Protecting India from Maritime Disasters

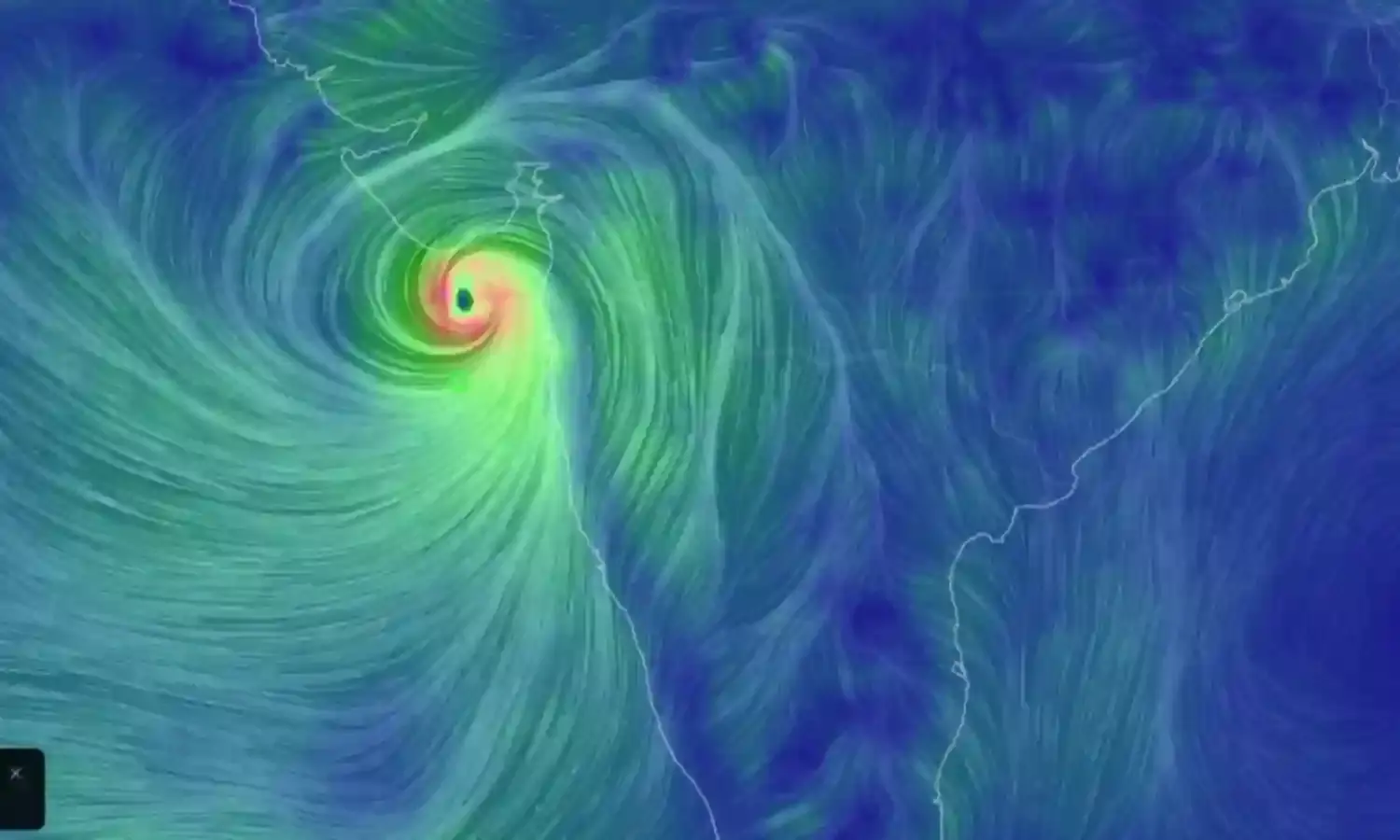

The Arabian Sea is also turning into a hotbed of cyclonic storms;

On 17 May, Cyclone Tauktae, the first from the Arabian Sea in over two decades, barrelled up the country’s western coast, making landfall in Gujarat. The cyclone hit the coast with such force that waves taller than three metres rose in the Arabian Sea, flooding thousands of villages along the coast, damaging many buildings. Strong winds uprooted trees and power poles, disrupting traffic and causing power outages.

The cyclone has caused severe damage in Kerala, Karnataka, Goa, Maharashtra, Gujarat and Daman and Diu. The airports in Kochi, Goa, Mumbai, Ahmedabad, Rajkot, Vadodara, and Kandla airports were cordoned off for security reasons. Vadodara airport remained closed all day and about 18 flights were cancelled in Ahmedabad. Ships were sent back to sea from ports along the way so they would not collide with each other in the strong winds.

This is the first time such a threat has been felt along India’s western coast. Over two lakh people living in the coastal areas of various states were evacuated due to early warning from the Indian Meteorological Department. These early warnings about the cyclone’s passage and speed are commendable, and saved millions of lives. Yet two dozen people lost their lives in the cyclone.

