Gulf Beyond Oil And US

DUBAI: The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries’ emphasis on a non-oil economy during the last 15 years reached a crescendo this week. Unveiling the ‘Vision 2030’ plan, Saudi Arabia said: “We can live without oil in 2020.” This deadline may not be sacrosanct, but driven by the ‘spirit of possibility’, the region is certainly more realistic than ever before about operationalizing ‘life beyond oil’ sooner than later.

In this economic milieu, it is worth exploring another regional dynamic – ‘life beyond the United States’.

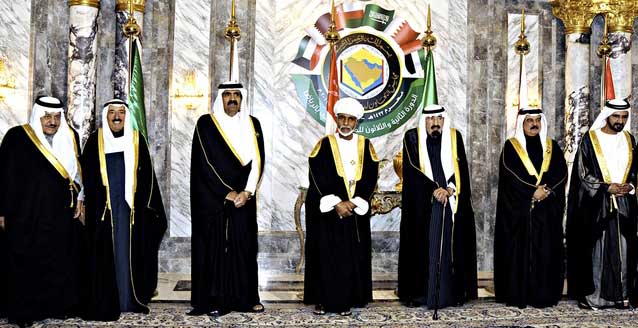

No matter what the GCC and the United States say in the current context, the closest they can get metaphorically and literally is around a summit table, like they did in Riyadh last week. While each of the GCC countries and Washington will continue to have varied degrees of engagement, GCC-US collective ties are unlikely to match its robust past.

Formerly, US ‘public’ policy mostly influenced the ‘private’ views of the President. During the last seven years of Barack Obama’s reign, however, his private views have conditioned US public policies, both domestic and foreign.

The approach towards Iran, Cuba, Syria, Iraq, Guantanamo Bay, and the ‘pivot to Asia’ are some dramatic changes in Obama’s foreign policy. It seems unlikely that any future US president – Republican or Democrat – would be able to alter them significantly, let alone reverse them.

In the context of GCC-US ties – after being the security guarantor of the six countries against perceived Iranian threat – the United States has turned the tables by striking a deal with the Islamic Republic. How much ever Washington emphasizes on shoring up GCC’s security and reining in Iran, US-Iran ties are also unlikely to match their adversarial past.

No matter what the compulsions of the GCC-Iran friction are, Washington-Tehran ties have their own dynamics, dictated by their domestic interests, including their current leaders’ character, and would continue to be driven by them rather than the GCC bloc’s concerns – however genuine they are.

Over the last few weeks, the media has publicized Obama’s comments in the Atlantic magazine – particularly about GCC countries being “free riders” and the need for them to “share” the Middle East with Iran. What received less publicity is another candid comment: “There’s a playbook in Washington that presidents are supposed to follow. It is a playbook that comes out of the foreign policy establishment. And the playbook prescribes responses to different events, and these responses tend to be militarized responses. Where America is directly threatened, the playbook works. But the playbook can also be a trap that can lead to bad decisions.”

Learning from the misadventures of the George W. Bush administration, the gist of Obama’s foreign and defence policy pronouncement in the 2014 State of the Union address was that Washington would limit US military intervention in conflicts around the world. Linking this to Washington’s policies in Syria and Iran reflects either or both the following sentiments: the United States’ decline as an unchallenged superpower due to its economic woes of the last decade; and, and as a consequence perhaps, the desire to focus on domestic issues at the expense of its international role.

Slowly – even reluctantly – but surely, even the American public opinion is seeing logic in Washington minding its own business.

So, what next for the GCC countries? Following are plans B and C – not necessarily in their order of importance.

Plan B – Like the GCC countries have been preparing for ‘life beyond oil’ through economic diversification, they also need to intensify their security diversification policies. During the last decade and a half, the GCC countries have been talking against putting all eggs in one basket – “omnibalancing” or multiple partners and alliances to address national security issues. Such a new ‘collective’ security architecture in the future would not exclude the United States, but include other actors, particularly from Asia, thus aligning the economic-security interests in these changing times.

Plan C – While Iran ‘meddles’ in the Middle East, it is time to create a binary in its interference. The GCC countries should try to ‘sub-regionalize’ Iran’s disturbances by paying more attention to what it is doing and what it should not do in the GCC countries than in the rest of the wider region. Iran may be more inclined to restrict its support and influence in the GCC countries than give up ‘all’ interference. This could both improve GCC-Iran ties (even if it is US propagated “cold peace”) and promote Gulf security and stability.

Ideally, the GCC countries need to talk to Iran directly to bridge the gulf. If this is difficult, intermediaries could be used – either Asian or American or even a ‘P5 Plus’ kind of collective approach.

A ‘combo’ of the above plans may, perhaps, eventually be a win-win development for all.

(The author is a Dubai-based political analyst, author and Honorary Fellow of the University of Exeter, UK.)