Writing on the Wall

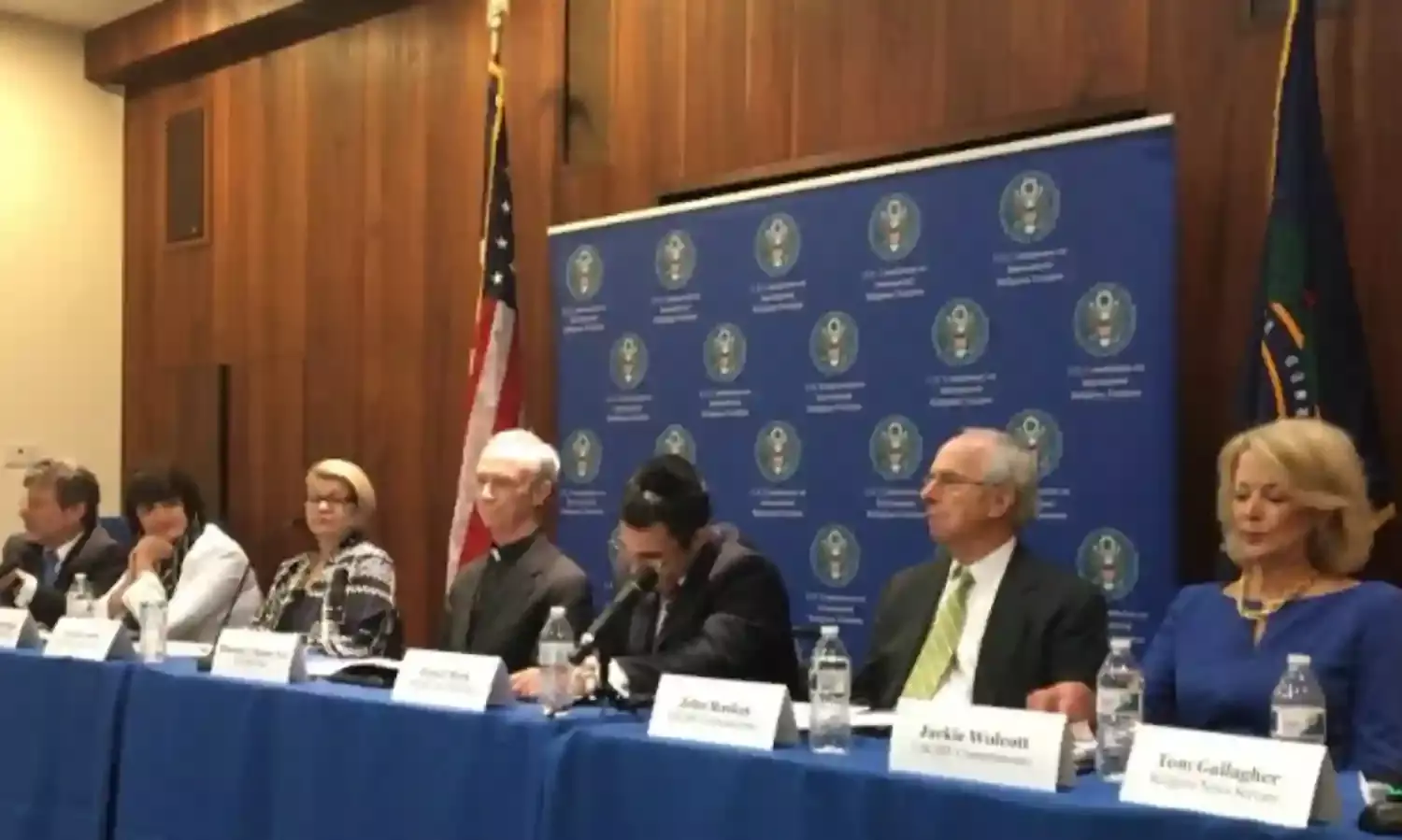

USCIRF report

Factually speaking, one must be a cynic to be dismissive about the findings of the annual 2022 report on India in the US Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF).

In particular, the report recommends that India be designated as a Country of Particular Concern, a country that engages in “particularly severe” violations of religious freedoms and on which sanctions be imposed on individuals and entities responsible by freezing their assets and barring their entry into the US.

