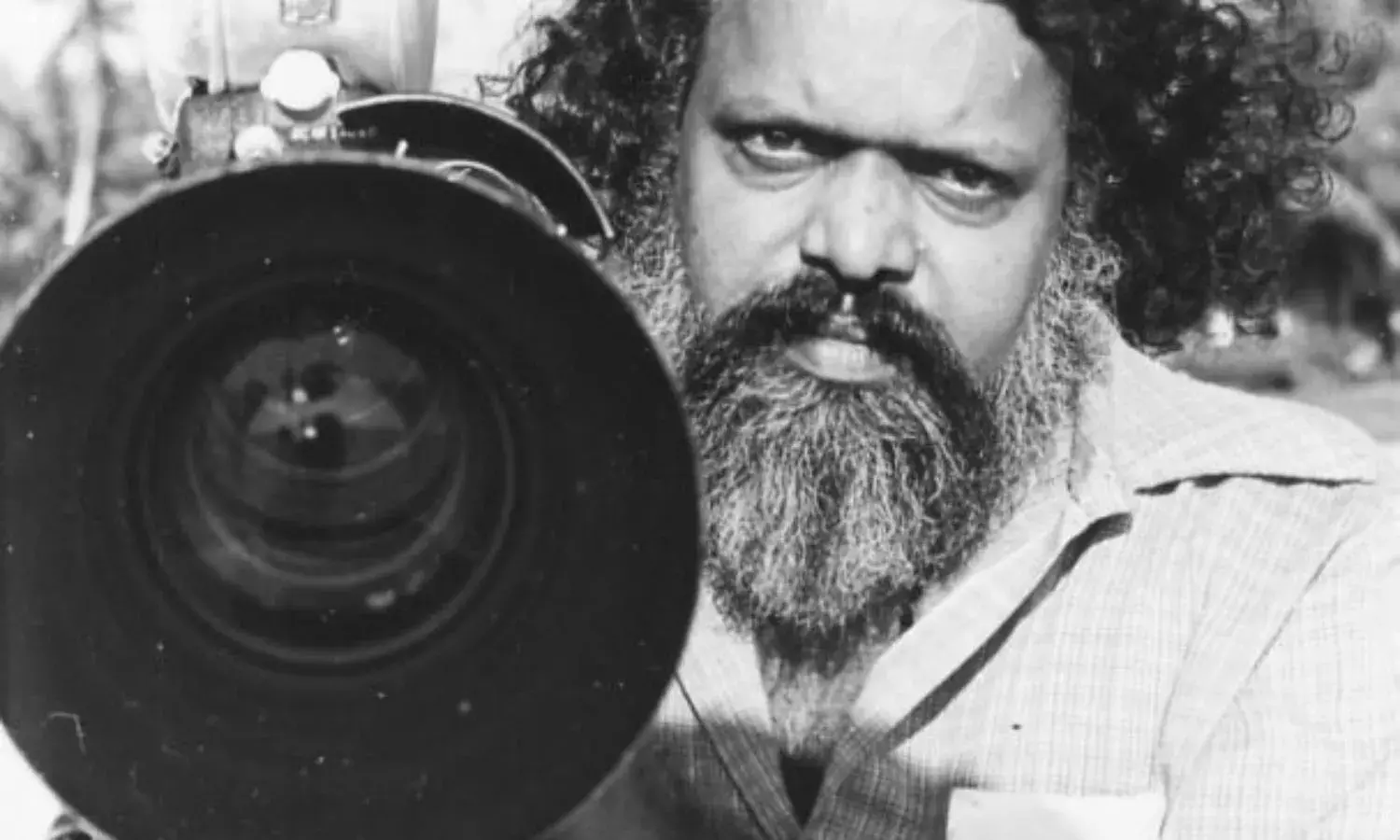

Remembering Aravindan…

Who left us at the height of his creativity

Twenty-eight years ago, when he was just 55 years old, the eminent filmmaker G Aravindan abandoned us with a suddenness and inevitability that left his worldwide followers stunned and saddened. A late-night heart attack took him away on March 15, 1991

Aravindan was at the height of his creativity, admired and applauded for the vibrant, ironic, at times, elliptical depiction of life’s many realities. He had made 10 feature films, five documentaries, two shorts and a TV film. With his first feature film ‘Uttarayanam’ (Throne of Capricorn, 1975), his work reverberated through far-flung festivals. Every new film from the director was markedly different and unexpected in its style and content. He was a poet, painter, writer, cartoonist, musician, singer, percussionist et al, all of which enlivened his films. He was adept at making documentaries as well as fiction films. I recall Aravindan as being shy, neither talkative nor affable, but his cherubic presence was lit with a warm smile and an awkward tilt of the head, while being feted at festival spaces. He was comfortable, vocal and even vociferous in his own language, Malayalam. When addressing in English, his questioning, expressive eyes would give away his initial reactions. In informal, close surroundings, disarmed by the soothing effect of some downer or another, he would sing aloud with abandon.

Aravindan and Uma at Vancouver

Copyright: Uma da Cunha

I recall the heavyweight Aravindan in Vancouver, striding on a swaying rope bridge high above a roaring, gushing river below – unperturbed – while I stood frozen, until he pulled me in. I only managed that terrifying stunt at his constant urging, and at which I shudder to this day. After that, I followed him blindly. I also recall a cold, wintry night after a late screening at the Berlin International Film Festival. He looked at me mournfully, his deer-like oval eyes filled with longing; “If only I could get fish curry and rice. Any chance, Uma?”. That’s Aravindan, ever hopeful of the impossible.

