Unrestrained 'Privatisation of Poverty-Reduction' Puts Human Rights at Risk

Corporate lobbyists are unusual guests at development meetings, but when the United Nations held its Financing for Development conference in Addis Ababa this week to decide who pays for its new “Sustainable Development Goals”, some governments laid out the red carpet for the private sector.

Unfortunately, the conference failed to agree on any mechanism for making sure the role of companies in development is kept transparent and accountable.

Some see giving companies a bigger role in development as a simple win-win. Governments get access to financing to take the pressure off aid budgets and come up with the 2.5 trillion dollars needed to respond to poverty and climate change, while meeting the housing, health, education and infrastructure targets in the post-2015 agenda.

On the other hand, companies get a potential say in policy making and access to juicy public contracts.

But before governments allow companies to shoulder significant responsibility for fighting poverty, climate change and other global challenges, they will have to convince critics who warn that they are putting the fox in charge of the henhouse.

While getting companies involved in development has the potential to provide important sources of funding to improve lives, experience equally shows that when companies are not held to account, people and communities can be seriously harmed.

If private sector involvement in development is going to pay off for the people who need it and not just corporate shareholders, states have to leave impunity at the door.

Increasing the role of the private sector in the delivery of crucial public services such as water, education and health is fraught with risk. On July 2, the U.N. Human Rights Council warned that without proper regulation the privatisation of education could put the right to education at risk for countless children, especially if it means those children who cannot afford to pay lose out on quality education.

Around the world, Amnesty International has documented too many cases of marginalised communities waiting to see justice done, sometimes for decades, for human rights abuses perpetrated after a multinational company rolled into town. States who seek the involvement of the private sector in advancing development goals without putting effective safeguards in place, forget these cases at their peril.

The more than 570,000 victims of the 1984 Bhopal toxic gas leak, India’s worst industrial disaster, are still waiting for justice more than 30 years later. The firm responsible, Union Carbide, is now owned by U.S.-based Dow Chemical. A Bhopal court is pursuing criminal charges against Dow but the company has failed to even show up to multiple hearings over the last year. Meanwhile, survivors have tried and failed to seek justice in both India and the U.S.

While Union Carbide paid some compensation to those affected under a 1989 settlement agreement with the Indian government, it was wholly inadequate to cover the harm caused and there were serious issues with the way it was paid out to victims. At the time, the Indian government lacked the leverage to effectively hold a powerful global company to account.

Foreign companies operating in countries that are rich in natural resources and poor in regulation can reap huge profits at the expense of vulnerable people.

Earlier this year Amnesty International warned that Canadian and Chinese mining giants have profited from, and in some cases colluded, with human rights abuses by the Myanmar authorities to exploit one of the country’s most important copper mines, with thousands of people being illegally driven off their lands, serious environmental risks going unchecked, and peaceful protest brutally suppressed.

Far from investigating the abuses, one multinational company involved used an opaque trust fund in the British Virgin Islands to divest its investment, in a manner which possibly breached economic sanctions applicable at the time. Reducing their exposure to the problem, rather than fixing it, has often been the mantra of companies faced by scandalous abuses.

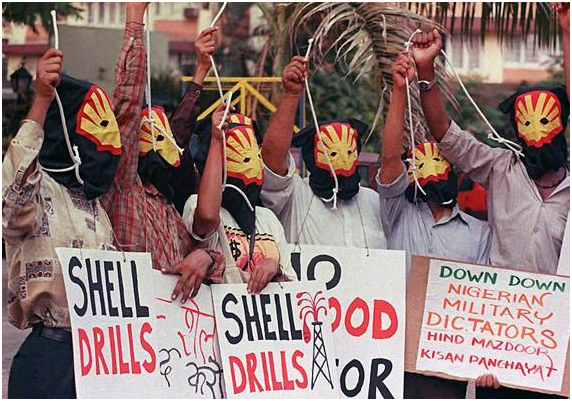

For residents of Niger Delta, the legacy of half a century of oil production in Nigeria is the devastation of their farming and fishing lands. Today the oil spills continue unabated. In Shell’s operations alone, there were 204 spills in 2014. Shell blames sabotage and theft, but old pipelines and badly maintained infrastructure are a major cause of pollution.

This year one local community in Bodo has finally won 80 million dollars in compensation from Shell for the impacts of a massive spill, but only after a lengthy court battle in the UK and years of false claims by the company.

These are cautionary tales world leaders should consider as they plan to entrust the private sector with responsibility for funding and carrying out development projects. In all these cases, corporate political and financial clout created barriers to local communities accessing justice and accountability.

Governments have watched corporate political power grow for decades, often doing their best to get out of its way instead of properly regulating it to ensure that human rights are not violated.

Corporate lobbyists, meanwhile, have done everything possible to ensure that the important international standards addressing these risks remain entirely voluntary. Voluntary codes of conduct and standards that have no enforcement mechanism ultimately lack the teeth to really change corporate behaviour, and when abuses occur, they can leave victims with little or no hope of remedy.

If private sector involvement in development is going to pay off for the people who need it and not just corporate shareholders, states have to leave impunity at the door. Companies that want to make a profit through work on sustainable development must be required to show they have a clean track record when it comes to human rights.

They must demonstrate that they have internal systems that ensure they do not cause human rights abuses. They must disclose information to communities about any local operations that impact them, as well as any payments they make to the authorities.

Crucially, governments must be ready to hold companies to account when abuses happen. The failure of all but five countries to meet the U.N.’s official aid targets is a crying shame, but if filling the gap by giving the private sector free rein leads to human rights abuses in already vulnerable communities, it will only rub salt in the wounds that sustainable development is supposed to heal.