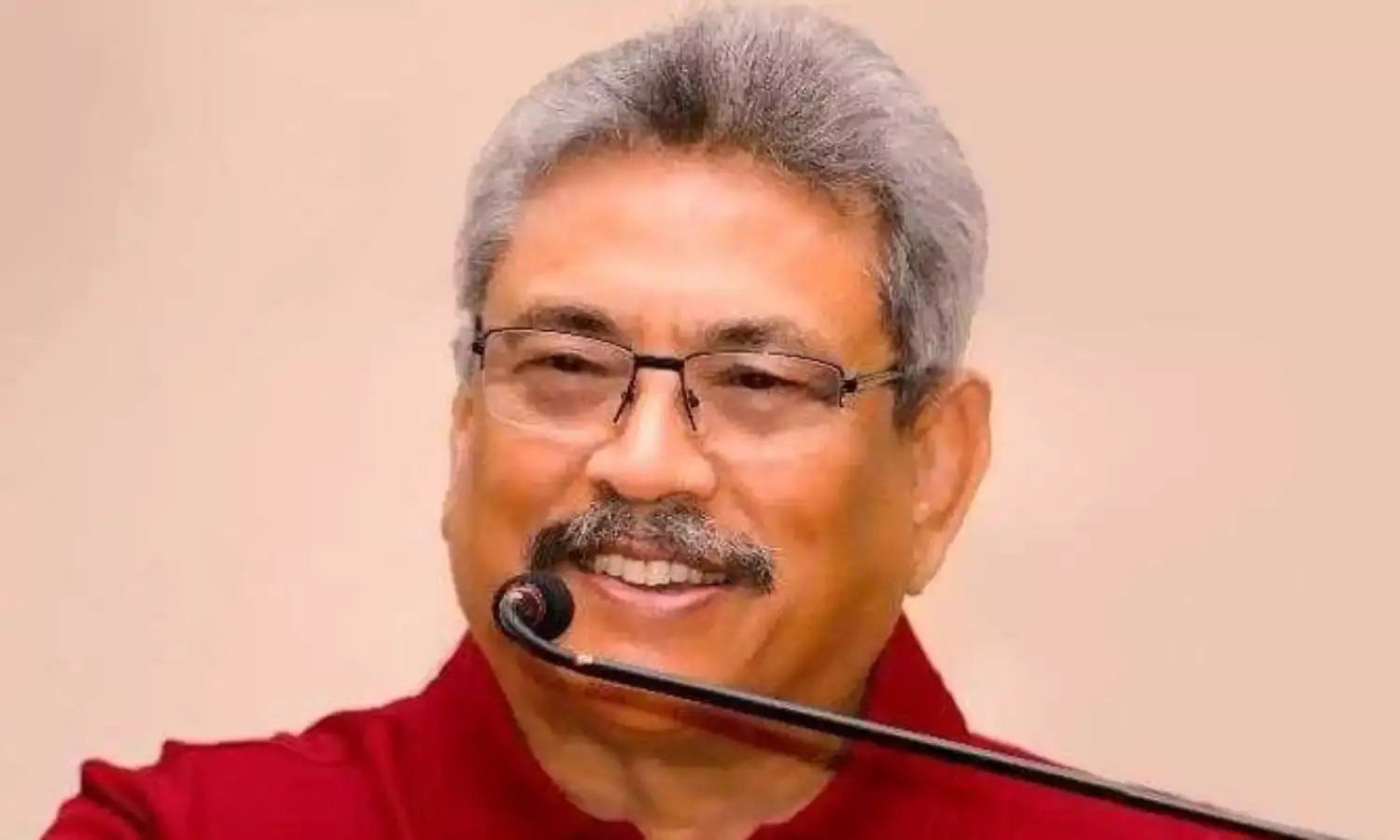

Misconceptions about Gotabaya’s Legal Immunity in Lanka and US

Still not out of the woods in the US where he has two cases against the new PM

COLOMBO: There is trenchant criticism in a section of the Sri Lankan and foreign media that the newly-elected Sri Lankan President Gotabaya Rajapaksa has used his powerful position to engineer his release from prosecution in Sri Lanka.

It is also said that he is still not out of the woods in the US where he has two cases against him: First, an appeal against a lower court’s dismissal of a case in which Ahimsa Wickramatunge had alleged that he had ordered the killing of her father, Sunday Leader editor Lasantha Wickramatunge; and Second, a case in which he had allegedly ordered the torture of one Samathanam, a young Sri Lankan Tamil who had sought refuge in Canada.

But these assertions are based on ignorance of the Lankan constitution and legal conventions in the United States.

Sure enough, within days of his assuming office Gotabaya was released from all indictments filed over the alleged misappropriation of public funds for the construction of the D A Rajapaksa Memorial. The Permanent High Court’s Trial at Bar also lifted the overseas travel ban imposed on Rajapaksa and released his impounded passport.

The release from this case followed a submission by the Attorney General’s representative, that as per the constitution of Sri Lanka, no civil or criminal proceedings could be conducted against a serving President. Constitutionally, Gotabaya’s release was automatic, though he can be prosecuted when he becomes a private citizen.

In the US, a foreign Head of State or Head of Government enjoys immunity for acts committed in his country in his official capacity. And, interestingly, as in the case of the former Chinese President, Jiang Zemin, Gotabaya would enjoy immunity even after he ceases to be Lankan President.

In the case filed by Ahimsa Wickrematunge, the US District Court of Central District, California, decided to grant Gotabaya immunity on the grounds that he was entitled to “common law foreign official immunity for the acts that were alleged.”

