisans here make wooden boxes of all kinds, some with fretwork or latticework, or designer boxes for storing specialised tools, or specially ordered gift boxes, clothes hangers and many other wooden works that require skilled craftsmanship.

About 80 percent of Nagina’s population is connected with the wood carving business, but after initial hiccups following the cash ban, business has not only recovered but grown. The first person we meet in the wood carvers’ colony is Shahbuddin, who also plays defence part-time in the Nagina football team. Shahbuddin leads us through lanes and bylanes, and past an empty plot to the workshop of Abdul Gaffar for whom he works.

Gaffar, 48, the proprietor of AG Handicrafts, runs a largish workshop here and is the beneficiary of this growth, which has been brought about by rising exports. “Ten percent of wood carvers in Nagina are exporters,” says Gaffar, who has hired about 25 men to work in a 15 by 20 foot courtyard surrounded by rooms – and on its roof as well.

Of course the note ban had an adverse impact on business, as there wasn’t sufficient cash to pay the workers’ weekly wages. But unlike in Najibabad, here the difficult days are now over.

Smartphones and the digital age have come as a boon for his business, says Gaffar whose 17-year-old school going son helps him out in this respect. “We save both money and time due to this and now we have increased our capacity to supply much larger orders than before,” he says with satisfaction.

What about the coming elections? Gaffar has no opinion to offer about the BJP government in his state. The local municipality is more important, he feels. But he does want the government to help set up a wood depot in Nagina, to take it out of the hands of private contractors who charge exorbitant prices. Here he lets slip his endorsement of the Samajwadi Party.

*

Will efforts to create a divide between Hindus and Muslims succeed in this corner of Uttar Pradesh? Not likely, is the general feeling among prominent Hindus as well as Muslims in the area. Some Hindu Vahini posters have appeared in villages near Najibabad, but the closely intertwined network of ties between the two communities means that neither is interested in disturbing the peace.

According to Apoorva Agarwal, a leading young jeweller in Najibabad, the Hindus mostly provide the finance while the skilled craftsmen are Muslims – so the prosperity of one depends on the prosperity of other. Besides, the towns in the area all have populations of about one lakh each, and virtually everyone knows everyone else.

Gaffar agrees with Agarwal’s assessment. He recalls that communal disturbances occurred in Nagina during the Rath Yatra and the Babri Masjid demolition in the 1990s. But that conflict between Hindus and Muslims taught both a lesson which they have not forgotten.

A committee was formed at the time consisting of senior administration officials and prominent members of both communities to ensure that calm was maintained during festivals like Holi, Diwali and Eid. Attempts at provocation have largely failed, including one during Holi in 2018. Similar incidents have taken place in a number of areas in the region but the communities have still maintained peace.

There has never been communal trouble in Najibabad, according to local residents, and relations between Hindus and Muslims are cordial. Though their residential areas are segregated they live virtually next to each other. Take the Rafugaar Mohalla, where India’s last surviving darners live, barely 10 minutes’ walking distance from the railway station. The residences of lower caste Hindus start right where the Muslim neighbourhood ends.

*

What do the people here want? “Better roads and more jobs, and a revival of business activities,” says Israr Ahmed, 65. His words carry weight for he takes the trouble to keep himself informed, making his way each day to the news stand on Najibabad’s main street to buy five newspapers – two in Hindi and three in Urdu.

Ahmed is forthcoming when asked for his opinion of Prime Minister Modi – “He is the most talkative PM we’ve ever had.” He quickly adds that he really admires the prime minister’s energy. He also welcomes the entry of Priyanka Gandhi into Uttar Pradesh politics, likening her to former prime minister Indira Gandhi.

To come to basic infrastructure like power and roads in the area, according to residents inhabitants the power supply has improved vastly over the years. But in Najibabad there are till power cuts of over eight hours a day. In the rural areas it can be presumed that the cuts are longer. The roads are middling though there is an expressway under construction. The concretised parts of it are complete, but some patches are very bad, like the 20 kilometres between Dhampur and Bijnor. “We all end the day covered in dust usually,” says the driver of the taxi that takes us to Bijnor.

*

Back near the Patthargarh Fort there are a number of villages in every direction, one of which is Mahavatpur Billoch. It’s a typical Indian village, but most of the houses and other buildings are now pucca constructions. Nearby are mango groves and the fields are about two kilometres away. Sugarcane and mustard cover the fields which are well irrigated by the Eastern Ganga canal.

Yogendra Pal Singh, 58, an employee of the irrigation department, has just cut a patch of sugarcane from his 6-acre plot since he received a requisition from the local cooperative sugarmill on his mobile phone, and has to supply 60 quintals.

The majority of the residents of Mahavatpur village are from the Scheduled Castes, while Muslims form the second biggest group, and caste Hindus are the minority. According to Singh, the Samajwadi Party is the most influential in the entire area comprising Najibabad. In his village, one would expect a Scheduled Caste head, but actually, the sarpanch is an upper caste landowner. Singh’s son tells us that the upper castes here vote for the BJP.

Notwithstanding their own preference for the BJP they would definitely have liked the government to fix a fair and remunerative price for sugarcane, higher than Rs.325. He has to pay for labour and irrigation. When we meet him he has only one worker in his field – a woman of the name of Vinod Devi who is in her thirties. But many more workers are required at the time of planting – about 40 people per acre – and the minimum wage stands at Rs.300.

*

Taken together, the people of Najipabad, Nagina and Dhampur have not been very happy with the policies of the government, though there is considerable support for the BJP in rural areas. But according to Yogendra Pal Singh the Samajwadi Party is the most influential in the entire region. In combination with the Bahujan Samaj Party it could well mount a strong challenge to the governing BJP.