The West Pieces Together What Life Will Be Like Under the Taliban

Intense speculation

With the US withdrawing all its troops from Afghanistan by August 31, and the radical Islamist Taliban likely to seize power from the pro-Western, ideologically middle-of the-road government in Kabul, there is intense speculation on what Afghanistan will be like under Taliban.

AFP quotes Taliban officials saying that 85% of Afghanistan is already under the oufit. And according to a top US military commander, the Taliban could be controlling the whole country within the next six months. No wonder a lot of attention is being given to the likely scenario in the event of a Taliban take-over.

The popular Western expectation is that the Taliban will impose a rigidly Islamic order preventing progress towards modernity, tolerance and democracy. Afghanistan will be on a self-destructive path, it is said. But research done by Westerners themselves yields a less gloomy picture. The latter point out that the Taliban has been moving towards modernity, albeit cautiously, selectively and tentatively, while being rooted in Islamic values.

For the Taliban, this is perhaps the best way to go about it. Past experience shows that attempts to radically change societies deeply rooted in tradition (whether Islamic or otherwise) will fail. They could, in addition, trigger a counter revolution. Afghanistan itself saw such a reaction when a Soviet-backed communist regime in Kabul attempted radical changes. It is the Soviet-engineered change which created the Taliban.

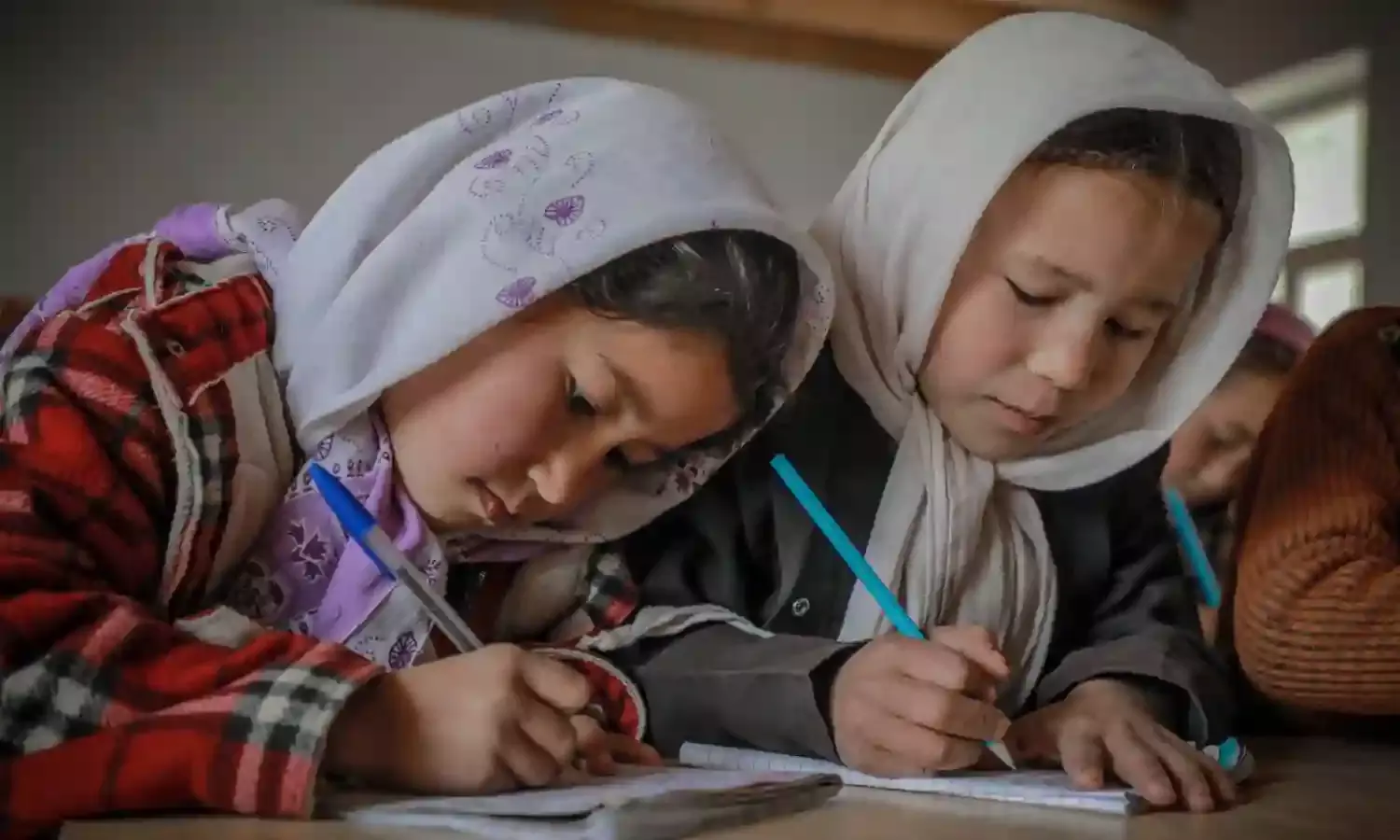

The gloomy scenario of an Afghanistan under the Taliban was presented in a report by Human Rights Watch (HRW) in 2020. The report was based on interviews with people who had lived in Taliban-ruled areas. It said that although the Taliban officially stated that they no longer opposed girls’ education, very few Taliban officials actually permitted girls to attend school after puberty.