Ahimsa has since appealed to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeal. In the appeal, her plea was that the murder was not an act committed in Gotabaya’s official capacity because it was not authorized or ratified by the Sri Lankan government.

Be that as it may, now that Gotabaya is President of Sri Lanka, he would automatically get immunity against prosecution in the US.

The cases filed against Zimbabwe President Robert Mugabe and the Chinese President Jiang Zemin were not entertained because they were foreign officials who enjoyed immunity against prosecution in the US for acts done in their in their country and in their official capacity.

The US government usually submits to the concerned courts that the cases against such foreign officials should be dropped for “diplomatic reasons and in the national interest.” And the courts do drop the cases.

In an article on “Extraterritorial Application of American Criminal Law” in https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/94-166.html#_Toc465870142 it is pointed that though the US constitution grants Congress broad powers to enact laws of extraterritorial scope and imposes few limitations on the exercise of that power, prosecutions are relatively few, because of the practical, legal, and diplomatic obstacles that appear on the way.

Manmohan Singh and Sonia Gandhi

The Sikhs for Justice (SFJ), a New York-based organization, had filed a civil case in the District Court of District of Columbia, against Dr. Manmohan Singh when he was visiting the US as the Prime Minister of India. The charge was that he, as Indian Finance Minister in the 1990s, was responsible for funding anti-insurgency operations in Punjab which had resulted in “over 100,000 Sikhs being killed.” The case against Dr Singh was filed under the Alien Tort Claims Act and Torture Victim Protection Act.

The 24-page complaint also said that during Singh's tenure as Prime Minister since 2004, he had “actively shielded and protected members of his political party who were involved in organizing and carrying out genocidal attacks on the Sikhs in November 1984 resulting in the death of more than 30,000 Sikhs.”

The plaintiffs sought compensatory and punitive damages.

Earlier, the SFJ had filed a case in New York against Congress President Sonia Gandhi. The SFJ served the summons at the Memorial Sloan Kettering, where Gandhi was undergoing treatment. But the employees of the hospital did not touch it, and the police had taken it away.

At any rate, the courts did not proceed on the Manmohan Singh and Sonia Gandhi cases “in America’s national and diplomatic interest.”

Mugabe and Jing Zemin Cases

Sarah Andrews, a policy analyst at the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in Paris, has written a detailed account of US law in practice in the Robert Mugabe and Jiang Zemin cases.

Here are excerpts from her account: On October 6, 2004 the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit ruled that Robert Mugabe, President of Zimbabwe, enjoyed absolute inviolability and immunity from U.S. jurisdiction.

A similar decision has been issued a month earlier by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit in respect of a case against Jiang Zemin, former President of the People's Republic of China.

Both cases were civil lawsuits alleging serious human rights abuses in violation of the Alien Tort Claims Act, the Torture Victim Protection Act, and international human rights norms.

Mugabe Case

The case against President Mugabe began in September 2000 when, during his visit to the United Nations Millennium Summit, a complaint was filed against him by citizens of Zimbabwe in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York.

The plaintiff had accused him of engaging in extrajudicial killing, torture, terrorism, rape, beatings and other acts of violence and destruction. The complaint also named as defendants Foreign Minister Robert Mudenge and the ruling political party, the Zimbabwe African National Unions-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF).

In February 2001, the U.S. government intervened in the case, filing a "suggestion of immunity" on behalf of President Mugabe and Foreign Minister Mudenge. The government asserted that Mugabe and Mudenge were entitled to absolute immunity from jurisdiction under the customary international law doctrine of head of state immunity.

In addition, it claimed that, as representatives of the Government of Zimbabwe to the United Nations Millennium Summit, both Mugabe and Mudenge were entitled to diplomatic immunity under the Convention on Privileges and Immunities of the United Nations ("the U.N. Convention") and the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations ("the Vienna Convention"). Even Mugabe’ political party was asked to be let off the hook. The court concurred and obliged the government.

Jiang Zemin case

The case against Jiang Zemin, then-President of the People's Republic of China was filed in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois ("the district court") in October 2002 during an official visit by Zemin to the U.S.

The complaint alleged torture, genocide, and other major human rights abuses perpetrated against practitioners of the Falun Gong spiritual movement.

As in Mugabe, the complaint named as an additional defendant a non-governmental third party, the Falun Gong Control Office ("Office 6/10").

Subsequently, Zemin departed from the office of President. As the protection afforded a former Head of State is substantially less than that afforded an incumbent head of state, the Plaintiffs argued that as a now-former Head of State, Zemin was no longer immune from the jurisdiction of U.S. courts.

But intervening in the case, the U.S. government argued that as a recognized head of a foreign state at the time the case was filed, Zemin was entitled to absolute immunity from jurisdiction and inviolability from all service of process, both on his own behalf and on behalf of the Falun Gong Control Office.

The district court accepted the government's assertion of immunity on behalf of Zemin as conclusive and binding upon it.

On appeal by the plaintiffs, the Seventh Circuit upheld the lower court's dismissal of the complaints against Zemin.

International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (I.C.J) addressed the question of immunity in the Congo v Belgium case. There it held that under customary international law, a Foreign Minister (and by extension a Head of State) enjoys absolute immunity from "any act of authority of another State" regardless of the gravity of the charges involved, for as long as he or she remains in office.

Pinochet Case

However, Sarah Andrews says that after the landmark decision of the UK House of Lords in the Pinochet case, it is now increasingly accepted that former Heads of State do not enjoy a lasting immunity for acts taken in violation of international criminal law, even when committed under the guise of official authority.

Diplomatic Interest

Be that as it may, the most important and over-riding factor in such high profile cases are not so much points of law but exigencies of international relations, diplomacy and the “national interest.” Courts go by the advice of the government in these cases.