Why India Does Not Need The CAA-NPR-NRIC

Open Letter by former civil servants

Concerned Citizens, a group of retired civil servants have written an open letter to citizens on the controversy over the Citizenship Amendment Act, the National Register of Indian Citizens and the National Population Register, straightening the facts.They point out that while the government now seeks to delink the three, they considered it their duty as former civil servants to “inform you that the three issues are linked, acquaint you with the facts regarding the NPR, NRIC and the CAA and emphasise why these measures need to be resolutely opposed.”

The letter states:

1. There is no need for the NPR and NRIC

Both the NPR and NRIC exercises flow out of the amendments in 2003 to the Citizenship Act, 1955 (“1955 Act”) and the Citizenship (Registration of Citizens and Issue of National Identity Cards) Rules, 2003 ("2003 Rules") framed by the then NDA government in 2003. The NPR has nothing to do with the Census of India, which is conducted every ten years and is next due in 2021. While the Census collects information about all residents of India without listing their names, the NPR is a list of names of all those who have lived in India for over six months, regardless of their nationality. A Population Register will contain the list of persons usually residing within a specified local area (village/town/ward/demarcated area).

The NRIC will effectively be a subset of the Population Registers for the entire country. The 2003 Rules provide for verification of the details in the Population Register by the Local Registrar (normally a taluka or town functionary) who will separate out cases of doubtful citizenship and conduct further enquiries. After carrying out enquiries in respect of residents whose citizenship status is suspect, the Local Registrar will prepare a draft Local Register of Indian Citizens, which would exclude those not able to establish, through documentary proof, their claim to be citizens of India.

It is at this stage that the experience of the citizens of Assam can cause apprehensions in the minds of those who are required to establish their citizenship, whether or not they profess any religion. The NPR 2020, unlike the NPR 2010, asks not only for the names of the parents of the resident, but also seeks to also record their dates and places of birth. A person who is not able to furnish these details for his/her parents or, for that matter, for himself/herself, could well be classified a “doubtful citizen”.

The 2003 amendments to the 1955 Act (vide Sections 3 (b), 3 (c) and 14A) and the consequent introduction of the 2003 Rules seem to indicate an undue obsession about illegal migrants, without any factual basis. We fail to understand the need for a nationwide identification of “illegal migrants”, which is what the NRIC in effect amounts to, when census statistics over the past seven decades do not show any major demographic shifts, except in certain pockets in some areas of North-Eastern and Eastern India adjoining our neighbouring countries.

We are apprehensive that the vast powers to include or exclude a person from the Local Register of Indian Citizens that is going to be vested in the bureaucracy at a fairly junior level has the scope to be employed in an arbitrary and discriminatory manner, subject to local pressures and to meet specific political objectives, not to mention the unbridled scope for large-scale corruption. Added to this is the provision for objections to the draft Local Register from any person.

The Assam NRC exercise has thrown up the dangers of such a large-scale exercise: lakhs of citizens have been made to spend their life’s savings running from pillar to post to establish their citizenship credentials. Worrying reports are already coming in of people in different parts of India rushing in panic to obtain the necessary birth documents. The problem is magnified in a country where the maintenance of birth records is poor, coupled with highly inefficient birth registration systems. Errors of inclusion and exclusion have been a feature of all large-scale surveys in India, the Below Poverty Line survey and the Socio-Economic Caste Census being prime examples. The recently completed NRC exercise in Assam has been equally error-ridden and has led to major discontent. Indeed the State Government itself, with the BJP in power, has rejected its own NRC data, an extremely ludicrous scenario.

The provisions of the CAA, coupled with rather aggressive statements over the past few years from the highest levels of this government, rightly cause deep unease in India’s Muslim community, which has already faced discrimination and attacks on issues ranging from allegations of love jihad to cattle smuggling and beef consumption. That the Muslim community has had to face the brunt of police action in recent days only in those states where the local police is controlled by the party in power at the centre only adds credence to the widespread feeling that the NPR-NRIC exercise could be used for selective targeting of specific communities and individuals.

Added to the inconvenience that the NPR would put the common person through is the unnecessary expenditure on the NPR exercise, when data which is now to be gathered is already available through the Aadhaar system: these include name, address, date of birth, father/husband’s name and gender. Most Indian citizens are already covered by Aadhaar. The purpose of gathering a lot of the additional data (over and above the Aadhaar details) is unclear and will only give rise to the reasonable apprehension that the bona fide citizen could be enmeshed in an interminable, costly bureaucratic exercise if his/her citizenship status comes under doubt.

