Life And Love Of Sufis

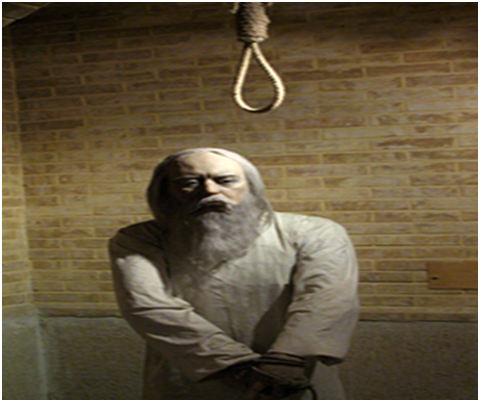

Mansur Hallaj: Sufis drew a lesson from his execution

gaah sufi gah qalandar chist

chun qalandar shawi qalandar baash

(Sometimes a Sufi, sometimes a Qalandar, what is this?

If you are becoming a Qalandar, remain a Qalandar!)

Like everyone else, medieval Indian Sufis also struggled with questions of identity and some of the big names chose to defy easy classifications. Sufis were organized into chains of lineages or silsilas – Chishti/Suhrawardi/Firdausi/Shattari/Qadiri/Naqshbandi – to name just a few, with distinguishing markers and traditions of each of them, which often tended to converge, besides the bigger and more dominating orders occasionally subsuming smaller and weaker ones; alternatively, smaller sub-branches moving on their own trajectories away from the main lineages, so Chishti-Nizami and Chishti-Sabiri, for instance.

As a lesson from the execution of Mansur Hallaj for claiming he epitomized the truth, or truth personified (anal haqq), and only a loud-mouthed person could make such claims in public, Sufis needed to steer clear of the political wrangling; and, some historians have shown Hallaj was killed for backing a wrong candidate for the caliph; his utterances were only used as a pretext. Therefore, the sane advice to the Sufis was to keep their mystical practices and spiritual experiences to themselves as personal secrets, but they would often spill the beans, as it were, or kashf-ul-asrar (revelation of the secrets) as they would like to put it.

Further, Sufis cannot be easily boxed into sectarian and political Shia/Sunni binary, nor can they be trapped in narrower and juristical Hanafi/Shafi’i struggle. And, the sharp line between shari’at (Islamic law) and tariqat (mystical path) cannot be sustained beyond a point either, for Sufis considered tariqat as the soul of the body called shari’at; or, as Delhi’s foremost Sufi, Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya, put it, shari’at cannot be abandoned altogether, because if you fall from tariqat, you fall into shari’at, and if you fall from shari’at, where will you go, except in the burning cauldrons of Hell?

Some of the leading Sufis were first rate ulama (plural of alim) to start with and they struggled to maintain a balance between the path of the shari’at, of strict conformity to the principles of Islam as interpreted by the jurists, and of tariqat, lost in love for God as generations of mystically inclined fine souls did. Thus, while some Chishtis were misunderstood as deviating too much from the straight path of Islam, some Naqshbandis were accused of acting less as broad-minded Sufis and more as champions of orthodoxy and fanaticism.

Following the mystic path, Sufis were supposed to have renounced the world in their love for God, but they were expected to live with the people and endure difficulties caused by them, not running away to lead a lonely life of an ascetic. As Hazrat Nizamuddin put it, Sufism is not about wearing a langota, or a loin-cloth, and running away to meditate in the jungle. But the ambiguity will remain, as for example, marriage is a recommended practice in Islam, but many of Sufis would remain bachelor, mujarrad, for they believed responsibilities of a married life come in the way of love and devotion to God.

Despite the occasional rise of extraordinary figures like Rabiya Basri, Sufism is supposed to be an exercise in manliness, or mardangi, sacrificing everything as a mad Majnun would do for his lovely Laila, but then stark male/female distinction would often be defied by some Sufis with homo-erotic orientation. Also, Sufis tended to avoid the company of women to generally keep clear of any khatra (danger) or tuhmat (accusation of sexual misdemeanor from the point of view of patriarchy of the khap variety), but they would sometime get involved in somewhat embarrassing associations with clean-shaven and fun-loving Qalandar boys, perhaps queered!

As the Sufis would like to put it, the ma’mla (transaction or relation) between Sufis and God and between Sufis and His creations are personal to them, and it is inappropriate to accuse the Sufis of indulging in any inappropriate activities; they were accountable to God for their actions, they feared and loved Him, and they were preparing all the time to submit to His judgment. Why create difficulties for people devoted to the love of God?