------

Excerpts from an article in the Financial Express, April 18th, 1982

‘Pokkuveyil’ - Surprise Award winner

By Uma da Cunha

Copyright: Uma da Cunha

ARAVINDAN'S latest Malayalam film ‘Pokkuveyil’ (Twilight, 1982) has been adjudged the Second Best Feature Film in the 29th National Film Awards. This particular film winning a top award has surprised many, including, one hears, the director himself. At the Filmotsav '82 Festival held in Calcutta, the crowds were visibly restless while this film was screened. The reason for the surprise is that ‘Pokkuveyil’ is a difficult film. In technique, style and subject matter, it is a film meant for a highly subjective audience.

Aravindan now has a staunch following of his own, here and abroad. He has proved himself a master of the cinematic medium without even having studied it. Part of his success with the medium is that he treats it as an experimental art form, almost as if he is deriving an intellectual satisfaction while playing around with it as imaginatively as he chooses to. There is no formalism or academics to his use of the cinema. That is why his films differ dramatically, one to the other.

Aravindan’s first film ‘Uttaranyam’ (Throne of Capricorn, 1974) used a straightforward narrative style. It dwelt on unemployed graduates and their dejection as seen against the backdrop of the freedom fighters of the previous generation. In ‘Kanchana Sita’ (Golden Sita, 1977), made in colour, Aravindan showed his innovative and daringly original approach to cinema. The film deals with the Rama and Lakshmana theme ending on the episode that brings Rama and his twin sons together. Highly stylised, it shows the spirit of Sita as the elements of Nature surrounding mankind.

‘Thampu’ (The Circus Tent, 1978) in black-and-white, is perhaps Aravindan’s most widely admired film. It traces the vanishing tribe of a travelling circus, concentrating on one such group. It shows, in telling and graphic detail, the saddened, isolated, vagrant life of circus artists and their inbred dependence. Touching sequences are those concerning two midgets and a wizened elder woman training a little child to follow in her dubious footsteps.

Aravindan’s ‘Kummaty’ (The Bogeyman, 1978), in vivid colour, is a strange fairy-tale story of a wandering old magician who is able to change children into creatures. He turns one boy into a mongrel and forgets to reverse the process. The mongrel has a hard time finding a place for itself, until his human parents realise what has happened. It takes a chance visit from the old magician to restore the boy. The music in the film is based on Kerala folk songs, mostly nonsense-ditties composed for children.

‘Esthappan’ (the name Stephen) was made in 1979, again using colour with the distinctive style that Aravindan has evolved almost in the manner of a painter. This film is about a prophetic, solitary fisherman whom the locals see as either mad or as a spiritual leader. The film dwells on local beliefs and superstitions, introducing foreigners with whom the protagonist has a special friendship.

Aravindan is an accomplished musician and singer in his own right, having trained in Hindustani classical music as well as Carnatic. He has scored the music of VK Pavithran’s Malayalam film, ‘Yaro Oral’. His use of incidental music in his own films is again most unusual and original.

For ‘Pokkuveyil’, Aravindan recorded the entire music at one sitting prior to the shooting of the film. If I am not mistaken, he scripted and edited the film according to the music. ‘Pokkuveyil’s music is, therefore, its single most cohesive and important factor. The music is Hindustani classic, using three instruments, with Hariprasad Chaurasia on flute, Raju Taranath on sarod and Latif Ahmed on tabla.

‘Pokkuveyil’ deals with a recurring theme today, the alienation of teenagers from their inherited culture because of a new life style to the point of causing a mental breakdown. Balu, the young man in this film, is an apathetic student. His mother leaves him in a hospital for psychiatric care.

Actor Balachandran Chullikkad in 'Pokkuveyil'

Credit: National Film Archive

In flashbacks we learn of the boy’s hero-worship for a fellow-student, a strapping champion athlete who becomes crippled due to an accident. The change in his friend is a shock and a setback for Balu. Another friend is a political activist who, unlike Balu, is set in his thinking and his goals in life. This friend too goes away to work as an underground agent. A young girl befriends Balu and is his constant companion. They both share a love for music and poetry. She too leaves because her father is transferred. When Balu’s father dies of a heart attack, he finds he is unable to communicate with his mother. Balu begins to lose his sense of balance and gives way to a fear neurosis. He withdraws into a mental condition of non-reaction, weariness and occasionally, dread and persecution.

‘Pokkuveyil’ blends landscape, seascape and music, to convert the shades and moods of Balu’s mind and his deteriorating mental condition. The sea is filmed in a surging, foreboding way, often so close to the eye to seem that it is bordering on one's own sanity. The harsh rock formations and the snakelike sand patterns convey suggestions of personal threat and danger.

Altogether, the film has a tempo and a rhythm that is novel enough to appear extreme and untenable in a mass media such as the cinema. That’s why it is a welcome surprise that a film using such unusual aesthetics as ‘Pokkuveyil’ should get the Rajat Kamal award “for its moving visualisation of the agony of the mind of a man dangerously on the edge of insanity.”