Our group of former civil servants, with many years of service in the public sphere, is firmly of the view that both the NPR and the NRIC are unnecessary and wasteful exercises, which will cause hardship to the public at large and will also entail public expenditure that is better spent on schemes benefiting the poor and disadvantaged sections of society. They also constitute an invasion of the citizens’ right to privacy, since a lot of information, including Aadhaar, mobile numbers and voter IDs will be listed in a document, with scope for misuse.

2. Why authorise widespread setting up of Foreigners’ Tribunals and detention camps?:

The Foreigners (Tribunals) Amendment Order, 2019 (issued on 30 May 2019) has unnecessarily stoked fears that Foreigners’ Tribunals can now be set up on the orders of any District Magistrate in India and is the precursor to a widespread exercise to identify “illegal migrants”. While the central government may contend that there is no such intention, it was surely impolitic, given the prevailing atmosphere in Assam and elsewhere, to issue such blanket orders delegating powers for constituting Foreigners’ Tribunals.

The experience with Foreigners’ Tribunals in Assam has been, to put it bluntly, traumatic for those at the receiving end. After running the gamut of gathering documents and answering objections to their citizenship claims, “doubtful citizens” have also had to contend with these Tribunals, the composition and functioning of which were highly discretionary and arbitrary. Consequently, a number of citizens lost their lives in the quest for affirming citizenship or have had to suffer the indignity of incarceration in detention camps.

There have also been media reports, not denied by the Government of India, that orders for setting up detention camps have been given to all state governments. We are frankly bemused by the Prime Minister’s recent statement that no such camps are in existence, when reports have documented the construction of such camps in states as far apart as Goalpara in Assam and Nelamangala in Karnataka and the intention to construct a detention centre in Navi Mumbai in Maharashtra.

The Government of India has not come out with any statistics to show that the “illegal migrants” problem in India is so severe that it requires the large-scale construction of detention camps all over the country.

3. The constitutional and moral untenability of the CAA:

We have our grave reservations about the constitutional validity of the CAA provisions, which we also consider to be morally indefensible. We would like to emphasise that a statute that consciously excludes the Muslim religion from its purview is bound to give rise to apprehensions in what is a very large segment of India’s population. A formulation that focused on those suffering persecution (religious, political, social) in any country in the world would not only have calmed local apprehensions but would also have been appreciated by the international community.

In its current formulation, the CAA does not even mention the word "persecuted", probably because using this word in the context of Afghanistan and Bangladesh would have marred India's relations with these countries. Given that the Government of India has powers to grant citizenship after a migrant has completed eleven years in India, it would be instructive to know whether the Government of India has cleared all pending cases of “illegal migrants” till end-2008.

Since the discretion to grant citizenship and to exempt individuals/groups from the purview of the Passport Act, 1920 and the Foreigners Act, 1946 lies entirely with the Government of India, this discretion could have been exercised on a case by case basis by the Government of India without any need to go through the exercise of the CAA and mentioning specific communities from specific countries.

What has given rise to grave apprehensions about the intentions of the Government of India has been the rash of statements by Ministers of the Government of India in recent times, linking the NRIC and the CAA. The Prime Minister’s statement at a public meeting in Delhi on 22 December that the CAA and the NRIC are not linked contradicts the averments of his Home Minister on repeated occasions in various fora.

In such a welter of conflicting and confusing utterances, it is hardly surprising that the ordinary citizen is left bewildered and is overcome by unknown fears, more so when government has not entered into any dialogue on this issue. At a time when the economic situation in the country warrants the closest attention of the government, India can ill afford a situation where the citizenry and the government enter into confrontation on the roads. Nor is it desirable to have a situation where the majority of State Governments are not inclined to implement the NPR/NRIC, leading to an impasse in centre-state relations, so crucial in a federal set up like India. Above all, we see a situation developing where India is in danger of losing international goodwill and alienating its immediate neighbours, with adverse consequences for the security set-up in the sub-continent. India also stands to lose its position as a moral beacon guiding many other countries on the path to liberal democracy.

