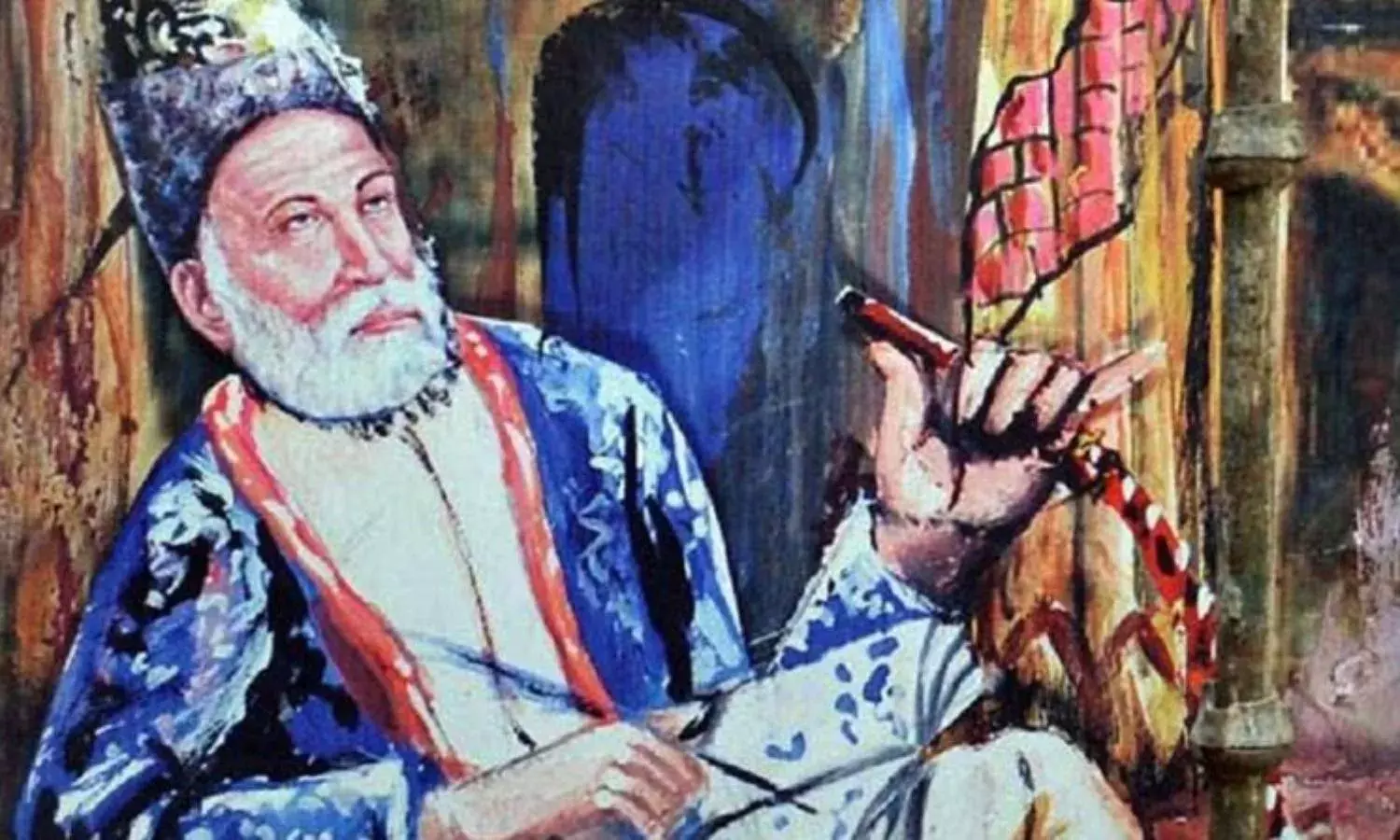

GHALIB

An essay on Ghalib by the late Umakanta Mahapatra.

Ghalib remains a wonder and a puzzle in the cultural history of mid-nineteenth century India. That was the period of Renaissance in Bengal and new literary forms and visions were emerging. Foremost amongst them was Michael Madhusudan Dutt. Meghnath Badha was published in 1851, which was also the period of zenith of Ghalib’s poetry. Yet Michael was not alone. He was the product of an intellectual churning which can be said to have begun with Raja Rammohan Roy and which continued until Rabindranath Tagore and Jibanananda Das.