The report quotes a school teacher in Wardak province in central Afghanistan as saying: “Today, a Taliban official tells you that they allow girls up to sixth grade, but tomorrow, when someone else comes instead, he might not like girls’ education.”

Moral policing with harsh punishments were the order of the day. “Vice and virtue” police stalked the Taliban-occupied districts, as they did when they ruled the whole of Afghanistan in the 1990s. The police watched out for and punished people who transgressed social and dress codes. According to a recent AFP story, singers and artists are now apprehending a ban on their activities as was the case in the 1990s. Under the Taliban, women who were victims of domestic violence, were asked by the Taliban-run courts to pursue familial mediation instead of a legal remedy.

However, Ashley Jackson and Rahamatullah Amiri in their paper entitled: Insurgent Bureaucracy: How the Taliban Makes Policy (published by the United States Institute of Peace in November 2019) say that the Taliban is not a monolith but a patch work.

“Multiple actors—from the Taliban leadership to local commanders—have played a key role in creating and shaping the movement’s policy in Afghanistan. Taliban policymaking has been top-down as much as it has been bottom-up, with the leadership shaping the rules as much as fighters and commanders on the ground. The result is a patchwork of practices which the leaderships adopt to exert control.”

“While the rules might have been set at the top level, local variance, negotiation, and adaptation were considerable. Policymaking has been driven by military and political necessity as the Taliban needed to control the civilian population and compel its support. Beyond this, a mix of ideology and local preferences has guided policymaking and implementation,” the authors said.

Jackson and Amiri also point out that as the Taliban became more and more powerful and world powers began to cultivate them, they found value in securing international legitimacy. But adding a note of caution, they say that although international recognition had become a priority for the top leadership, commanders on the ground were often driven by immediate military concerns, ideology, and local preferences. Thus, Taliban’s policies tended to be uneven and chaotic.

In 2018, the Danish Overseas Development Institute at Kabul, had interviewed more than 160 Taliban fighters, officials and civilians to find out how the Taliban governed civilians. This study also found that over the years, Taliban’s governance had become more coherent and rational. High-level commissions began to govern sectors such as finance, health, education, justice and taxation with clear chains of command.

There was better coordination with government departments and international aid agencies to provide public goods and services, though the Taliban insisted on exercising overall control over them. State education was initially banned, but later, when the Taliban came under civilian pressure to open schools (other than Madrassahs), they opened schools. But education continued to be “heavily regulated” by Islamists.

NGO and government-provided services operated in the Taliban-held areas but strictly as per Taliban’s rules. Service delivery ministries and NGOs struck deals and signed MoUs with the local Taliban. The Taliban regulated State utilities departments, collecting bills of the state electricity company in at least eight of Afghanistan’s 34 provinces and controlling around a quarter of the country’s mobile phone coverage. The Taliban’s taxes coopted Islamic finance concepts, such as oshr and zakat, while at the same time, following secular official systems.

The Taliban monitored health workers and prevented payment to those who shirked work. They inspected equipment and medical stocks in clinics. Instead of driving out NGOs and government service providers, as they did previously, they encouraged them to expand.

In August 2007, Taliban leaders gave the World Health Organization (WHO), the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and their implementing partners permission to conduct polio vaccination. A letter instructed fighters to allow vaccinations and urged parents to have their children vaccinated.

By 2011, the Taliban leadership had signed agreements with at least 26 aid organizations and enunciated a clear central policy for negotiating with NGOs.

The Danish study noted that the Taliban had sought to correct many of the flaws and shortcomings that undermined their rule in the 1990s which led to their ouster from power by US-led opposition forces in 2001.

Apart from lifting the ban on women and girls attending school, and allowing inoculation, the Taliban began to respect non-Pashtun ethnic groups. Rapprochement with the ethnic minorities is a major step forward because the Pashtun-dominated Taliban had been at odds with other tribes like the Turkman and the Uzbeks.

Uzbeks were part of the Northern Alliance, which fought against the Taliban regime. After the fall of the Taliban in 2001, the Uzbeks had gained influence in the military and political life of Afghanistan. But discontent with successive central governments in Kabul coupled with a feeling that they could not provide adequate protection, drove at least some members of minority communities to the Taliban, says the Minority Rights Group.

Recently, the Taliban started recruiting heavily from ethnic minorities, expanding their territories in the minority-dominated north. Qari Salahuddin Ayubi, an ethnic Uzbek, was the Taliban’s ‘shadow Governor’ in Faryab, He was killed by a NATO airstrike in 2015.

In conclusion the Danish study says: “The Taliban’s circumstances have radically changed since 2001. Their objectives and policies have shifted accordingly. They are no longer a revolutionary movement as they were in the 1990s, but a deposed government and the main armed opposition faction fighting a pro-Western government supported by foreign troops.”

“As an insurgency, the movement has had to reconcile its traditionalist ideology with both the demands of securing the population and exposure to a much broader field of ideas and influences.”

Cover Photograph: Schoolgirls study in a school in the contested district of Argo in the Badakhshan province in northern Afghanistan. Courtesy of the Norwegian Afghanistan Committee/Photographer: Sediq Hazrati. (The Fuller Project)