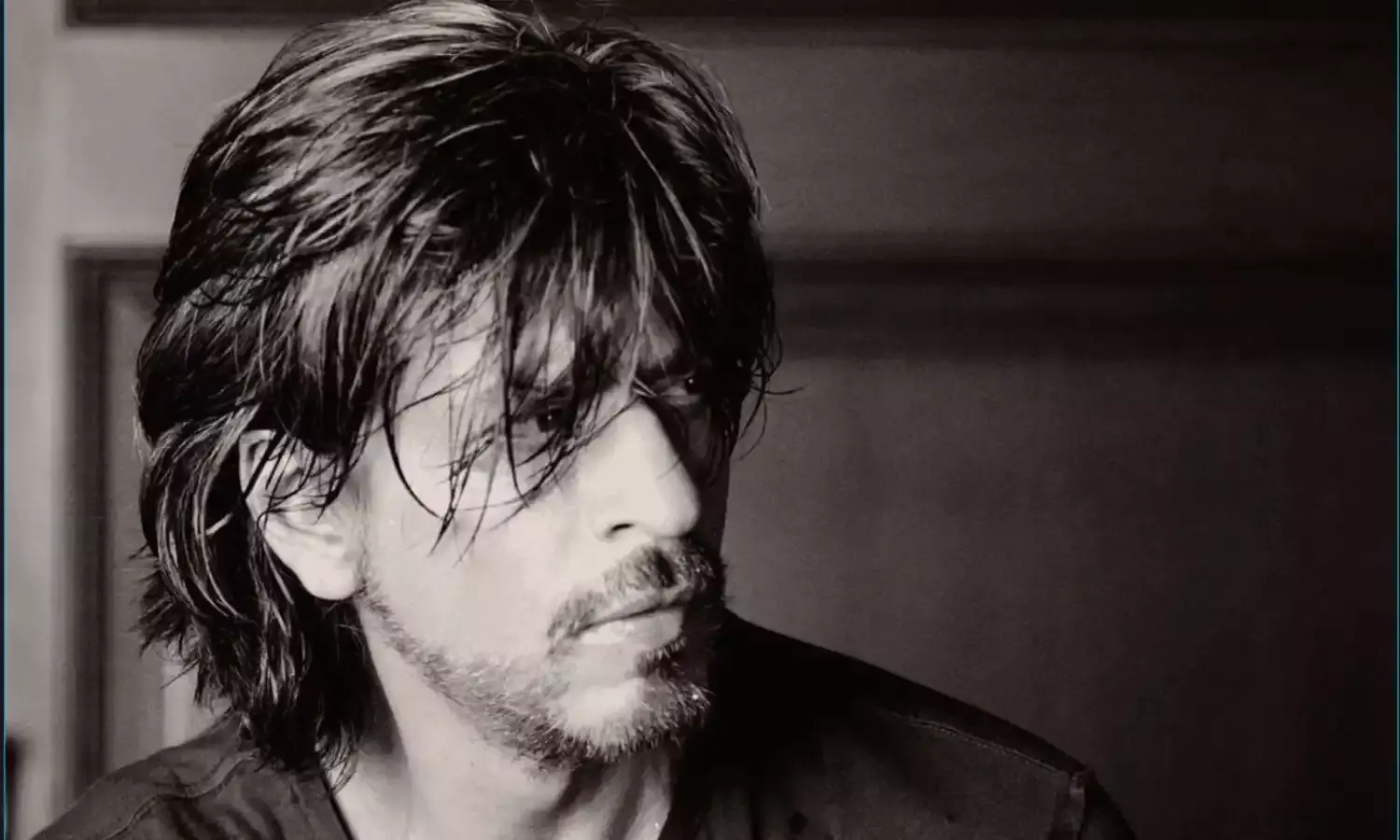

Death Threats To Shah Rukh Khan

Bollywood’s gig grossers have always attracted gangsters attention

With superstar Shah Rukh Khan getting Y+ security cover from the Maharashtra police following death threats from gangsters, the link between Mumbai’s film personalities and the city’s underworld has come to the fore again.

Gangsters’ infiltration into the Mumbai film industry began in a way with Haji Mastan, the city’s notorious don, between the 1960s and the early 1980s. It became noticeable in the 1990s with the opening up of the Indian economy, and with big money flowing into film production.

The city mafia, with ready money and no scruples, gate-crashed into the film industry. Mumbai’s gangsters are extortionists as well as financiers, often forcing producers and popular stars to accept their proposals.

In his paper on the relations between gangsters and Bollywood, Dr. Gary K. Busch of the University of Hawaii quotes Director Mahesh Bhat as saying: “There's hardly anybody in the film industry who has not been contacted by the mafia.”

Actor Sanjay Dutt was released from prison after completing a five-year jail sentence for possessing illicit weapons supplied to him by the architects of the deadly 1993 Mumbai terror attacks, points out Ronak D.Desai of the Lakshmi Mittal South Asia Institute at Harvard University in his article in Forbes entitled ‘Bollywood's Affair With The Indian Mafia (March 3, 2016)’.

In January 2001, Director Rakesh Roshan faced an assassination attempt and was given police protection thereafter. So were his son actor Hrithik Roshan, and director Karan Johar.