Most of the writers in Bengal had an English education. Many of them were erudite and had thorough familiarity with the full extent of western thought. But Ghalib had no such advantage. All the education he received was in Persian, so much so that at one time he aspired to be known as a writer in Persian.

In medieval thought, Man is of no consequence. He is either in the thrall of God or his beloved, and his free will has no part. Exercising free will was tantamount to Sin. The position was the same in the Muslim world. In fact the very name of Islam presupposes surrender. With the Renaissance, the western world rebelled against it. Rebels like Greco-Roman Prometheus and Judeo-Christian Lucifer appeared in the heroic mould. But there was no such movement in the world of Islam; perhaps it was impossible as Islam was a relatively young religion.

Here lies the wonder that was Asadullah Khan Ghalib, a product of the Islamic environment and without any exposure to western liberal tradition, who set free man from being a slave to both God and beloved. The contemporary Hindu tradition differed only marginally, if at all. A large number of Muslim names start with Abd or Ghulam, and an equally large number of Hindu names end with Das, both meaning slave.

The implication is very clear.

Into this milieu steps Ghalib, declaring, “The eyes of Saqi hold no mystery for me. Nor I am keen to have my cup filled. In my mehfil, I am waiting to travel the limitless sky.” He is not afraid of pain and frustration. He looks upon them as a challenge.

“Shikwa o Shukur ko Samar, Bima o Ummaeed ka Sanagh

Khanah e Agahi Kharab, Dil na Sanagh, Bala Sanagh”

(Complaints and thanksgiving are the fruits of despair and hope. The house of understanding, or the brain and the heart, is the only source of problems.)

He asks, why are you proud of your submission to God? All your arrangements for prayer and the result of prayer are contemptible.

He wants a wider universe. He is totally dissatisfied with the limits of his intellect and personality. In this he challenges his maker (God).

“Where is the next step of my desire? The world of possibilities appears to me only to be a footprint and not the reality which it is possible to reach.”

In course of time he comes to terms with God, but on his own terms. “After all, if all creation is You, then so am I. To give a cover of submission to my statements is only pride. The head bowing before you is your head and that head is bowing to you alone.”

Yet he is puzzled, and asks, “If nothing except you is present, then what is the continuous trouble in the world?”

Such a person will be last to be in thrall of that cruel beauty: the beloved. He is certainly not ready to voice the opinion of the earlier Titan, Mir Taqi Mir, who said, “It is unfair to attribute the freedom of action to helpless people like me. You did what you wanted and only to put the blame on me for no rhyme or reason.”

Whereas Ghalib asks, “What is devotion and where is love? If life means breaking one’s head on stone, has that stone necessarily to be one of the steps of your house?”

Even in the madness of his love, he transcends the limits of time and space:

“I cannot see anything in the exaltation of love, Asad. All the deserts of the world appear to me as only a handful of dust.”

“My place of worship is beyond the frontiers of intellect. People with vision say the Kiblah is only a representation of the real Kiblah.”

(Kiblah: the sacred object of Mecca.)

It was possible for Michael Madhusudan to portray Ravana as his hero, and in the long poems regarding his heroines to state the case of the normally condemned Kaikeyi or Surpanakha. He had the backing of Homer, Virgil and Milton. But Ghalib did not have access to such a tradition. Ghalib could not do what Michael could. He could not introduce new forms or techniques like free verse or the sonnet, because he had neither the knowledge nor access to that tradition.

Yet Ghalib does not need a Hero or Heroine. He does not attribute his ideas to some other person. He speaks them himself and is even ready to cut a joke with the Almighty.

“Why not join together heaven and hell O Lord

At least we will get a little more space to move about.”

Naturally such a person will be unforgiving towards all kinds of sham. He evolved a style and set a tradition which blossomed again in Iqbal, and is the soul of Urdu literature.

How can one evaluate Ghalib better than in his own words:

“The vision which cannot conceive the river in a drop and the whole in a part;

Is not the vision of one blessed with insight. It is only child’s play.”