It calls on the USG to promote human rights of all religious minorities in India; raise this issue through bilateral & multilateral forums “such as the ministerial of the Quadrilateral,” and take it up in the bilateral relationship as well as highlight the US’ concerns through Congress. [Emphasis added.]

The report is direct, explicit and forceful in targeting the Modi Government and the BJP — “The BJP-led government, leaders at the national, state and local levels, and increasingly emboldened Hindu-nationalist groups have advocated, instituted and enforced sectarian policies seeking to establish India as an overtly Hindu state, contrary to India’s secular foundation and at grave danger to India’s religious minorities.” It leaves no scope for misinterpretations.

To rub salt into the wound, while releasing the document in Washington on June 2, Secretary of State Antony Blinken made an acerbic remark that “For example, in India, the world’s largest democracy and home to a great diversity of faiths, we’ve seen rising attacks on people and places of worship.”

To be sure, the government is touched to the quick, although there’s no wriggle room here. The MEA spokesman evasively responded that “vote bank politics is being practiced in international relations” and cited “issues of concern” in America too, “including racially and ethnically motivated attacks, hate crimes and gun violence.”

The government has chosen to resort to polemics to downplay the report, hoping this awkward moment will pass. That may well turn out to be the case. India picks its fights selectively, and the US is not the OIC. Per past practice, the endeavour will be to “constructively engage” the Biden Administration on other productive fronts (eg., defence ties) that would restrain the latter from going on a path to lock horns over religious freedom in India.

Crucially, will the USCIRF’s condemnation make any difference to the Hindutva agenda as such? That seems highly unlikely, while the intensity of its practices in national life may vary from time to time.

On closer look, however, it transpires that in comparison with all other countries that have been mentioned as “countries of particular concern” by the USCIRF, it is only India where conditions are deemed to have “significantly worsened” during 2021 — curiously, alongside Taliban-run Afghanistan and the military dictatorship in Myanmar.

In comparison, the USCIRF estimates that conditions continued their negative trajectory” in Pakistan and “remained poor” in Iran; while, in Saudi Arabia, they actually showed “some incremental improvements,” and in Eritrea, they “improved slightly but overall they remain poor.”

The point is, India’s democratic backsliding is as much on the US radar today as the human rights issues. Furthermore, in what can be called other “technocratic issues” — such as the UN forums, G-20, data localisation rules, cyber issues, climate change, and so on — Indian stance happens to be more in harmony with China’s or Russia’s than with the US.

Succinctly put, India is paying a price for its pretensions to have a “value-based relationship” with the US and to be sharing a commonality of interests with regard to the “rules-based order.” You can’t have the cake and eat it, too!

The US has every right to hold the bar high for India in comparison with, say, Pakistan and Saudi Arabia or Russia and China. And on its part, India ought to have every obligation to clear that bar of democracy. At least, India must make a genuine effort.

Conversely, if the effort is too taxing or is simply unacceptable for reasons of political expediency domestically, India must cease to pretend what it is not, or cannot and will not be. Fundamentally, the contradiction here is that India is setting impossible standards for itself and creating unrealistic expectations in the western, liberal order.

There were enough warning signals recently. In the run-up to the virtual Summit for Democracy last September, the influential American opinion maker and watchdog Freedom House had issued a scorecard of the participating countries, where India was singled out as a country where the political rights of Indian Muslims were “threatened” and “marginalised segments of population faced obstacles to full political representation”; human rights and advocacy groups “faced threats, legal harassment, excessive police force, and occasionally lethal violence.”

Freedom House noted that the Indian government continued to “harass journalists” and “impose frequent internet shutdowns”. However, when the US government-funded, non-profit Freedom House downgraded India’s status from a “free” to a “partly free” country, there was an immediate outcry from the external affairs ministry, information and broadcasting ministry and even the Union finance minister, dismissing the assessment as “inaccurate.”

On the other hand, Prime Minister Narendra Modi in his intervention at the virtual Summit for Democracy went on to underline the “need for democratic countries to deliver on values enshrined in their constitutions,” and also claimed that the “four pillars” of India’s democratic government are “sensitivity, accountability, participation and reform orientation”. Are we matching these high standards in our actual performance? If not, the USCIRF report needs to be seen as a writing on the wall rather than be rejected and ridiculed as an act of American double standards.

Ambassador M.K.Bhadrakumar is retired from the Indian Foreign Service.