The ‘job’ to kill Rakesh Roshan was allegedly assigned by an Indian underworld figure based in Dubai, and financed with money laundered through Abu Dhabi, planned in Pakistan and ultimately carried out in India, Desai says.

But despite the violence, Bollywood stars would openly flaunt their “organised crime connections, and its A-list celebrities would routinely attend lavish, and well-publicised mafia parties around the world”, he adds.

Some producers even worked with gangsters to advance the latter’s interests. According to Desai, in 2001, Nazim Rizvi, producer of ‘Chori Chori Chupke Chupke’, and his assistant were sentenced to six years in prison for working with the underworld to extort money from the film fraternity.

However, the fact is that these links have proven deadly for the industry’s most notable members. “India’s most powerful underworld bosses like Dawood Ibrahim and Abu Salem would celebrate with Bollywood’s most distinguished members one day, they will extort them the next,” Desai points out.

According to Dr. Busch, the mafia-Bollywood link owes its origin to a misguided government policy on prohibition in the early years of independence. Don Haji Mastan’s entry into filmdom was facilitated by the denial of bank lending for film production at that time. It was only in 2000 that the law was changed to allow bank credit.

Prior to that film producers, directors and actors were forced to find alternate revenue streams to make their movies, “often from suspicious sources with strong links to criminal organisations,” Busch recalls.

But even when bank credit became available, the money was not enough to finance blockbusters. The mafia stepped in to fill the breach. A cosy and symbiotic relationship between the Mumbai mafia and Bollywood developed.

However, in many instances, filmmakers and celebrities were forced to accept underworld financing whether they wanted to or not, Dr. Busch points out.

Extorting money from Bollywood’s cinema elite is among the most profitable activities for the underworld. The profits would have jumped in recent years when big grosser productions became the order of the day.

Significantly, Shah Rukh Khan said in his police complaint that he had been getting death threats ever since the big financial success of his recent films ‘Pathaan’ and ‘Jawan’.

Though stars like Shah Rukh and Salman Khan are getting Y+ security, the law generally appears to be blind to the extortion racket in Bollywood.

“It is rare for prosecutions to target high-level crime figures or move beyond these perfunctory charges, especially in light of how ubiquitous Indian organised crime is within Bollywood,” Desai says.

“With certain minor exceptions, there has been virtually no legal response to organised crime’s infiltration of India’s film industry. While low-level gangsters are occasionally charged with single counts of extortion, racketeering or intimidation, it is rare for prosecutions to target high-level crime figures or move beyond these perfunctory charges, especially in light of how ubiquitous Indian organised crime is within Bollywood,” he points out.

After the liberalisation of the Indian economy in the 1990s, the mafia found that traditional forms of criminality did not have much place and that money could be made by a combination of criminal and legitimate activity. Extortion, threats, contract killings, smuggling and money laundering could be done along with conducting legitimate business. Moreover, this combination ensured money as well as social status.

Dawood Ibrahim’s ‘D-Company’ for example, indulged in all kinds of crimes as well as legitimate businesses. According to Dr. Busch, D-Company’s tasks were divided among Dawood’s brothers: Anees looked after smuggling, drugs and contract killings; Noora looked after film financing and extortion from film personalities. Iqbal, a low-profile person, looked after his legitimate business activities including share markets in Hong Kong and jewellery and gold businesses.

The ever-ambitious film industry also needed a lot of money, and legitimate sources were hard to come by. The gangsters stepped into breach with alacrity, financing even “unfinanceable” ventures. Hence the growth of a symbiotic relationship between the mafia and glitzy film world honchos.

Though India has had professional criminals in its history like the “criminal tribes”, “thugs”, “dacoits” and urban “badmashes” organised, gangsterism of the Mumbai type began when, after independence in 1947, many States introduced prohibition.

As in the United States, gangsterism followed prohibition, to deal in illicit liquor. The socialist Indian economy marked by the licence-permit Raj, gave a boost to smuggling of a variety of goods.

Criminal gangs were co-opted by the parallel economy, and in time, these gangs got the upper hand in the parallel economy.

As elections became more and more expensive, candidates needed enormous amounts of money, which they collected informally from the capitalists (as political contributions were not legitimate in India) and also from the mafia.

And having taken the money from the mafia, politicians who control the State apparatus, would not let the police take action against them. This is the reason for the absence of any consistent action against Mumbai’s Bollywood-linked mafia.

With globalisation and improved communication, India-based gangsters, whether from Mumbai or Punjab, started operating from Asia and Canada also. India has also become a haven of smuggling, which is the backbone of the gangsters.

Here is what Dr.Busch has to say on smuggling in India: “India remains a major transit point for heroin from the Golden Triangle (Shan states) and Golden Crescent (Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan) en-route to Europe. India is also the world's largest legal grower of opium, and experts estimate that 5–10% of the legal opium is converted into illegal heroin and an additional 8–10% is consumed in high quantities as concentrated liquid.

“The pharmaceutical industry is also responsible for a lot of illegal production of mandrax, much of which is smuggled into South Africa. Diamond smuggling via South Africa is also a major criminal activity. In addition, a lot of money laundering takes place within the country and with the Middle East mostly through the use of the traditional hawala.”