We, therefore, urge our fellow citizens to insist, as we do, that the Government of India pay heed to the voice of the citizens of India and take the following steps at the earliest:

Repeal Sections 14A and 18 (2) (ia) of the Citizenship Act, 1955, pertaining to the issue of national identity cards and its procedures and the Citizenship (Registration of Citizens and Issue of National Identity Cards) Rules, 2003 in its entirety.

Withdraw the Foreigners (Tribunals) Amendment Order, 2019 and withdraw all instructions for construction of detention camps.

Repeal the Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019.

Signed: CONSTITUTIONAL CONDUCT GROUP

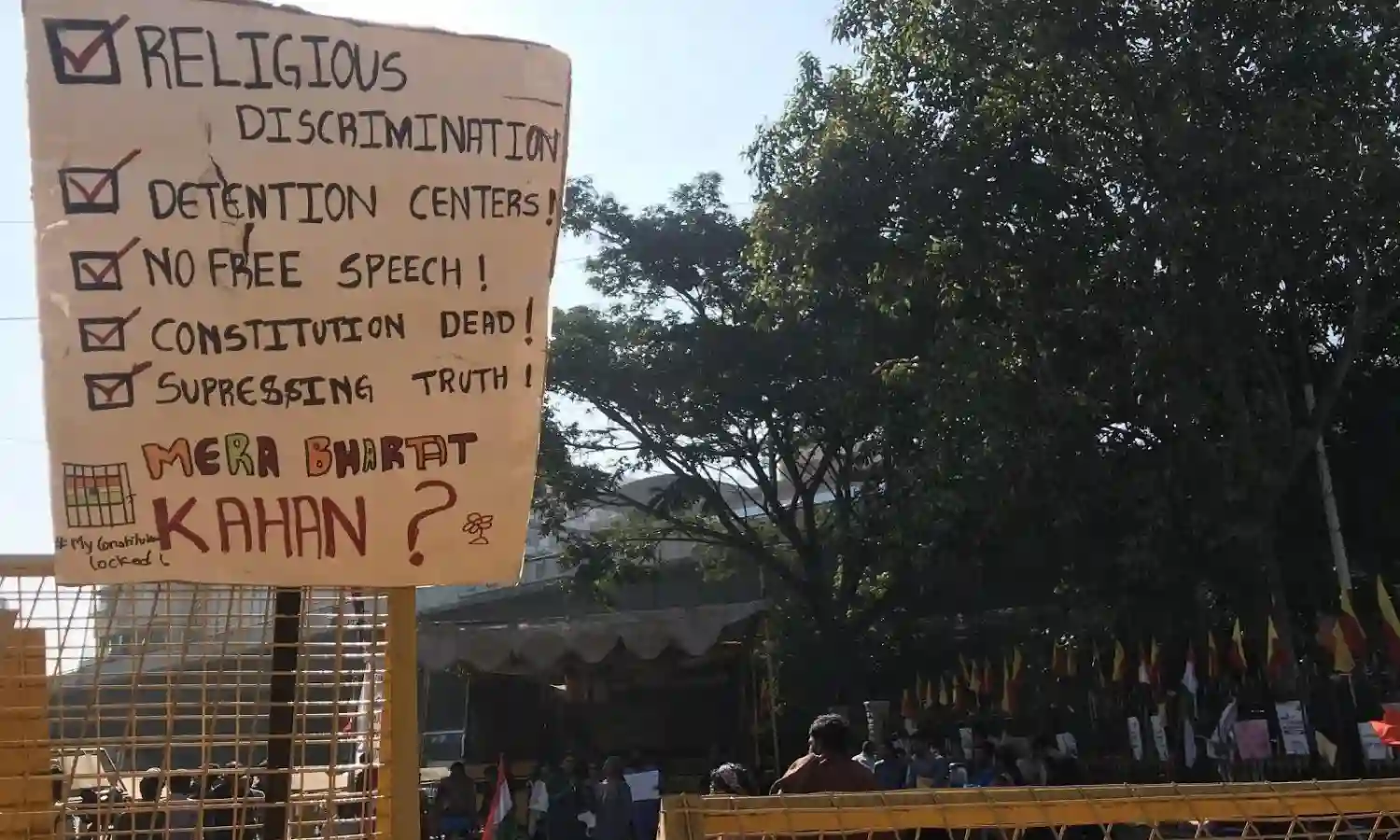

Cover Photograph: 24 hour protests in Bengaluru