Tauktae is the first cyclonic storm to hit the Arabian Sea this year, that too in May, before the monsoon. According to the IMD there were an average of five cyclonic storms in the Indian Ocean each year from 1891-2017, four in the Bay of Bengal and only one in the Arabian Sea, where cyclonic storms were also less severe than in the Bay of Bengal. But in the last few years the number of cyclonic storms in the Arabian Sea has been increasing and the intensity of destruction caused by these storms is also increasing.

According to a study by the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology, the Arabian Sea is also turning into a hotbed of cyclonic storms, like the Bay of Bengal, as its surface temperature has risen by 1.2–1.4°C over the last 40 years.

Cyclones are still more common in the Bay of Bengal, where the sea surface temperature remains above 28°C through the year. The IMD found that when Tauktae passed through Goa, the sea surface temperature there was 30-31°C, increasing the speed of the cyclonic winds and causing more destruction. While cyclones have risen from the Arabian Sea for four years in a row, Tauktae turned into a fast-moving cyclone between May 14 and 16, unlike previous years.

The planet’s rising temperature is contributing to the rapid increase in a variety of natural disasters. A study by the University of Oregon found that the Indian Ocean is warming faster than other oceans. Another study by Daniel Levitt and Nico Camnada found that a 1°C increase in sea surface temperature increases the wind speed in a cyclone or hurricane by 5 percent. High-velocity cyclonic storms wreak havoc as we saw with Tauktae.

Heavy rains in Kerala before the cyclone caused severe flooding in many districts, severely damaging crops and buildings and killing two people, while eight people died in Karnataka. 73 villages in six districts of Karnataka were badly damaged by strong winds and heavy rains. In Goa, two people died, 200 houses collapsed and 500 trees were uprooted. Mumbai, a city 120 kilometres away from the path of Tauktae, was also badly affected by the strong winds and heavy rains. Further north, the strong and humid winds of the cyclone are affecting Rajasthan, Delhi, Punjab, Haryana and some other states in the form of unseasonal rains.

As the average temperature of the earth rises, so does the temperature of the oceans. According to a NOAA report, rising sea levels also increase the damage caused by natural disasters such as flooding, erosion, tsunamis. The Indian National Center for Ocean Information Service of Hyderabad finds that the sea level around India is rising at an average rate of 1.6–1.7 mm per year. Rising sea level not only causes natural disasters related to the sea but also affects people living near the coast.

About 40 per cent of India's people live in the coastal areas. The IMD reports that cyclones affected 320 million people in the country each year between 1980 and 2000. According to a 2014 report of the United Nations, 2.14 million people in India were displaced by natural disasters in 2013 alone, accounting for nearly 10% of the world's displaced people as the result of natural disasters.

Rising sea levels threaten 36 million Indians with flood-related hazards by 2050, a study in Nature estimates, and by century’s end that number could reach 44 million. As for ongoing effects, the Council on Energy, Environment, and Water found in December 2020 that 75 per cent of India's districts have been affected by natural disasters due to climate change. 258 districts out of 600 were affected by the onset of cyclones in the last decade. Since 2005, the number of districts affected by cyclones more than tripled and the intensity of disasters doubled as compared to 1970.

The startling rise in these unnatural disasters clearly highlights the fact that excessive tampering with nature is becoming the cause of our own destruction, and of many other species of beings.

The Covid pandemic is also a natural warning. It is still not known how the disease originated and what is the main cause of its occurrence. The incidence of epidemics caused by zoonotic viruses has grown, and this has been linked to deforestation and overexploitation by industrial agriculture. So, we must stop tampering with nature too much.

In view of the increasing number of natural calamities due to rising temperature, the Union and State governments should take care of natural resources to minimise the incidence of natural disasters. They need to keep cyclone and tsunami warning devices in place. In addition, the coastal states should assess the environmentally sensitive areas of each district in their state, and put in place safeguards to overcome natural calamity in each area.

Our governments should impose a complete ban on any kind of construction and development projects in the environmentally sensitive coastal areas. They should maintain the presence of natural wetlands, mangroves and other vegetation in the coastal areas, or renew them, as these help prevent and reduce the damage caused by maritime natural disasters.

The Union government should not relax construction rules in the coastal areas in favour of big private developers as it did in 2018 by relaxing rules under the 2011 Coastal Regulation Zone Notification, as this has made already environmentally sensitive coastal areas more prone to natural disasters.

We should remember that the development of any place should be for society, and should minimise the harm to other beings. If we do not remain alive then development will have no meaning. To save the coastal areas from natural disasters, our governments should adopt pro-people and nature-friendly models of development.

Dr Gurinder Kaur is Professor, Department of Geography, Punjabi University, Patiala